How tech can bring real-world conservation to schools

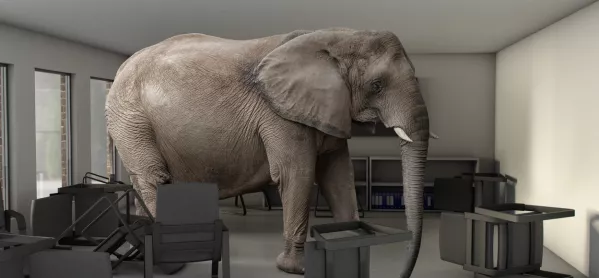

Earlier this year in rural Kenya, herds of elephants were spotted roaming, providing a potential source of danger to thousands of children making their way to school. The solution? WhatsApp.

The app is used by community scouts to track the herds and share timely updates, and, in this case, allowed that information to be shared quickly with members of the local community. Students were then advised on safer routes to and from school.

“SORALO (the South Rift Association of Landowners) has been using WhatsApp as the linchpin of its communication systems for the last two years,” says head of conserving co-existence Guy Western.

“It’s multifunctional, from allowing our community scout teams to communicate across an area roughly the size of Wales, to sharing locations and photos of wildlife, and recording incidents of human-wildlife conflict.”

WhatsApp has been used by local teachers to boost knowledge and awareness of conservation among students, too. They’ve been sharing curriculum ideas for a local wildlife club and have set up face-to-face training on conservation at an education centre, says head of educational outreach Joel Njonjo.

Bringing conservation to life

All of which the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), working alongside SORALO, African People and Wildlife and local communities as part of its Land for Life project, hopes serves as inspiration for UK teachers looking for ways to use technology to bring conservation to life in their own classroom.

More and more teachers are actively seeking out ways to embed sustainability, conservation and biodiversity into the curriculum, says WWF UK’s education manager, Matt Larsen-Daw, and there are a growing number of tools out there that they can access.

Just as WhatsApp is being used as part of WWF’s Land for Life project in Kenya to monitor wildlife, UK students can download the Seek app, developed by WWF in partnership with citizen science platform iNaturalist, to monitor the biodiversity in their own backyard. Launched in 2019, the app uses image recognition technology to let students identify and monitor a wide array of plants and animals in their local area.

“While they may not have elephants traipsing across the landscape or prides of big cats that need monitoring and protecting, they will see when native ladybirds begin to disappear from their gardens or when a new kind of bug moves in,” says Larsen-Daw.

It’s a great starting point for teachers looking to integrate conservation into the classroom, he adds, as it’s simple to use, ideal for independent learning and gives students the opportunity to immerse themselves in the natural world. Plus, it doesn’t require teachers to swot up on local wildlife beforehand.

“It jumps right over the need for teachers to feel they need to have an in-depth knowledge, as the app provides that,” he says. “Students can gain a raft of different skills, including an understanding of what scientists and conservationists do in the field, while having a strong and enriching educational experience.

“After all, no matter how high the quality of the video [that students watch in class], it’s not quite the same as discovering something for the first time hiding under a leaf in your garden.”

Multimedia approaches in schools

And once students are suitably enthralled by the outdoors, there are a raft of multimedia resources created by the NGO that teachers can then access to take the conversation into the classroom, too.

These include support materials linked to WWF’s Land for Life project in Kenya and Tanzania, which is focused on finding and funding community-led solutions to help wildlife and local communities co-exist.

There’s also the youth-friendly version of the WWF’s latest Living Planet report, a biennial index on global conservation and biodiversity, available with a teacher’s pack that offers suggestions on how to integrate the study into various topics.

Students could explore how the data is gathered and interpreted as part of the maths curriculum, suggests Larsen-Daw, or use it as the basis for understanding the interconnections within the living world as part of natural sciences.

“It takes real-world examples and looks at what’s happening right now, what are the changes and why are they happening,” he continues. “It’s a powerful way to bring those concepts to life.”

Our interconnectedness

Then there are the companion resources to the 2019 Netflix series Our Planet (which is also free to watch on YouTube), exploring the interconnectedness of species all around the world. Teachers can simply head to ourplanet.com to access an array of educational resources, from bite-sized videos designed to slot into a single lesson, to materials for exercises, projects and class discussions.

One of the most empowering for students is the Future Visions film, Larsen-Daw explains, which uses footage from the series, overlaid with CGI, to create an “imagined reality” where climate change and conservation are no longer a problem.

“The problem we find, particularly when working with young people, is that there’s a huge amount of information, some of it very scary, about the state of our world,” he says. “That can be frightening and a bit disempowering. If we want young people to feel inspired to pursue a career or to take action for the environment in their own lives, they need to feel it’s worth fighting for.”

And this sense of connection - be it between different living systems or communities as far apart as Kenya and the UK - should be at the crux of all efforts to inform and engage students on conservation, he adds.

Perhaps one day soon these same tools could even be used to connect students from around the world in their fight to protect wildlife, suggests Western. “With the power of WhatsApp and Zoom, schoolchildren in Kenya, the UK and across the world could be sharing experiences and conservation stories, learning and inspiring each other to go on to achieve bigger and better things. Watch this space.”

Tes is a media partner of WWF’s Land for Life appeal, which aims to help improve the livelihoods of more than 27,000 Maasai people in southern Kenya and northern Tanzania. Through the Land for Life project, WWF is collaborating with local communities and partners to develop solutions for people and wildlife to coexist and thrive in Kenya and Tanzania. If people give a donation to the appeal before 2 February 2021, the UK government will match all public donations, up to £2 million. Donate at wwf.org.uk/life