Science after Sats

Or were the tests simply an easy sacrifice on the altar of political expediency?

The final key stage 2 national curriculum test in science did not get much of a send-off. Ed Balls, the Schools Secretary, announced its demise just four days before Year 6 pupils around the country opened their test papers to demonstrate what they had learnt over the previous four years in junior school.

They were asked, for example, why washing up bowls are made of plastic, why folded paper falls more quickly than unfolded paper, and what they thought was in those tiny holes in cakes. Those pupils who answered, in turn, “it’s insoluble”, “air resistance” and “raisins” are on their way to level 4, while those who responded with “air” for the last question may even achieve level 5 (although a slightly less tasty cake).

Last year, 88 per cent of pupils achieved the expected level 4 for their age group (10 to 11-year-olds) and 44 per cent got level 5. Eleven years previously, in 1997, only 69 per cent of pupils reached level 4.

So why would the Government want to scrap Sats in science when pupils have improved over a decade, when they do better in this subject than in English or maths, and when they score well in comparison with other countries? And what does it mean for the discipline of science as a school subject?

Politically, the test is easy to sacrifice. It is a less sensitive topic than English and maths because there is no national target for science. And it does not have the same emotional resonance for the media as numeracy and literacy in a culture that regards those who can understand what goes on in laboratories as boffins.

Not only is the science community in agreement with scrapping the test; it is positively delighted. It sees this as a solution to the two entwined problems that it believes hold primary science back: the type of science taught and a distinct lack of enthusiasm for it.

Liz Lawrence, chair of the Association for Science Education’s primary committee, says: “It could be an extremely good thing. Sats tend to focus teachers on what can be tested. There is a perception that Sats involve fewer inquiry skills than they do, but they do leave teachers to go for recall and what can be tested with pen and paper.”

There has been some reform to science Sats to reflect the importance of developing pupils’ skills in inquiry. This year, for example, one question asked them to plan an investigation to find out whether ice cubes melt more quickly in cool bags or carrier bags.

But other questions supposed to be infused with the spirit of inquiry included one where Sanna, a young girl, is shown investigating which materials are good reflectors of light. Underneath her picture and a description of what she is doing are three questions on reflectors which depend more on knowledge than pupil discovery.

Mrs Lawrence says: “Children need knowledge, but science is far more than a body of knowledge; it’s a way of learning about the world. You can’t understand something as evidence-based unless you have first-hand experience of collecting evidence.”

This analysis of science Sats is supported by a damning paragraph in the report recommending the abolition of KS2 science tests by the expert group on assessment which was published two weeks ago. The report stated: “The summative assessment of the KS2 science curriculum is not best done through an externally set and marked written test . KS2 English and maths results better predict later achievement in science than the KS2 science test does.”

The expert group made of five educationists - including Sir Jim Rose, who recently concluded a review of the primary curriculum - recommended that teacher assessment would give a better sense of how children were doing in the subject, and would prevent the skewing of the science curriculum towards learning facts.

This over-emphasis on facts at the expense of investigation has also been recognised by Ofsted, which stated in its Success in Science report last year, “None of the primary schools visited had an inadequate science curriculum. However, in a small minority (one in 20), it was too narrow and relied too heavily on worksheets. Year 6 pupils in particular were too often involved in practising responses to national test questions rather than engaging in exciting science work; they did not develop a thorough understanding of the subject and their interest and enthusiasm were low.”

The report said that while test scores were good, there was scope for improvement. To do this, as well as meeting test requirements, some teachers needed a better understanding of science, it said, citing a teacher who, when asked by Year 1 pupil why one penny was attracted to a magnet while another was not, replied: “That’s a funny magnet.”

Dylan Wiliam, professor of educational assessment at the Institute of Education at London University and a co-author of Inside the Black Box, an influential study of the role of assessment, says: “KS2 science not being assessed through a timed written test is absolutely right. It doesn’t need to be an external test. When we think what pupils ought to be doing in science - exploring, learning, forming arguments - that is not best assessed through a test, but through observation and teacher judgments.

“However, parents will want to know scores in Newcastle are the equivalent in Cornwall. It’s not that teachers cannot be trusted, but teachers don’t know what (other) schools are doing. There needs to be some mechanism for assuring standard judgments. Some process needs to be found if we are to have faith in the levels that teachers award.”

The expert group has recommended more training for teachers on assessment and assessment tasks for science. The National Strategies is developing materials for primary science in its Assessing Pupils’ Progress series. It has not recommend sample tests at KS2, but Ed Balls has asked for these in addition to teacher assessments. These tests will be aimed not at measuring individual children’s knowledge, but at ensuring standards over time and in comparison with other countries.

England already takes part in Timss (Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study), which is carried out every four years. In 2007, England’s primary score rose from 540 to 542, although it slipped down the rankings from fifth out of 25 countries to seventh out of 36.

The National Foundation for Educational Research, which carries out the Timss tests in England, also found that the proportion of primary pupils with highly positive attitudes to science fell from 76 per cent in 1995 to 55 per cent in 2007.

Test revision could be one reason for this lack of enthusiasm, but how different will the curriculum be without tests?

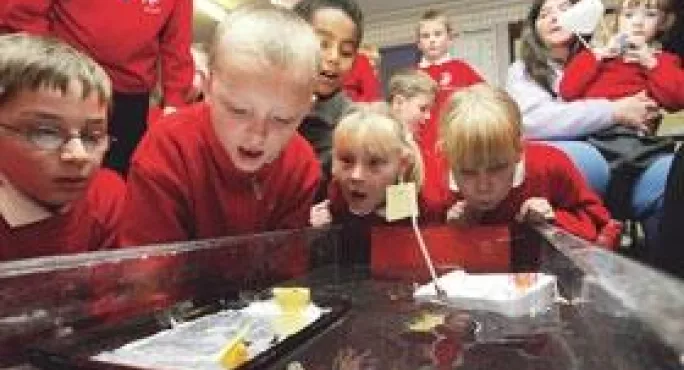

Colin Fleetwood, head of Grenoside Primary in Sheffield, one of six primaries in the city that are being trialled as science specialists, said: “Our main focus is scientific inquiry and developing inquiry skills. My personal view - and I think this is fairly widely held - is that the most important thing in terms of childrens’ science education is to enthuse them about science and the world around them.

“Science develops children’s investigative skills, so they can carry out investigations into all sorts of things.

“There will be more opportunity now Sats have gone to focus on scientific inquiry and children’s interest in science, to spend more time developing those skills and using them rather than going through revision books and learning lots of facts.”

How to fill a vacuum

What happens now? 200910 Summer 2010 201112 From Sept 2011 Summer 2012

Additional content:Take a look at our Assessment forum

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters