It’s time to re-think the physical structure of the classroom

The blackboard may have been replaced by an interactive whiteboard, but classrooms today still look pretty similar to those of fifty years ago - rows of desks facing a teacher, filled with students anticipating instruction.

And so, while the world has changed around us with advances in technology and digitalisation, it seems education, learning and the classroom itself remain stuck in the past.

Learning is not a spectator sport

Yet there’s an opportunity -indeed a necssity- to optimise learning by rethinking the physical structure of the classroom. As authors A.W. Chickering and E. F. Gamson say in Seven Principles for Good Practice in Undergraduate Education, “Learning is not a spectator sport…[Students] must talk about what they are learning, write about it, relate it to past experiences, apply it to their daily lives. They must make what they learn part of themselves.” That is, students must be active participants in learning.

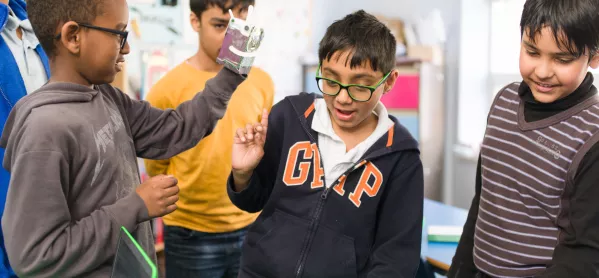

We need to shift teaching and learning away from instructionism, where the core activity of the classroom is instruction by the teacher. The best learning often takes place when students can experience a topic, when they have a chance to apply it to real life situations and contexts, when they can try it out, collaborate, and share. Students can’t do any of these things when they’re sitting in silence three feet away from each other.

The physical structure of a large proportion of today’s classrooms don’t easily allow for a constructivist approach to teaching, where students learn by making, doing, or building something. Educators (and employers) the world over recognise the need for creativity, but true creativity isn’t going to happen when students are sitting behind desks trying to absorb information for 45 minutes..

Most classrooms seem set up to facilitate training students to memorise and regurgitate information according to core standards, standards which are out of the hands of those who really ‘own’ education - the teachers and students. This assembly-line standardisation of teaching mimics an industrial process which has no place in the nurturing of young minds.

To quote Graham Brown-Martin, author of Learning {Re}imagined and chief education and product officer at pi-top: “Constructionism…relies on abundance and discovery where knowledge is constructed by making things and sharing them. Students use information they already know to acquire more knowledge. It is distinctly collaborative and social in nature.”

The classroom as a space for learning by making

Learning by making has many benefits; students learn skills they need for the future such as collaborative problem-solving and critical thinking. It engages different types of learners of all abilities, meaningful feedback can be given within a lesson, students retain knowledge effectively, and most of all, it’s fun.

Mitchel Resnick, professor of learning research at MIT MediaLab, uses real world examples in his essay about playful learning to show how many of the best learning experiences come when students are working on something that they enjoy and care about. Rather than forcing a joy of learning on the unwilling, Resnick describes how students with short attention spans in a traditional classroom often show serious depths of concentration when engaged in projects that really interest them. It doesn’t matter how hard the activity is, as long as it connects with the student’s interests.

The physical space and the emotional mind

The physical classroom needs to change to accommodate and support playful learning by making, and needs to be redesigned to optimise student engagement, maintain focus and make them feel comfortable.

“Feeling comfortable” may sound twee, but the physical space can affect student morale, engagement and in the end, their ability to learn. If a space is welcoming and relaxed, and has minimal distractions, it enables students to focus on the topic in hand.

A study by the University of Salford on how the design of primary school classrooms affects children’s academic performance suggests that a well-designed primary school boosts reading, writing and maths skills. Indeed, the study estimates that the impact of moving an ‘average’ child from the least effective to the most effective space would be around 1.3 sub-levels, a meaningful improvement when students typically make two sub-levels of progress per year.

The report also found three further influential factors on learning impact; naturalness (light, temperature, air quality); individualisation (ownership and flexibility of the space); and stimulation (complexity and colour). So what effect can we understand poor classroom design to have on pupils?

So what does the ideal classroom look like?

According to a report by Herman Miller: “The goal of classroom design is to enrich academic, psychological and sociological growth. The design of such spaces should…avoid prescriptive and restrictive behaviours, for both teachers and students. The design of learning spaces should increase levels of engagement, foster active learning and teaching, and support the learning goals of higher education institutions.”

The physical classroom should be used to support, not restrict, active teaching and learning by making; an environment in which students can thrive, learning the skills they need to take on a future we aren’t certain of.

Find out how pi-top teaches students how to take on life’s challenges, collaborate, problem-solve, think critically, be creative and to learn how to learn.