Lessons in taking action: how to use the Living Planet Report with students

Awareness about human overconsumption and its disastrous effects on the environment is growing, with widespread coverage in the news, on TV and across social media. The latest Living Planet Report from WWF grabbed the headlines with its shocking statistics: only a quarter of the planet’s land is now free from the impact of human activity and there has been a fall of 60 per cent in global wildlife population sizes since 1970. South and Central America have suffered the steepest drop (89 per cent), and, as WWF reported in 2013, the UK has seen 56 per cent of its species decline in the past four decades.

The report makes it abundantly clear that this should be a concern for all of us. It concludes that we’re the first generation to truly understand nature’s value to humanity and our impact upon it and that we’re the last generation that can reverse the damage. It makes for sobering reading, but, coupled with the youth version of the report it also offers valuable learning opportunities for students. Here are some ideas for exploring the report in class:

Why does biodiversity matter?

If we’re going to inspire young people to protect nature, we need them to understand why it’s vital to do so. Help them to build their connection with the natural environment with a visit to a nearby nature reserve or woodland, or even by exploring the area around the school. You could see how many bird, mammal and invertebrate species they can spot and identify, familiarising them with wildlife and starting the conservation conversation. The natural environment can also be a great source of inspiration for art.

The report highlights issues such as rainforest destruction and plastic pollution in the oceans; it estimates that 90 per cent of seabirds now have fragments of plastic in their stomachs, compared with 5 per cent in 1960. Students can sometimes feel disconnected from these far-away issues, so try using inspiring videos (such as the Planet Earth series) or images from National Geographic to help your classes connect. You can also use Google Expeditions to explore a huge variety of biomes including rainforests, oceans and coral reefs; these virtual reality field trips are a great way to create an emotional connection to distant places.

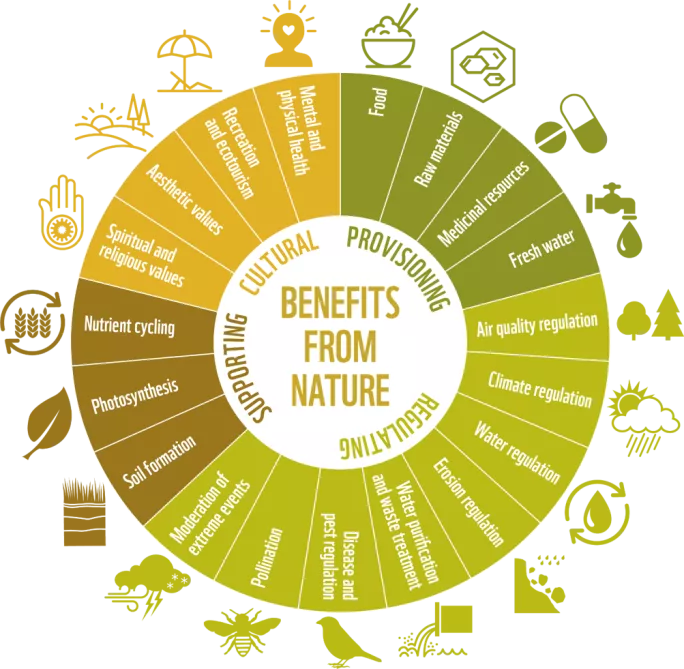

Once your students have been inspired by the majesty of nature, you can use the report to highlight how the environment interacts with humanity. There’s an excellent infographic (on page 18) that shows 19 benefits of nature; you could ask students to research them and report back to the class. They could, for example, look into the use of medicinal plants such as cinchona and sweet wormwood, which created the drugs quinine and artemisinins, both of which are used to fight malaria. Older students could explore the health and wellbeing benefits detailed in The Nature Fix by Florence Williams, where connection with nature is linked to lower inflammation, reduced anxiety and increased memory.

Creating complex food web diagrams is another great way of getting students to think of nature as an interconnected system. Ask questions such as “What will happen if the trees are destroyed?”, working through the food web to explore how vital they are for all life. This effect can also be modelled in the playground by getting students to form a food web, with each designated a named species. They can then find the links between them and connect them with string. Remove one element to allow them to see the effect (via the string) on the next part and realise the knock-on effects until it eventually reaches humans. This kind of systems thinking is vital for students to realise they are going to be affected by biodiversity loss if we don’t all act quickly.

The report also has a huge amount of socioeconomic and human development data presented in a series of graphs (pages 24 and 25). Students could use these to look at the links between a variety of data sets - such as international tourism and carbon dioxide levels, or population and tropical forest loss - enabling them to draw links between socioeconomic change and the loss of nature.

What are the threats to biodiversity?

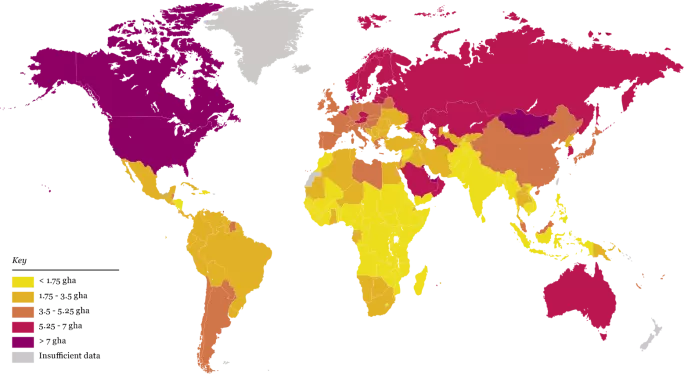

The next stage is to get students to understand the threats to the natural world and the way that they can, unintentionally, be part of the problem. The second chapter of the report summarises the threats to different systems through a series of infographics and maps that can be used to challenge students to think about and discuss issues such as overconsumption and over-cultivation (page 28). The report also contains an excellent choropleth map (page 33) that shows how consumption rates vary by country. The map can clearly be linked to GDP data and shows the rich-north/poor-south divide, offering an excellent prompt for analysing consumption trends and development.

Another extremely useful tool is WWF’s environmental footprint calculator, which allows individuals to work out their own ecological footprints. Students can work with a teacher or parent to fill out the survey and get a picture of the average footprint and compare their data against the UK and global averages.

How can we create the future we all want and need?

If we’re to reverse the trend in species loss highlighted in the report, we all need to take action, and you can be a part of that action with your students. You can teach your classes how to reduce food miles by growing and cooking seasonal produce, for example, and you can support nature in your school by growing more plants to attract bees and other pollinators. (Our school has gone a step further and has its own beehives on the roof, with students working alongside teachers to look after the bees and harvest honey).

You could also start a plastic-reduction group with students and teachers working to find ways of reducing single-use plastics (the group at our school has successfully removed single-use plastic cups and continues to find innovative ways to use less plastic). Students could also work with technology teachers to design and make habitats such as bug hotels or bird feeders. Teachers can also encourage students to take part in citizen science projects like the Big Butterfly Count or the RSPB Birdwatch, and they can write letters to local politicians to support local nature programmes. Teachers and leaders wanting to pursue sustainable education further can enrol on the free CPD course on education for sustainable development developed by the WWF.

Perhaps most importantly, teachers should encourage students to get outside and into nature as much as possible. It is only through teaching these lessons that we can get our young people to connect with nature, realise the risks that overconsumption presents to the world around us and be inspired to take action to reverse the decline of biodiversity, not only in far-away places, but in our own backyards.

Nic Ford is academic deputy head at Bolton School (Boys’ Division)