- Home

- A-level grade predictions ‘a near-impossible task’

A-level grade predictions ‘a near-impossible task’

Predicting students’ A-level grades is a “very challenging task” with high levels of inaccuracy, according to a new study.

The researchers note that with teacher-assessed grades contributing to calculating this year’s A-level results following the cancellation of exams because of the coronavirus crisis, it is important to consider how predictions have been used in the past.

Revealed: A levels with teacher grades odds-on to stay

Exclusive: Teacher grades ignored in most GCSE results

Information: How schools can appeal GCSE and A-level results 2020

The research by UCL’s Institute of Education questions: “Why do we continue to define such a crucial stage of our education system using predictions?”

It finds that 80 per cent of teacher predictions of A-level outcomes from a previous year were inaccurate, but that using a statistical model does little to improve things.

For a working paper that studied data from the GCSE performance of more than 238,000 students who took their A levels in 2008, researchers found that when they removed opportunities for bias, they could only predict one in four students across their best three A levels accurately, compared with one in five pupils when teacher predictions were used.

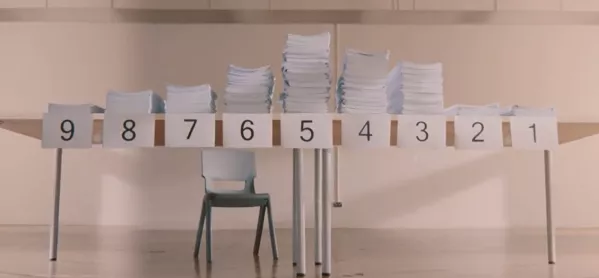

A-level results: The difficulty of predicting students’ grades

The predictions generated by the researchers’ models were inaccurate for 74 per cent of pupils, the paper says.

The researchers said the disruption to the exams system caused by the coronavirus outbreak this year had highlighted existing problems with the use of predicted grades.

When analysing the data based on school type, the researchers found that high-achieving students in non-selective state schools were 12 percentage points more likely to be under-predicted by two grades or more relative to high-achieving grammar or private school pupils.

The team found that 23 per cent of comprehensive school students were under-predicted by the models compared with just 11 per cent of grammar and private school pupils.

Professor Lindsey Macmillan, of UCL Institute of Education, who is director of its Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities, said: “This research raises the question of why we use predicted grades at such a crucial part of our education system.

“This isn’t teachers’ fault - it’s a near-impossible task. Most worryingly, there are implications for equity, as pupils in comprehensives are harder to predict.

“Our work shows that these pupils have more noisy trajectories from GCSE to A level. If you’re a straight-A student at a grammar or private school, you’re more likely to continue that to A levels. But this research is telling us there’s a lot more movement around the grades between the two exam levels for comprehensive students.”

Prior research by UCL’s Dr Gill Wyness, one of the paper’s authors, also found that just 16 per cent of A level candidates were correctly predicted across their best three A levels, while 75 per cent were over-predicted and 8 per cent under-predicted.

However, the same study found that the grades of high-achieving students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds were more likely to be under-predicted.

Dr Wyness said: “We definitely don’t think teacher predictions should be replaced by computer predictions - this research serves to highlight the difficulty faced by teachers, and provides further evidence that the UK’s predicted grades system should be re-examined.”

The research published today used statistical models and machine learning to analyse student data, yet found this only made “modest” improvements to the accuracy of grade predictions.

However, the accuracy of the statistical prediction was improved when data on “related” GCSEs was included - for example, students who studied chemistry at both GCSE and A level.

But the accuracy of predictions varied across subjects, as “while English literature is well-predicted across the range of achievement, maths and chemistry are harder to predict among low achievers, and more accurately predicted among high achievers”.

Law was difficult to predict among all levels of achievement, and for subjects without related GCSEs, the task was even more difficult.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters