- Home

- Undermined, underused and misunderstood: life in schools for Sendcos

Undermined, underused and misunderstood: life in schools for Sendcos

Sue is an experienced special educational needs and disabilities co-ordinator (Sendco). She’s been one long enough to know the system. Long enough to know how it works. Long enough to know she rarely, if ever, wins.

But Sue still fights.

Today she’s worried about Jay. Next year, he will take an English literature exam despite his severe language difficulties. He won’t pass. The likelihood is that he won’t pass any of his GCSEs. Yet he has to sit these exams - spend all of his time preparing for them - because when it comes to outcomes, this is what is valued. If he can scrape even the lowest grade, then the school has achieved. A child with SEND - they’ve got him a piece of paper. It’s a result.

Sue doesn’t agree. She became a Sendco to ensure that all children had the best chance of life. She knows that in this regard, for Jay, the school has failed.

“Will we have actually helped him on his way through life?” she asks.

“When the senior leadership team (SLT) talk about outcomes, they mean grades and points, but I would sooner he leaves us being able to function in society, look after himself and have hope for the future.”

- This was originally published in Tes magazine. To get great content every week, click here.

Sue can’t force the school to approach Jay in this way. She’s not part of the SLT, so she can’t lead or advise strategically; she’s denied the power she requires to even make a dent in his needs.

The role of Sendco is not what she thought it would be. It is not what she believes it could be. It is not what she knows it should be. And she’s not alone. There are Sendcos across the country who feel the same way.

It isn’t supposed to be like this. The presumption of inclusion means that children and young people with SEND should expect to have their needs met in mainstream schools - whatever those needs happen to be - and the Sendco is supposed to make sure that happens. It’s written down in policy and in law. But as with much of education policy, and especially so of inclusion and SEND, what we get is a disconnect, a mish-mash and a muddle. The reality is that the role of the Sendco is hugely variable: much of it is misunderstood, much of it is under-resourced and much of it is under-respected. Inclusion is stalling as a result and, if we’re not careful, it will fail.

Every school is affected

Every school in the country has a Sendco, even the top-performing grammar schools. If they don’t, they’re in breach of the law. And there is good reason why they are there.

England has about 1.2 million children with SEND. Around 991,980 pupils receive SEND support. In the 2015-16 academic year, 13.4 per cent of children in state-funded primary schools had SEND and 12.7 per cent of children in state-funded secondary schools did so. As such, every individual state school will have significant numbers of children with SEND, both already identified or in need of identification.

The variety of need is vast. The 2014 SEND Code of Practice (CoP) defines four broad categories, but the reality is that every child is different, their needs are unique and it’s not always about attainment or the lack of it.

It’s the job, according to the CoP, of every teacher to teach those children as they would any other - every teacher is a teacher of special educational needs. But it’s not easy, teachers need support, and that’s where the Sendco should come in. That role is meant to be the focal point, the driving force, the main support mechanism for inclusion.

It seems odd, then, given the huge responsibility a Sendco should have to so many lives, that no one really knows what a Sendco is supposed to do or the skills required for the role.

“Part of what I am looking at currently is what a Sendco is doing - what they actually do versus what people think they do,” says Helen Curran, lecturer in SEN at Bath Spa University. “I don’t think people do understand the role.”

Part of the problem is a lack of definition from above. The Department for Education (DfE) seems reluctant to be too prescriptive. According to the CoP, he or she must be a qualified teacher employed at the school, and they must hold the Sendco Award (a master’s-level qualification that covers educational leadership, theories of disability and inclusion, as well as practical strategies to help children experiencing a range of difficulties), or have it within three years.

The Sendco should carry out a number of operational and strategic duties detailed in the CoP, which include being available to give professional guidance to colleagues, liaising closely with other professionals and overseeing the day-to-day operation of the school’s SEND policy. But it seems that even those at the very top are confused by the role beyond this and what aim, scale and authority these duties should have.

For example, responsibility for special educational needs and disabilities lies not with the minister for schools but, since July 2016, with the minister of state for vulnerable children and families, currently Edward Timpson MP. The department, it would appear, isn’t sure whether SEND is really about learning, or care.

Perhaps this confusion provides an opportunity for self-definition, but as it is only “advisable” that the Sendco has a part to play in the strategic development of the school, as a member of the SLT, their ability to define their own role - as the person most likely to know what is needed - can be very limited.

Leaving that job of definition to others is problematic. It’s not just about what people do not know about the role of Sendco that complicates matters but also what they think they know. The role of Sendco was created in 1994, back when the watchword was integration rather than inclusion. Since then, in the subsequent CoPs of 2001 and 2014, it has undergone the sort of tweaking that has muddied the water.

At first, the role was largely operational: someone to make sure paperwork got done. With the 2001 CoP came an increased focus on inclusion and the idea that the Sendco needed to be a leader, as well as a manager. Since 2008, in an attempt to raise the status of the role, the Sendco had to hold the Sendco Award. From 2014, the Sendco became the lynchpin, the meeting point, the person who not only co-ordinates the school, but social services, health and family, too.

As a result, teachers who have worked throughout that time have very mixed ideas about what a Sendco should do - and have passed that down to younger teachers. What we are left with in schools is a ramshackle Heath Robinson affair: a creaking, inefficient impression of the role made up of different parts, some of which have long since ceased to be applicable.

Not all understand inclusion

With a lack of guidance from above and mixed definitions among the teaching profession, the role of Sendco becomes heavily dependent on the context and leadership of an individual school. If everyone in education fully understood SEND and realised - and saw the necessity in - what was needed, then this would not be a problem. The trouble is that far from everyone in education believes in inclusion, or prioritises it, and plenty more don’t understand it.

Where the headteacher has a vision for inclusion, it is likely that the Sendco will be, as is advised in the CoP, on the SLT. They will also have a clearly defined role and the philosophy of inclusion will be one that is ingrained in the school culture.

“As I see it, the head is ultimately responsible for the success of inclusion,” says Mark East, headteacher of a primary school in Devon.

“The Sendco knows the processes and the support that can be provided, but it is the head, class teacher and support staff who know the children and the families. If a school is to be inclusive, it has to have an ethos that everyone is signed up to.”

Distributing responsibility across the staff like this, enabling the Sendco to be a point of reference rather than hidden under a mountain of paper, makes everyone’s life easier - staff and students. Unfortunately, there are criminally few schools like this.

Where the headteacher is not so convinced about inclusion, or where their priorities lie “elsewhere”, the role is less clear cut. In some primary schools, for instance, the Sendco can be expected to perform the role in one afternoon a week, in between a full teaching load, with no voice on, or input into, the strategic direction of the school.

“‘Strategic’ would imply that I have a say in the way SEND provision is co-ordinated and the corresponding budgets,” says a Sendco in a primary school, who wishes to remain anonymous and who squeezes her role into two hours out of her three days a week. “I fill in Education, Health and Care Plan (EHCP) paperwork, complete referrals and speak to parents. The other roles are mine in principle, but the head and deputy make the decisions.”

The role can be just as powerless in secondaries. “Three years ago, I was more in leadership, as I introduced whole-school intervention, which impacted many teachers and supported a lot of pupils,” says a secondary Sendco. “Despite outstanding results, this was stopped a year ago by the SLT, who were not grasping the extent of our pupils’ weak literacy and learning abilities.”

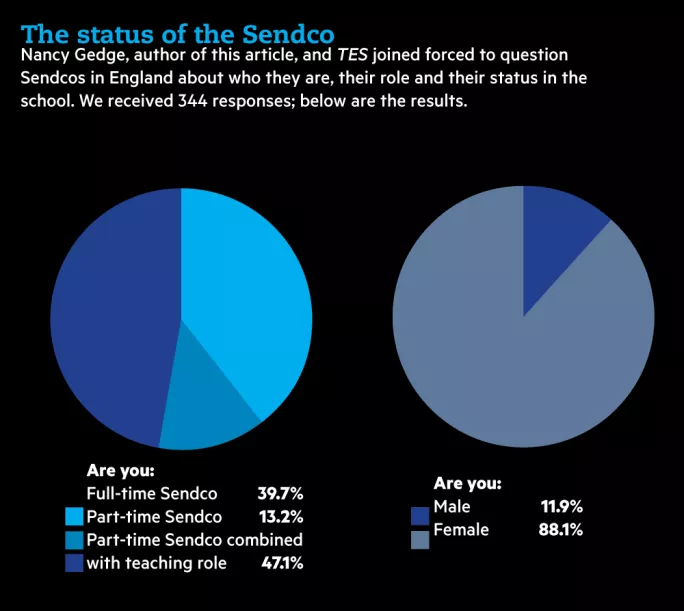

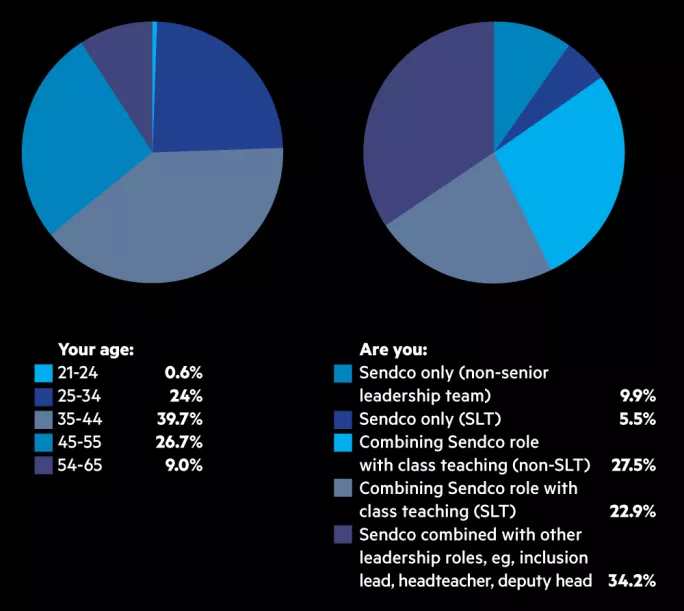

These incidences of the influence of Sendcos being marginalised or curtailed are not anomalies. A survey of Sendcos in England I ran, in conjunction with Tes, highlights how different the role of Sendco can be between schools. Despite CoP advice, just 62.6 per cent of the 344 respondents to our survey were on the SLT of their school.

The majority of respondents also combined their Sendco role with other responsibilities; only 5.5 per cent of those on the SLT worked purely in that capacity.

The overwhelming majority - 57.1 per cent of Sendcos on the SLT and 84.6 per cent of all Sendcos - combine what they do for children with SEND with their role as child protection officer, headteacher, English as an additional language co-ordinator, assessment co-ordinator, looked-after children co-ordinator, or within their planning, preparation and assessment time.

Let’s be clear, this was never a part-time job, even if giving it to someone already on the SLT ensures that their word has automatic clout. After the 2014 CoP, it is almost impossible to even squeeze it into full-time hours.

EHCP and Team Around the Child/common assessment framework paperwork, referrals, emails, targets and provision mapping take up much of a Sendco’s time; by making the field of education, rather than health and social care, the locus of accountability, it is Sendcos who are left - tied to the telephone chasing up people whose attendance at meetings for vulnerable children could make a huge difference - navigating their way through a new realm of paperwork.

“I need an additional body to be admin support, as the role is unmanageable,” says a Sendco from our survey.

“I spend most of my time on the phone, filling in paperwork and analysing data.”

Another Sendco says: “It is a never-ending series of plate-spinning scenarios. The operational stuff is exceptionally easy to get sucked into, so I have to be strict with myself and have proper blocks of time set aside for a ‘strategic push’. Of course, this isn’t helped when people come to you and demand you put it aside because child x has just done y and it’s ‘obviously a special-needs issue’.”

Again, these are not isolated experiences.

“Time was already a critical factor for the role, and now there are major changes to bring in, support staff, parents, etc, while also doing the day job,” says Curran. “[After 2014] it became even more squeezed and all set within an educational backdrop that is very challenging - [there’s] a lot of policy conflict that Sendcos are having to negotiate.”

A shortage of time, combined with the lack of strategic power, means that entrenched views about Sendcos are burrowed ever deeper into teachers’ psyche. It can make it very difficult to get classroom teachers to understand what the role is supposed to be, says Katie Smith, a Sendco from Oxfordshire.

“What I don’t think they see is all the paperwork involved. I have to delegate a lot, as I have limited time. I know that they would like to see more of me, for example, observing their pupils, supporting them and their teaching assistants with interventions, but time really only allows for paperwork. On the occasions where I get in to classes, we always make positive changes, so I know I need to be out there doing more of that.”

When the Sendco is restricted, so is their impact on outcomes for vulnerable youngsters. Instead of joined-up thinking, what you get is confusion among staff and students. Cracks appear and children with SEND fall between them.

Call for clarity

So, what can we do? For a start, we need more guidance on what a Sendco should be.

Unfortunately, the DfE is unwilling to go too far beyond what it has stipulated before in clarifying the role. What we get is a restating of the CoP. “A Sendco has an important role to play, with the headteacher and governing body, in determining the strategic development of SEN policy and provision in the school,” says a DfE spokesperson. “That’s why we require all Sendcos to be qualified teachers. It is down to schools to decide how the Sendco fits into their wider structure, but we are clear that they will be most effective if they are part of the school leadership team.”

Ofsted isn’t much help either, suggesting that some schools might not even need their own Sendco.

“Ofsted expects that all schools will have a Sendco, in line with the SEND CoP,” says a spokesperson. “There may be circumstances where that individual is employed to work across a number of schools - for example, where the schools are small.”

They add that the Sendco may not even be spoken to during an inspection: “While inspectors will not always meet with the Sendco during inspection, unless there is a reason to do so, they will look for evidence that shows they are working effectively, and that the school is meeting its wider responsibilities in relation to the CoP.”

How they can do that without talking to the person ultimately responsible for co-ordinating (the clue is in the title) those responsibilities is a mystery.

With little help from above, all we can do is change ourselves. As teachers, we need to get informed. We need to examine honestly our own barriers to teaching. Are we, even just a little bit, afraid? Do we, when it comes down to it, feel that we just don’t have it in us to teach a child with SEND?

Headteachers need to understand what inclusion is, what it is for - and the pivotal role that they play in it.

Those two factors should force the issue on SEND and bring about a better definition, use and respect for the Sendco role.

We must do this soon. If we carry on as we are, we will continue the slow sleepwalk into segregation. The SEND lottery of patchy provision will only go in one direction, as schools with effective Sendcos and an inclusive ethos act as honeypots for parents, desperate for their children to receive a decent education; others will meet with the sort of places where children are gently but firmly turned away, an informal “we don’t think your child would fit in here” ringing in their ears.

Children will continue to travel along the school-to-prison pipeline - and we will have done nothing to close the biggest gap of all.

Let’s take the lack of official clarification and use it to our advantage. Let’s see it as an opportunity to shape our own profession for the better. Let’s stand with the courage of conviction when it comes to the role of Sendco. Because if we don’t, we don’t just let down those students with SEND, we let down every child and every adult in every single school in the country.

Nancy Gedge is a teacher and consultant teacher for the Driver Youth Trust.

Want to keep up with the latest education news and opinion? Follow Tes on Twitter and like Tes on Facebook.

- This was originally published in Tes magazine. To get great content every week, click here.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters