It is important that the gender pay gap in Ofsted has been made public, but we shouldn’t be surprised by the findings that men in Ofsted are paid on average 8 per cent more than women and receive about 20 per cent more in bonuses.

Like so much in education and elsewhere in the “higher” ranks of both the public and private sectors, discrimination in the inspection service has mirrored discrimination more widely in social attitudes and has done so since the inception of government-based school inspection in 1839.

The very first people appointed as her majesty’s inspectors (HMI) were Rev John Allen, an “examining chaplain”, and Hugh Tremenheere, a barrister - neither were teachers by profession. Most of their early successors followed careers in the Church, university or law. That was an early form of discrimination against those working in schools; presumably they were seen as too complicit in schooling to provide an independent, reasonably objective view. Even today the chief inspector, a political appointment, is a non-teacher.

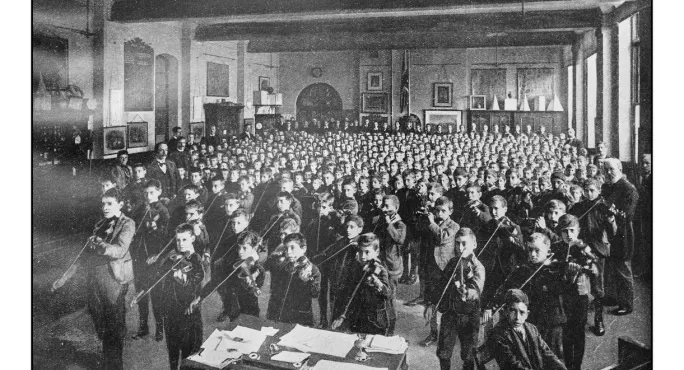

Until 1870, almost all government inspectors had been to Oxford or Cambridge and all had been independently educated, though their work focused on voluntary schools in receipt of government grants - a very different educational and social milieu. The disproportionate representation of independent teachers as HMI persisted throughout the 20th century - a form of discrimination against those in the state sector.

There has been discrimination, too, against those working in elementary and later primary schools. Initially, the former could not be appointed as full inspectors but could only serve as assistants. It wasn’t until the 1890s that the first elementary school teacher became an HMI. A century on, there were still far more ex-secondary teachers than ex-primary ones in HM Inspectorate pre-Ofsted, and far fewer of the latter in senior posts. It is telling that only one former primary school teacher has even been appointed head of either HM Inspectorate or Ofsted, and only two have ever been designated as directors of inspection.

Gender discrimination in public service

Needless to say, the vast majority of early inspectors were male. The first female inspectors weren’t appointed until 1896, but then only in the post of “sub-inspector(women)” - nicknamed the “washtub women” by the men and limited to matters dealing with women, girls and younger children. Along with inequalities in responsibilities came considerable differences in salaries, which were not rectified until the 1930s. As late as 1990 there were still far more men than women HMI and far more in senior posts. Only one female senior chief inspector was ever appointed. Even today more men than women hold senior posts within Ofsted.

And in line with practice in the civil service, there was discrimination against married women. Before the Second World War they were expected to resign on marriage. As late as 1970, a new female recruit was told that four married women had just been appointed, which had never happened before, and in the future there would never be more than “could be counted on the fingers of one hand”. That situation, at least, has changed for the better since 1970.

And then in 1992 along came Ofsted - with, as before, fewer female than male chief inspectors, but initially with a more balanced (but never equal) representation of males and females. This was upset by the later expansion of Ofsted’s responsibilities to include social services, which resulted in the recruitment of many more female inspectors paid on lower pay scales to reflect the lower status of social work compared with education - another form of discrimination, still very much with us.

This article is not intended as “inspector-bashing” but to point out aspects of discrimination that have characterised educational policy and practice more generally over the past century and a half. Such forms of discrimination have undoubtedly been replicated in other branches of public service.

Given the past, perhaps we should be surprised that Ofsted’s salary disparities, although regrettable, are not even bigger?

Professor Colin Richards was formerly staff inspector for the curriculum and editor of the Curriculum Matters series

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and like Tes on Facebook