Brexit blamed as language assistant numbers dive

The number of modern-language assistants (MLAs) in Scotland has almost halved in a year, amid fears that Brexit has deterred European students from working in the UK.

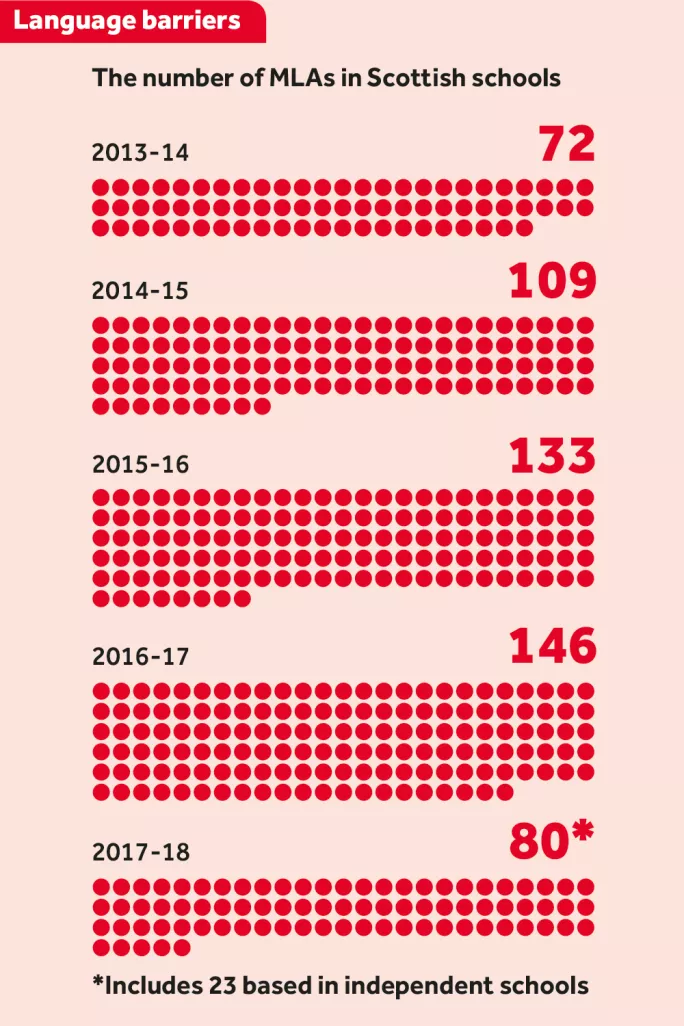

The British Council - which arranges for MLAs to work in the country - told Tes Scotland that 80 are being employed across 15 local authorities this year, down from 146 across 14 authorities last year. This is one of the lowest figures since current records began in 2003.

A low point of 72 MLAs was reached in 2013-14, as local budget cuts started to bite, but numbers revived as councils used funding from the Scottish government’s 1+2 languages programme to recruit MLAs at a cost of about £10,000 each per year. That progress appears to have gone into reverse, and now the highest figure recorded - 278 in 2005-06 - looks to be a distant prospect in light of fears that Brexit is driving away potential MLAs.

British Council Scotland’s head of education, Lucy Young, said the reduction in MLAs was “not entirely unexpected”, since many used 1+2 funding, which has reduced as the policy has been rolled out. She added that her organisation is “working with stakeholders to explore options for local authorities to diversify their funding for future MLAs and support their continued recruitment”.

‘Worrying situation’

Gillian Campbell-Thow, chair of the Scottish Association for Language Teaching, said many local authorities had made financially driven decisions not to take on MLAs this year, despite the “vitality of language” and the “lasting legacy beyond the nine-month stay” they offered. She added: “The worry with Brexit is that we won’t be able to provide our young people and teachers with the experiences that have been previously afforded.”

Ms Campbell-Thow described this as “a very worrying situation”, given the fraught political climate internationally, and with the UK’s exit from the European Union fast approaching. “Now more than ever we need our young people to be equipped and ready to engage in a globalised society,” she said. Reducing the number of MLAs would “have a significant impact on this”, and she called on the Scottish government to explore how to encourage more to come to Scotland.

In recent years, MLAs have spoken French, German, Italian, Spanish or Mandarin as their first language, with French more common than the other four languages put together.

John Edward, director of the Scottish Council of Independent Schools, said: “The substantial drop in language assistants is a worrying sign for Scotland and the UK in several ways [and] is ominous in light of the EU referendum result.”

Mr Edward, chief spokesman for Scotland Stronger in Europe during last year’s EU referendum, added: “Any uncertainty over the place of EU nationals in the UK was always going to destabilise some of those choosing to live and work here, and it does not augur well for the Scottish government’s rightly ambitious 1+2 languages policy. Scotland’s pupils, in a globalised world, need all the skills they can develop - foreign-language assistants deserve all the support they can get.”

Euan Duncan, professional officer for the Scottish Secondary Teachers’ Association, argued that Brexit had made Scotland “an unappetising destination” for MLAs. He said: “Many students considering whether to come here will be considering their wider opportunities for work at a later date. The massive uncertainty caused by faltering EU withdrawal negotiations must be a major factor in the reduction in the number of language assistants considering Scotland for placements.”

Mr Duncan fears Scottish pupils’ views of other countries might also be affected by the decline in MLAs. “The loss of opportunities to engage with first-language speakers from other countries will impoverish the learning experiences of young people and could lead to an ‘us and them’ way of thinking,” he said.

Aside from worries over Brexit, some commentators fear the potential impact on MLAs as local authorities look ahead to the end of an important revenue stream. Funding for the national 1+2 policy - under which pupils are expected to have knowledge of two languages other than their own before they reach secondary school - is expected to end by 2020.

The Scottish government said it provided the British Council with £195,000 a year to manage MLAs and that it would “continue to work with them to promote the scheme”.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters