- Home

- Transition: three changes to support vulnerable children

Transition: three changes to support vulnerable children

Since becoming a Sendco almost four years ago, I have become aware of an increasing number of young people without the necessary skillset to make a smooth transition from primary to secondary school.

I am not focusing on those with identified additional needs here, as although the transition can be challenging for these youngsters, at least schools can work together to ensure that as much is put in place as possible.

The difficulty seems to lie where students are arriving at high school with no identified needs, but with difficulties such as not being able to physically write by hand or type; extremely weak literacy and numeracy skills; social, emotional and mental health issues - these are just the most common issues.

What is the impact of these challenges? School refusal, behaviour problems, exclusions, severely impacted learning progress, acute emotional issues.

Quick read: Why research suggests we should ditch the Send labels

Quick listen: What teachers need to know about dyslexia

Want to know more? The myth of inclusion

Let me be clear: this is not a criticism of primary schools. No school would purposefully set out to harm a young person’s future prospects.

But what the rise in these issues does suggest is a lack of joined-up thinking across the primary-secondary divide, a lack of communication, and a lack of training and financial support.

So how do we begin to make things better?

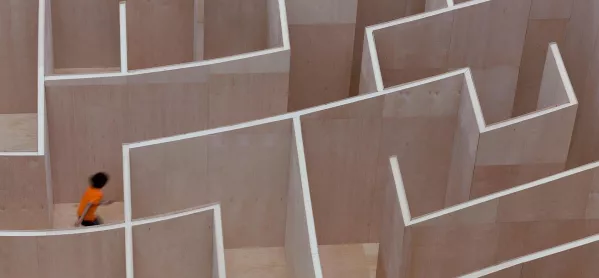

1. Acclimatisation

I think we often underestimate just how big a cultural and environmental shift moving from primary to secondary school actually is. Primary schools, particularly the very small ones found in locations such as rural Norfolk, are far less intimidating and far more able to provide one-to-one or small group support (eg allocating a TA to scribe for someone with illegible handwriting).

When these young people come to secondary school, they find themselves in a much larger and more frenetic environment, with fewer opportunities for individual or small group support. This, combined with a surge of hormones, can lead to a perfect storm.

We need more than just “taster” days. By working together, schools can start earlier to begin to give children experience of more frenetic, independent environments. Year 7 and Year 6 teachers should be working together to create the best solutions for a particular cohort and for what is logistically possible.

Can the primary school use the secondary school site for certain sessions? Can the secondary school put on experiences that primary children are invited to? Teachers are creative by nature, so let’s point that creativity in the direction of transition.

Primary and secondary schools need to work more closely together, so that there is a greater appreciation of what secondary school is like from the primary school perspective, as well as an understanding of the environments the new cohort have come from, from a secondary school perspective.

I truly think more shared training sessions could take place among primary and secondary schools and this would bring multiple benefits.

2. Don’t be scared of diagnosis

There can be an aversion towards the culture of ‘“labels”, which on one I hand I can understand, but without a “label” it is extremely difficult for schools and families to know how best to support their young people and it can promote a culture of “making do” - if the child is managing, then why bother with a label?

The trouble is, what happens when the child stops managing? What happens if that is at secondary school and the teachers have none of the context of previous behaviour and concerns with which the primary school teachers were armed?

Difficulties with speech and language, literacy and numeracy are perhaps more obvious, but there are other conditions that may present themselves more subtly or can be quickly dismissed as a child being “naughty”.

One issue I am experiencing with increased frequency is the number of girls with autism not being picked up early enough, resulting in issues with mental health and school attendance.

I can understand this, as autism in girls is only really just being recognised (assessment criteria are very much skewed towards males). However, I am constantly surprised when speaking to parents/carers that what seem obvious indicators are missed.

For instance, a parent told me her daughter regularly hid under the desk at primary school, barking at others.

Perhaps primary schools are more open-minded and accepting of “quirks”, which in many ways is great, but also has the potential to set youngsters back when they to struggle to regulate their behaviour in a secondary setting.

Looking at behaviour and seeking out the reasons for it, even if that child is managing to access the curriculum and social situations in the short term, is essential for the long-term success of the child.

3. Secondary schools: recognise the funding may be more useful earlier

On all of the above I am very aware that in the current climate, seeking and obtaining any diagnosis can be a lengthy process (not to mention potentially expensive), as can getting an Education and Health Care Plan.

Although I am potentially cutting off my nose to spite my face, I would prefer to see resources redirected to primary schools - particularly to the early years, so that teachers and TAs can receive the necessary training to identify potential additional needs, as well as then having the funding to have their young people assessed and then properly supported.

It is my feeling that this would not only be better for the students, their families and their teachers, but it would also make economic sense, and would reduce the burden on the NHS and services such as CAMHS, further down the line.

Gemma Corby is Sendco at Hobart High School, Norfolk. You can read all her articles on her Tes author page

Further reading

- Transition 101: are you getting it right?

- The UCL STARS transition study

- Four ways to tackle working memory challenges

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters