The curious case of the missing psychology teachers

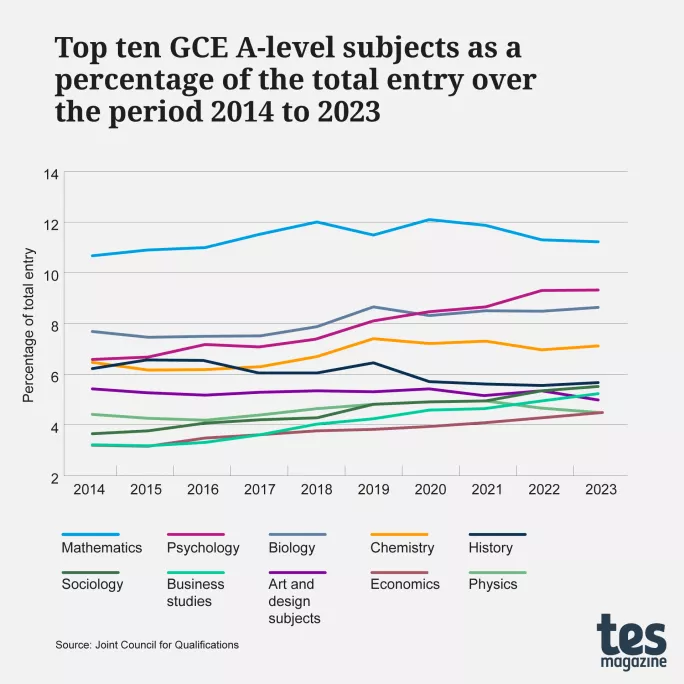

Back in August, amid the headline-grabbing statistics of A-level results day, there was a small piece of data that probably passed by many unnoticed: entries for the psychology A level passed 80,000.

This cemented its position as the second most popular A level, accounting for 9.3 per cent of total entries, placing it comfortably ahead of biology for the fourth year running.

The growth also gave psychology clear breathing space from the chasing pack, which has seen it leave biology, chemistry and history behind over the past decade. Only maths remains ahead.

So, why has psychology become so popular?

Deb Gajic, a former school head of psychology who now works for the Association for the Teaching of Psychology (ATP), says several reasons have led to this growth, from students wanting to try a new subject at A level to the rising growth of mental health and wellbeing in society.

Paddy Barber, who teaches psychology at The Polesworth School, where psychology is the most popular A level, says he has certainly seen the latter.

“I think that at a time in many students’ lives when they’re trying to understand themselves a little bit more, studying psychology gives a sort of permission to become more introspective and interested in why other people behave the way that they do,” he explains.

Meanwhile, Lucinda Powell, a former psychology teacher and now lead mentor at the National Institute of Teaching and Education at Coventry University, agrees many students like the option of a brand-new subject at A level that feels like a “fresh start”.

She says: “They might know two of their choices for A level but not really like anything else, and they see psychology and it’s new and quite cool, and they think, ‘well, I’m not bad at psychology’ [because they have never studied it] so they take it.”

A good fit

Barber says he sees this, too, but says it is important that schools are open with students about the various requirements the subject has.

He says: “I am always keen to point out to potential students that the course includes many aspects of psychology, not just psychopathology, and to make sure they know about the maths and science content as well as the extended writing needs.”

For those who are willing to take this on, Stephen Wakefield, head of psychology at Mossbourne Community Academy, says the final tick in the box is that psychology is a complementary fit with many other subjects.

“In my Year 13 class, for example, we have many students studying psychology, biology and chemistry, but also some studying psychology alongside subjects like drama and Spanish,” he says.

In short, several factors have driven psychology up the charts. What is perhaps most remarkable, though, is that, despite this growth, very few teachers are trained to teach the subject each year.

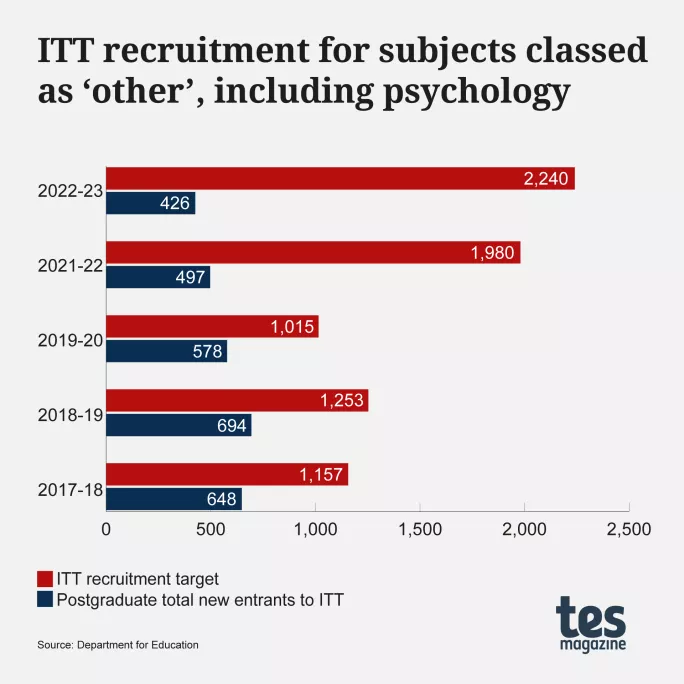

Government initial teacher training (ITT) data does not have specific data on psychology graduates, instead lumping it under “other” with media and communication studies and social studies.

Within this, from a target of 2,240 trainees for the 2022-23 academic year, only 426 were recruited - just 19 per cent of the target. The year before, only 25 per cent of the target was hit.

Tes asked the Department for Education for data on how many of these trainees within the “other” data were specified as doing a psychology course but had not received any information by the time of publication.

What’s more, there is also no data in the teaching workforce census on hours worked for psychology teachers, unlike most other subjects, with the data again buried - this time in “other social studies”. This data shows 80,305 hours taught by a total of 9,901 teachers in 2022-23.

However, the DfE’s page for this data says that “teachers may be counted against multiple subjects and key stages so sums of these categories will be greater than the number of secondary school teachers”.

Meanwhile, data on the percentage of hours taught by a teacher with qualification - ie, those with a subject specialism - shows 86.1 per cent of “other sciences” are taught by a specialist but data specific to psychology is not available and nothing was forthcoming from the DfE when asked.

The downfalls of popularity

In short, we don’t really know how many people are training to be psychology teachers, how many are teaching the subject full time or how many of those have relevant qualifications.

This may sound damning but Jack Worth, school workforce lead at the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER), says it should be recognised that as psychology is predominantly taken at A level rather than at GCSE, there isn’t the same need for teachers as in subjects such as English, maths or the humanities.

However, he says it would perhaps be good to be more “curious” about the state of applications for psychology ITT given its clear popularity.

Gajic from the ATP is more forthright, saying the mismatch between the subject’s popularity and the number of teachers has been an issue for years, meaning it is often taught by non-specialists.

“Unfortunately, that has been one of the downfalls of the popularity of psychology: a lot of schools saying to [non-specialist] teachers, ‘you have space on your timetable, so you can teach [it]’.

“This has been a problem for decades, unqualified teachers teaching psychology, and it was one reason the ATP was set up.”

‘Psychology teachers often don’t have anyone for support’

Rob McDonough, CEO of East Midlands Education Trust (EMET), many of whose 23 schools offer psychology, says “recruitment into [psychology] is difficult” given the lack of available teachers.

To tackle this, ATP offers courses to upskill teachers who want to move into teaching psychology - one of which RS teacher Barber took when he wanted to ensure a previous setting could meet student demand for the subject.

“In my former school as head of sixth form, I noticed we were losing students to nearby rival colleges and sixth forms because they offered psychology,” he says.

“We couldn’t afford to be losing students so I pitched an idea that I would set up and deliver an A-level psychology course to retain as many students as possible.”

This meant a lot of training and reading to learn enough to confidently teach it - something he says he knew “wouldn’t be easy”, but was worth it to meet student demand, and for his own professional growth.

“I absolutely love teaching psychology and the step for me from RS was an interesting and exciting one,” he adds.

Recruitment challenges

Adaptation is key from a management point of view, too, with McDonough saying they have had to approach hiring for psychology teachers differently.

“Where we tend to recruit from are staff who have been trained at a college for post-16 only,” he explains.

“This does limit deployment of staff in a secondary school to post-16 [but] the pool of these trainees is also very small so it does make recruitment very difficult.”

Furthermore, while one of EMET’s schools is large enough to justify a sole full-time psychology teacher, in other settings the teachers have to teach other subjects such as sociology or RS, which “makes recruitment into these schools much harder”, he says.

Not all are finding it as hard, though, with Mossbourne’s Wakefield saying that when they have advertised, “most applicants have had a postgraduate certificate in education in psychology”.

However, while he says recruitment is not a challenge, he acknowledges that the low numbers of psychology teachers across the sector can cause some to feel isolated - something Powell at Coventry University agrees with, adding that psychology teachers are often “a department of one”.

“There is often no one to turn to for advice or guidance on teaching a tricky topic or lesson because no one else in the school has ever taught [psychology],” she adds.

“English or maths teachers will have lots of people around them for support, whereas psychology teachers often don’t have anyone.”

Wakefield says he integrated psychology into the humanities department to ensure there are enough teachers on hand to help psychology teachers if required.

The importance of CPD

Meanwhile, Powell says it also underlines why organisations like ATP are so important, as they provide a link to fellow teachers - be that through online CPD, conferences or access to lesson resources.

“Those networks are so valuable for anyone, either a non-specialist or specialist, so you can share questions and generate ideas because there might not be anyone else in your school to ask,” she adds.

‘Restoring the bursary would be a hugely helpful step’

While schools and outside organisations are always a useful source of support, Gajic at ATP says the situation shows more should be done on the policy side, such as offering funding for subject knowledge enhancement for psychology to retain more teachers.

However, for all the opportunities that upskilling or retraining offer, it seems clear that we simply need to be training more psychology teachers. Yet that is not happening - why not?

Lack of PGCEs

One issue is simply that there are not many PGCEs in psychology, with a search of the DfE’s own “Find postgraduate teacher training courses” directory returning 105 courses at the time of writing - which Worth at the NFER says is drawn of seven university PGCEs, 30 school-centred ITT courses, 65 School Direct courses and three postgraduate apprenticeships.

This number may sound high, but a search for either maths or English at the same time returned more than 800 course options, while biology had 722 options and history 615.

Of course, these subjects are compulsory on the national curriculum, so it makes sense that there are more courses, but Wakefield says that given the clear growth at A level, it’s clear there need to be more courses on offer to meet student demand.

“This does not seem to be enough to provide every psychology student in the country with a specialist teacher,” he adds.

Powell agrees: “We need more [psychology] ITT and it needs to be more easily accessible.”

What about psychology GCSE?

Gajic says a bursary for psychology teaching should be reintroduced, too, similar to other sciences such as biology, chemistry and physics - a sentiment Wakefield agrees with, not least because he benefited from one before they were removed.

“Restoring the bursary would be a hugely helpful step to ensuring every psychology student has a teacher with a qualification in the subject,” he says.

At present, though, the DfE’s focus on bursaries is on national curriculum subjects and this seems unlikely to change.

Even if bursaries for psychology were reintroduced, it could exacerbate another issue: ITT courses require students to take classes in their chosen specialism at key stage 4, but while psychology is popular at A level, at GCSE it is a rarity.

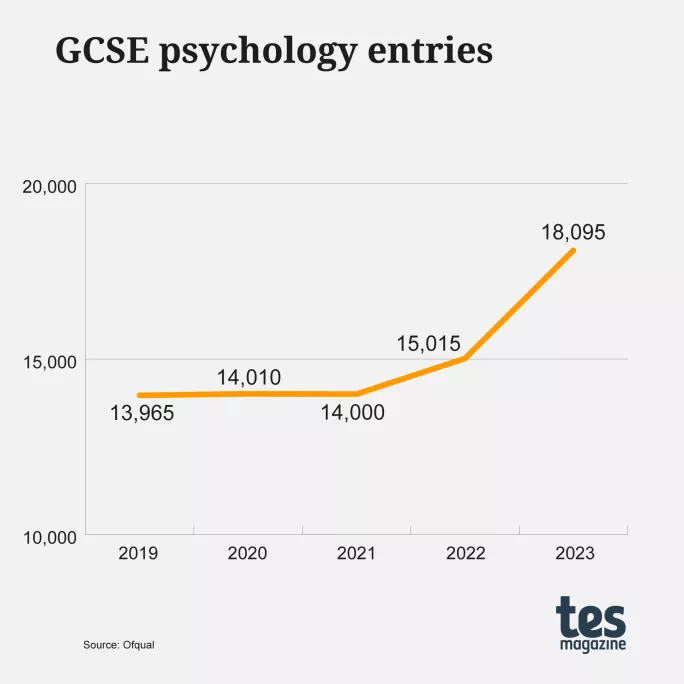

For example, Ofqual data shows that, in 2023, only 18,095 students sat the psychology GCSE, a quarter of the A-level total. This is the highest number of GCSE entries for the subject in five years (as the graph below shows), underlining a growing interest here, too.

However, even with this growth, there is still a dearth of KS4 classes for psychology ITT trainees.

“This can make it very hard for teachers to find classes to teach, so they often end up doing training in a related subject,” says Powell.

To this point, McDonough says the ITT offered through EMET’s teacher training partnership does not include psychology because “there are so very few secondary schools that offer the subject”, which means trainees “cannot find the placements to provide training for a secondary school teacher”.

Useful skills

Tes asked the DfE for comment on the various issues raised in this piece but received none.

At present, then, it seems that psychology A-level growth has happened in spite of the circumstances around the subject, rather than because of them - and it is causing issues for schools as they contend with this ongoing popularity.

Despite this, though, those who champion the subject believe that its popularity can only be a good thing, given the numerous skills it provides students, as Gajic outlines.

“It provides lots of transferable skills, eg, research methods, report writing, critical thinking and understanding of issues such as mental health,” she says.

“The majority of students might not do a traditional psychology career, but anything in which you are dealing with people - which is most things - means you will be using psychology, which is pretty useful.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article