Introverts make up between a third and half of the population. According to Susan Cain, whose book Quiet: The Power of Introverts is an international best-seller, there is one key difference between this group and extroverts. “Introverts and extroverts differ in the level of outside stimulation that they need to function well,” she writes. “Introverts feel just right with less stimulation, as when they sip wine with a close friend, solve a crossword puzzle or read a book. Extroverts enjoy the extra bang that comes from activities like meeting new people, skiing slippery slopes and cranking up the stereo.”

Extroverts, therefore, derive energy from going out, socialising in groups and standing in the middle of a busy classroom. This can make them naturally suited to teaching: they draw energy from the constant activity and large-group interaction required during the school day.

Introverts, by contrast, find group situations overstimulating. Their energy comes from in-depth, one-on-one conversations, and from working and spending time alone. And they are quickly exhausted by a busy, noise- filled environment.

An extrovert’s world

Teaching, therefore, can seem an eccentric career choice for an introvert. “I really didn’t intend to become a teacher at first, because of the noise, the chaos, all of that,” says Spencer, who teaches 11-year-olds at Desert Sands Middle School in Phoenix, Arizona. “I can’t deal with a noisy classroom.”

Genevieve White similarly believed that her introversion left her singularly ill-suited to teaching. “I would never have thought I would ever have become a teacher,” she says. “It was the furthest thing from my mind.” But then she went travelling after university, and decided to stay and work in Hungary. “I fell in love with Hungary,” she says. “I really wanted to stay, but my only option was teaching.”

Fifteen years later, she now teaches English to speakers of other languages, on Scotland’s Shetland Islands.

“If you look at what are the other vocational choices for introverts, maybe it’s a relative choice,” Brian Little says. A University of Cambridge professor specialising in personality and motivational psychology, Little is himself an introvert. “Certainly, the world of business and other helping professions are equally simpatico with the orientation of extroverts.”

Introversion, importantly, is not the same as shyness. Shy people struggle to approach others and make conversation with them; introverts, meanwhile, often find conversation easy and enjoyable. But they also find being around people for too long draining, and require restorative alone-time afterwards, in which to re-energise.

Introverted teachers can tap into what Little refers to as “free traits”: the ability to act out of character for a limited period of time. When Little delivers lectures, for example, he is a charismatic speaker. But his introversion means that he needs solitude afterwards, to rest and recharge.

“Introverted teachers can do very well in the classroom,” he says. “Out of passion for your field, you can learn to create an illusion of being a strong, assertive, outgoing, gregarious person.”

“I’m not antisocial. I’m not shy,” Spencer says. He had decided to train as a teacher after running small-group mentoring programmes for a non- profit organisation. If teaching also involved small groups and one-to-one mentoring, he reasoned, then he could enjoy that, too. “I can be loud. The average person who sees me would not say that I’m an introvert.”

While he was happy to be loud, however, he realised that he could not cope with the relentless, close-quarters clamour of 30 students. And so, three days into the job, he concluded that something fairly fundamental was going to have to change.

“I was under the illusion that a classroom had to be noisy and chaotic,” he says. “I was really worried about squashing kids’ creativity. Squashing their need to be social. But I would get angry. Tired and worn out and almost unsafe. I realised that I had to create an environment where I could work, otherwise I’d just get burned out.”

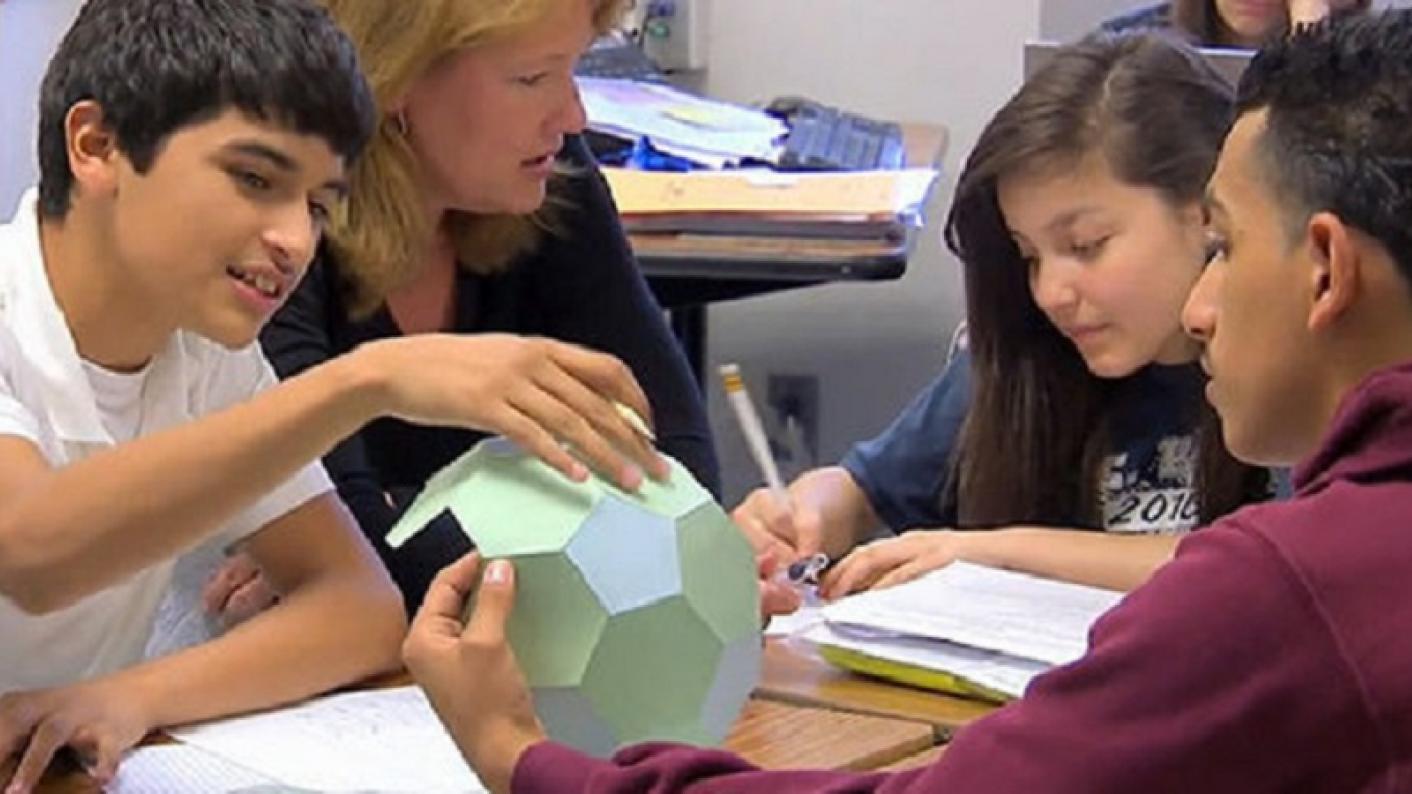

And so he began to change the way he worked. Instead of standing at the front of the class and providing direct instruction, he introduced one-to- one and small-group work. This allowed him to reduce his own levels of stimulation, replacing it with quieter, lower-key interaction with groups of students.

Reward and punishment

Standing in front of a full classroom can be particularly stressful for introverted teachers, who are quick to pick up on what Little refers to as “punishment cues”. “They will note the kid who’s rolling her eyes in the third row,” he says. “They will worry whether the material is too advanced for the kids or not advanced enough. They will monitor the sounds outside that are interfering with the progress of the kids near the window.”

Extroverted teachers, by contrast, are primarily drawn to what Little terms “reward cues”: the students who are excited or engaged. (He refers to this extrovert condition as “pronoia”: a delusional conviction that other people are plotting your well-being.) “They’ll look out and think, ‘They love me’,” he says. “They’ll be more likely to go on, oblivious to the sounds of projectile vomiting at the back of the class. Whereas the introverted teacher is aware of those sounds even before the vomiting kid.”

“Oh, yes!” White says. “But I’ve always assumed that’s just a very teacherly way to feel. I just thought anybody would strongly, strongly sense if there was somebody who didn’t feel happy in their class.

“I can’t block it out, if I feel there’s somebody in the class who’s not happy. It’s a bit ridiculous: you don’t know what’s going on in their life. It might not be anything to do with the lesson - we don’t look radiantly happy all the time. But it’s incredibly distracting.”

The second change that Spencer introduced was a deliberate loosening of restrictions. He told his students that they could use MP3 players in the classroom while they worked. “There’s enough independent time for them to work, enough time for me to walk around and observe what’s happening, where I don’t feel the need to be super-hyper social,” he says. “It’s about minimising noise and chaos. I tell them I can’t deal with a noisy classroom. And that’s respected.”

Monica Edinger, too, has rules about noise. “I’m very tough about quiet,” she says. Edinger is speaking from her classroom, at the Dalton School in New York City, where she is surrounded by nine- and 10-year-olds. But no background noise is audible down the phone line. The 18 students in her class are playing with Slinkies, almost entirely in silence.

“Certain kids are very chatty,” she says of her year group. “And I’ve been coming down hard on those kids. I do (give precedence to) quiet. It’s a part of who I am.”

On the whole, students will be teachers’ allies in the search for quiet, Little insists. “Kids in bad movies will gang up on you and tear you to shreds,” he says. “But in real life, they’ll say: ‘Hang on, Mrs Springer is a little bit anxious when we’re rowdy. So we’ll try not to be.’ It’s treating students as a potential resource, rather than as antagonists.”

Often, introverted teachers will be able to persuade hyperactive children to work in silence, because their students genuinely like them and want to make them happy. Introverts, Little says, tend to be agreeable people who shy away from confrontation: the kinds of teachers whom students like and respect. “A sweet, introverted teacher can be absolutely beloved,” he says. “The introvert is the one who makes someone feel like an individual student, rather than a blob with buttons in the third row.”

One-to-one interaction

Extroverts tend to gravitate towards large groups and free-flowing banter. Introverts, meanwhile, shun small talk, preferring the intimacy of one-to- one conversations. It is the introverted teacher, therefore, who will be more likely to stop an individual student and ask her pertinent questions about her life: how she is getting on with her new pet, for example, or whether she is still struggling with long division.

“Getting to know people as individuals is the really, really special part of the job for me,” White says. She tends to chat to her adult students during the break in the middle of their two-hour lessons. In fact, she has become so friendly with them that the relationship is almost an obstacle to her language classes. “I’ll say something during a lesson, like, ‘Tell me about the last holiday you went on’,” she says. “And you can’t really do that, because you know everything about them. It’s obviously a bit fake to ask questions you know the answer to, so you have to come up with different questions.”

Spencer has also adapted his classroom practice to eliminate introvert- unfriendly exercises. So, while he does include getting-to-know-you sessions as part of his routine at the beginning of the year, he has tweaked the usual model. “I like to choose icebreakers that get people paired up and talking, that are deep and require some thought,” he says. “Introverts want depth. They want the chance to think about their own internal life and express it to somebody.”

What introverted teachers cannot control, however, is the level of social interaction required outside the classroom. “Oh gosh, it drives me crazy,” Spencer says. “Professional development icebreakers. Walk around and find out who likes bowling, that kind of stuff. I feel like professional development is geared towards extroverts.

“I’d much rather be told that, on Thursday afternoons, you can conduct your own professional development, your own research. Find something, write something. I’d enjoy that so much more than going to a meeting.”

Meetings tend to cater for what Cain, writing in Quiet, refers to as “the Extrovert Ideal - the omnipresent belief that the ideal self is gregarious, alpha and comfortable in the spotlight”. Talkative people, she adds, are generally judged to be more intelligent, more interesting and more desirable as friends than their quieter counterparts: “We rank fast talkers as more competent and likeable than slow ones… The voluble are considered smarter than the reticent - even though there is zero correlation between the gift of the gab and good ideas.”

Finding a ‘restorative niche’

Like many introverts, Edinger functions better with time to think, and pen and paper (or keyboard) to hand. Faced with the kinds of confrontations that occasionally occur in school life, she would far rather default to written communication than face-to-face interaction. “I’m always impressed in departmental meetings,” she says. “There are a couple of people who are always incredibly articulate, able to think on their feet. That’s something I can’t do.

“I worry about speaking. How would I be able to communicate while feeling nervous and, in my nervousness, interrupting myself? I just need time to think things through. And, in contentious meetings, where you’re arguing about something, you don’t really have time to do that.”

Wherever possible, she will deal with colleagues or parents in writing: via email or a letter home. “People get skittish about email, because a lot of people can’t write very well,” she says. “But for me, oh God, it’s exhausting making a phone call to parents. The idea that somehow you’re going to do a better job by speaking to them - I don’t think it’s necessarily the case. I think introverted teachers don’t necessarily find that.”

There are some face-to-face meetings, however, that cannot be replaced by well-thought-out emails. And for an introverted teacher, still reeling from the stimulation of a day in the classroom, the idea of extending that day into parents’ evenings - and having to make small talk with a succession of strangers - is, frankly, anathema.

“The evening stuff is … urgh,” Edinger says. “It’s horrible. It’s miserable. I hate it. What I try to do is go home, rest a bit, walk my dog and then come back. But evening stuff - it’s horrible. I really, really hate it.”

Acting the extrovert with no break, Little says, is a speedy route to teacher burnout. “Creating an illusion of being an outgoing person can work wonders,” he says. “Unless it brings you to your knees.

“A key part of becoming a teacher is waking up every morning and thinking, ‘Yes, I’m a teacher!’ It really breaks my heart when you see teachers come in, full of the delight of engaging students, and then slowly having that corrode.”

To avoid this, he advocates the use of “restorative niches”, which are times and places where teachers are able to revert to introverted type. Edinger’s dog-walking, for example, functions as a restorative niche. And, after his own, relentlessly gregarious, pseudo-extroverted lectures, Little has on occasion resorted to hiding in the toilets, in order to guarantee vital restorative time alone.

Here, too, Spencer has come up with a careful strategy to ensure that the school day does not wear him down. Instead of going into the staffroom, he spends the time before school and during lunch hours in his classroom, listening to music, painting or writing his blog. “I actually just keep my door locked and the lights off,” he says.

He pauses. “There are times of the year when it’s cold, and I tell the students they can come into the classroom in the morning. But it’s on my terms. And it’s my music, which they’re not crazy about. A lot of indie rock. And if I’m at my computer, or if I have a book open and I’m reading, I want to be left alone.” Another pause. “They know that.”