Today, many schools will be marking International Women’s Day.

From teaching about overlooked women in history, or the female hidden figures in Stem, teachers will be familiar with using International Women’s Day to make women’s achievements more visible in the curriculum.

But how many are using International Women’s Day to challenge the sexual harassment and discrimination faced by teachers and pupils?

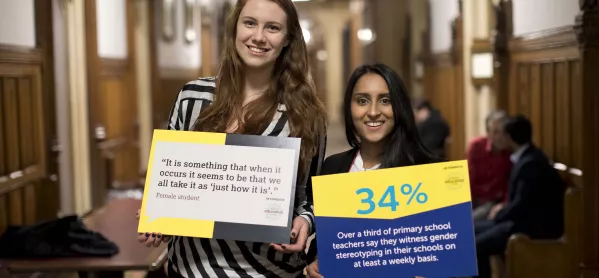

Research in 2017 by the National Education Union (NEU) and UK Feminista revealed that sexual harassment of female students is commonplace in schools.

- One-in-three teachers in secondary schools witness sexual harassment in their school on at least a weekly basis.

- Almost 20 per cent of primary school teachers have witnessed sexual harassment.

- 37 per cent of girls have experienced sexual harassment at school, compared to 6 per cent of boys.

And it’s not just the students who are dealing with sexual harassment. NEU research in 2018 revealed that 75 per cent of women teachers had experienced sexual harassment at work; 50 per cent reported inappropriate comments by staff and students and 30 per cent had experienced inappropriate gestures or physical expressions.

One said: “I have been whistled at while trying to teach, and one extreme case where a boy pushed his crotch up against my back to intimidate me. The boy was removed from my lesson once and then I was asked to accept him back in.”

What the law says

Sexual harassment is unwanted conduct of a sexual nature. Sex-based harassment is not necessarily sexual in nature but is related to the sex of the person being harassed.

Both are unlawful under the Equality Act 2010, which defines harassment as unwanted behaviour which violates someone’s dignity, or creates an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment for them.

Sexual harassment could include:

- indecent or suggestive sexual remarks, including “jokes from a colleague, student or parent;

- display of offensive sexual material or sexist graffiti;

- persistent unwanted physical touching.

A single incident could constitute harassment if it is sufficiently serious. A series of incidents is likely to amount to harassment, especially if a teacher has given a clear indication that the behaviour is unwanted.

All schools have a legal duty to take active steps to eliminate discrimination and harassment of girls, to advance equality of opportunity, and to foster good relations between girls and boys, rather than just deal with the fallout when discrimination and harassment happen.

Employers with more than 150 employees have the same duty in respect of their female and male staff.

What you can do?

If you’re experiencing sexual harassment, the first thing to do is to tell someone. Research by the Trades Union Congress has found that only one in five women who experience sexual harassment ever tell anyone about it.

In spite of the #MeToo movement, there is still a lot of shame, stigma and fear of negative professional fallout associated with speaking out.

- If you’re in a union, talk to your rep who can advise you accordingly. Your colleagues may have made similar complaints and you may be advised to tackle the issue with them collectively. If you don’t have a union rep, talk to a trusted colleague, your HR department, or your manager.

- If it feels safe to do so, ask for the behaviour to stop.

- Offensive and harmful student behaviour should be reported under the school’s student behaviour or discipline procedure or in writing to your headteacher or principal.

- Gather all the written evidence that you have; letters, emails, texts and relevant screenshots. Keep a diary of incidents of unwanted conduct including dates, times, places, the names of witnesses, and your response to the behaviour.

- Ask your union rep or school or college office for copies of harassment and bullying policies. All employers should adopt harassment and bullying policies with a clear definition of what sexual harassment is and procedures for dealing with it fairly and quickly. Talk to your union rep or your colleagues about asking your employer to adopt a sexual harassment policy if there isn’t already one in place.

What can school leaders do?

School leaders can change the culture in a school by rolling out training for all staff, encouraging staff to report harassment, and making sure that all reported incidents are treated seriously and acted on.

School leaders should also be aware that sexual harassment is a health and safety issue, as well as one of equality. Preventative steps could include inset days on sexual harassment, posters in the staffroom, making sure risk assessments identify harassment and violence risks, such as lone working and school trips.

School leaders also have a positive role to play in developing a curriculum that promotes equality and healthy relationships.

From September 2020, relationships, sex and health education will be statutory, including teaching youngpeople about important concepts such as consent and what is a healthy or abusive relationship.

Taking a whole-school approach to talking about sexism, including challenging gender stereotypes and ensuring that women and girls are visible in the curriculum, is vital for preventing harmful and discriminatory behaviours developing early on.

Sandra Bennett is legal officer at the NEU

Find out more about how you can mark International Women’s Day