Is all-through really all-that?

It’s not that Ed Vainker and his team were disappointed. How could they be, when the first cohort of students at their South London free school, Reach Academy Feltham, achieved some of the best GCSE results in the country, a third gaining 5 A*-As and 93 per cent at least 5 A*-Cs, including English and maths?

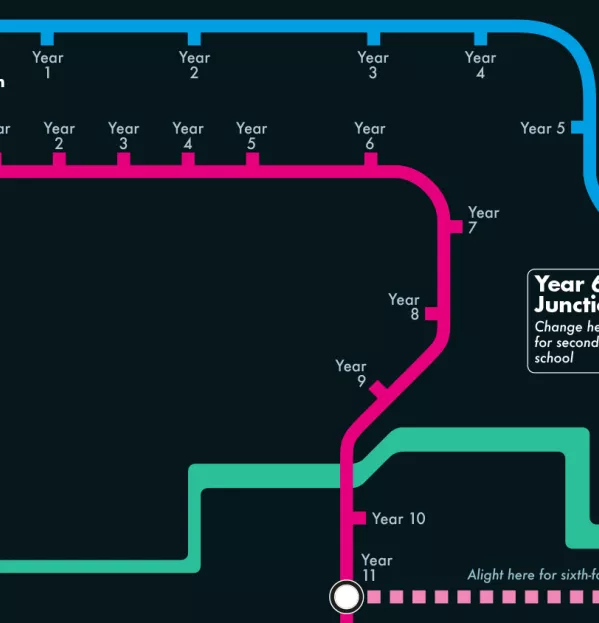

It was more that they believed those results could have been better...if only they had founded the school six years earlier. You see, this year’s GCSE students attended Reach only from Year 7. In six years’ time, the students taking GCSEs will have been at the school from the age of 4. Reach is an all-through school and Vainker believes that once they have students for the full 11 years of education, it will make a huge difference to what the school can help them achieve.

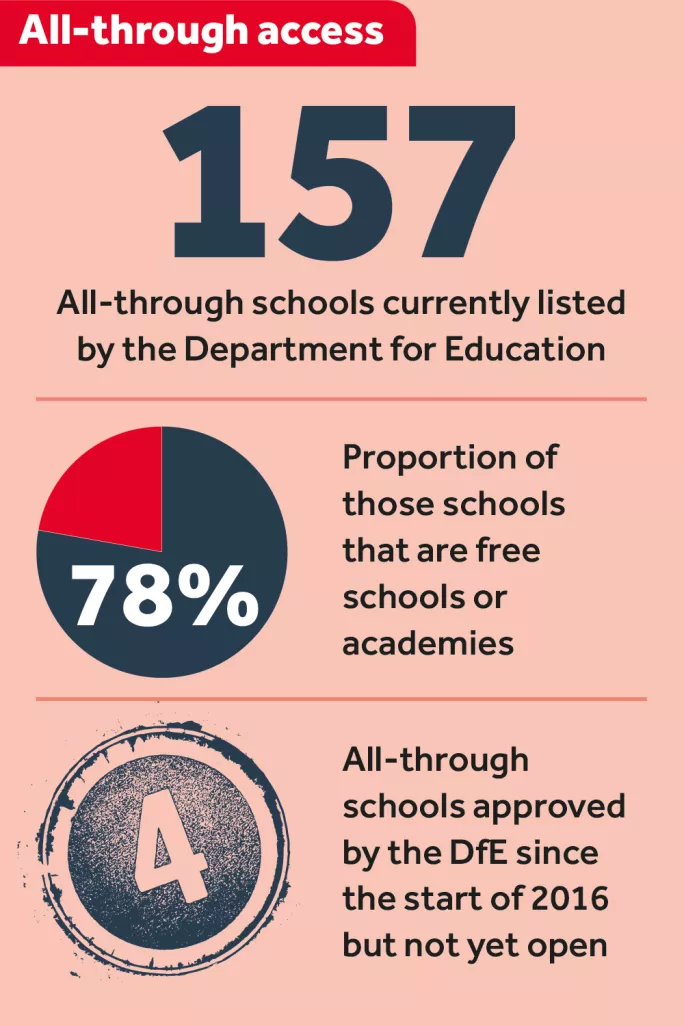

Reach is one of many free schools to opt for the all-through model. Around 16.8 per cent of free schools are all-throughs - compared with approximately 0.6 per cent of the total number of schools in England. And the numbers are growing: in 2010, there were 13 all-through schools in England.

The free school programme ballooned the numbers: by 2015 there were 113 all-throughs and by October this year there were 157.

Why have schools flocked to the model? Like Vainker, many free-school founders believe it not only solves multiple transition issues, but also has numerous learning benefits. Impressive results at Vainker’s and other all-throughs, such as King Solomon Academy in London, suggest they have a strong case.

But not everyone is convinced. Some even question whether they are detrimental to a student’s development.

The battle between those opposing views is an important one: it could determine - alongside the huge logistical challenges large scale all-through adoption would represent - whether these early sparks of an all-through revolution will catch and spread, or die away, perhaps this time for good.

The government claims to be agnostic on models of schooling.

“We want to develop and maintain a high-quality and diverse school system - and all-through schools are part of this,” says a Department for Education spokesperson.

And those within the free school movement claim all-throughs are part of a broad embrace of innovation.

“Part of the rationale for the free-school programmes was that it would create a space in the public education sector for innovation,” says Toby Young, director of the New Schools Network. “One of the innovations that has emerged through that programme is the all-through model. When designed in the right way it is proving to be very effective.”

But it is hard to ignore the fact that the all-through model is proving very appealing to both those setting up free schools and those approving them. Combined with positive noises about all-throughs from government, there is the appearance of a determined push in this direction.

And when you listen to advocates for the model, you can see why.

Co-planning the curriculum

On a practical level, it is argued that all-throughs can achieve economies of scale both in terms of increasing an institution’s buying power and in sharing resources (see box, page 35). At a time of tight budgets and difficult recruitment, being able to pool resources - both financial and human - across phases is potentially beneficial.

But the main benefit cited is that the model allows for greater consistency in terms of what is taught and how it is taught - not only with cross-phase CPD but also with curriculum planning.

“The biggest benefit is that you have the capacity to structure a curriculum from 3-16 without having to guess at what happened before or what’s going to happen afterwards, as you do with traditional schools,” argues Keziah Featherstone, who was until recently headteacher at the Bridge Learning Campus in Bristol, which became an all-through in 2009 in a merger between two schools.

Vainker agrees: “I trained to teach French and history. Teaching both of those subjects in secondary schools, you were basically starting from scratch. You had pupils in front of you who had come from 15 different primaries, they all had different experiences of those subjects and they often had different experiences within the schools, too.”

Fixing these cross-phase difficulties around curriculum could be feasibly achieved through close working with the feeder primary schools, but for those with multiple feeder schools, it would be a logistical nightmare and heavily dependent on the willingness of the primary schools to be dictated to by the secondary, or at least to co-plan with a multitude of other primaries and the secondary.

But it’s not just the yawning gap of curriculum that the all-throughs are talking about here: it’s the consistency of the ethos, style of teaching, attitude and physical setting of the schools that is beneficial, they say. The children are comfortable in the school, everyone knows each other better - the teachers know the students and their families and the students know the teachers and the environment.

That has the potential for better outcomes academically - teacher-student relationships are so often cited as one the biggest factors in attainment - but also happier children.

That could be particularly true of those with special educational needs and disability. You stand a better chance of avoiding the communication issues that can leave vulnerable children lost when they move from primary to secondary: long-term plans and in-depth knowledge of the child’s needs should be in place.

Essentially, the Year 7 dip in attainment of all students, because of transition, should be banished in an all-through system.

Yet is there any evidence any of those theoretical benefits stack up?

That there is an issue with transition is extremely well-evidenced, but that all-through fixes all the problems is less clear.

Jennifer Symonds is a lecturer in education at the School of Education, University College Dublin, specialising in how engagement, motivation and well-being develop within educational settings and across educational transitions. She says the shock of transition can be dramatically reduced in an all-through environment because the continuities are increased.

“The school buildings are going to be familiar,” she says. “They would also probably have the opportunity to have met the senior school headteacher or possibly members of the management team and they might have been taught by some members of the senior school staff during their time in primary education so they would have more familiar faces.”

In very small all-through schools, such as Reach and King Solomon, the positive impact could be felt even more.

And yet, just because an all-through is situated in the same grounds and has joint leadership, it does not necessarily mean the transition is seamless. Some who work in all-throughs claim the two phases in their setting operate as separate entities. Another issue is that many all-throughs add extra form groups when the secondary phase begins: how you merge those that have been in the school from age 4 with new students can be tricky.

Moreover, the transition benefits of all through can have corresponding potentially negative impacts, says Symonds.

“Young people want to see signals that they are growing up and are growing older because they are on their way to becoming a teenager and then a young adult,” she explains. “The primary secondary transition marks a clear break where children feel like they’re moving out of childhood and into adolescence.”

Sue Cowley, an experienced teacher, writer and presenter, says she saw the benefit in her own children of being made to cope with a change in environment. “It’s those transitions from one setting to another that, although they’re hard, has created in them both an ability to cope with change but also has enabled them to grow personally.”

Difficult transitions

There are other concerns, too. For example, if a school’s philosophy and culture doesn’t work for an individual, some claim they will lose out throughout their entire education, rather than having a chance to try something new at secondary.

Cowley also points out that transitioning between schools gives children a chance to reinvent themselves. “Some kids start school and they get a reputation for being difficult. No matter how well the school deals with that, it’s inevitable that teachers have a reaction based on their prior knowledge of that child.”

Vainker acknowledges all these risks, but says they can be managed.

“There’s a big responsibility on heads to make sure their phase is distinctive,” he says. “When our pupils go into Year 6, their uniforms are going to change, they’ll be moving a floor up within the school, and they’ll have more privileges. We have the same transition when students go into Year 10, where they’re allowed to wear professional dress on a Friday.”

More difficult to manage is the potential negative effects of a broad age range of children co-existing in the same space, says Symonds. Her research reveals the risks around very young children seeing much older children and being influenced by their behaviours.

“This can be a problem if the older children exhibit behaviours that encourage the younger children to behave in ways that are not aligned with the culture of schooling, for example going out on the playing field and smoking a cigarette. The influence of children in that sense all depends on the culture of the school and the culture of the children within the school,” she says.

Featherstone says she tried to use this influence in a positive way by providing opportunities for older children to integrate with younger pupils.

Reach Academy does the same, enlisting older pupils to run extra-curricular clubs and brings pupils together through reading and mentoring programmes. Vainker estimates that in a normal week there are around half a dozen opportunities for this type of collaboration to happen.

Finally, on the curriculum point, most accept all-throughs should be beneficial, but there are still some issues.

One teacher in an all-through in the south of England claims that a joined up curriculum between the two phases is made difficult by “the accountability system forcing primaries to focus teaching in ways and on places that do not help the learning at secondary - the Sats do not necessarily create the students we need in Year 7”.

Key here is whether the ethos of the school is truly all-through, or whether it is in reality a secondary running a primary school, or vice versa.

One teacher who has worked in an all-through school for more than a decade on the primary side says it was clear where the power lay at her school.

“All new initiatives start in key stage 3 or 4 and we have to adapt to fit. Even when we have our ‘own’ systems that work, secondary is not interested,” says the teacher, who wishes to remain anonymous.

It’s a common complaint: one phase feeling inferior to the other. Getting around that issue is all down to headship.

Featherstone was acutely aware she was a secondary-trained head and did all she could to avoid any notion of bias towards her traditional phase. At Bridge, the headteacher is responsible for pupils across all phases, as are deputy and department leads. Each phase has a dedicated assistant head and another set of assistant heads lead vertically, including engagement and behaviour.

Vainker, too, has responsibility across the phases - and since Reach Academy is yet to appoint a primary head teacher, he also fulfils that role. In the future he envisages having a principal and two deputy heads that have responsibility across the phases and then a head in charge of each of the phases.

These structures don’t only have to make everyone feel equally valued, they are also the key to reaping all the potential benefits discussed above. Unfortunately, according to Liz Robinson, headteacher of Surrey Square Primary School, who has worked with future leadership participants in a number of all through settings, getting those structures right can be very difficult.

“All-throughs need to be led by somebody who understands that they need experts and that they’re not the expert in everything,” she says. “There is a risk that there is not a deep-enough level of understanding of the breadth of pedagogical expertise you need to teach four-year-olds and 16-year-olds. They are very different.”

Benefits unclear

Too different to merge in one school, under one system, under one head? At its core, that is the conundrum with all-through schools.

Can it work? The honest answer: we won’t know for some time. They’re complex models to get right, both practically and financially, but there are certainly potential benefits.

How those benefits are drawn out, though, are not yet clear - this is still a very small proportion of the overall schools sector and many of the schools are still working towards the point where they have results for students that have started in Reception and progressed to GCSE.

In the case of small schools such as Reach or King Solomon, separating the benefit of all-through from the benefit of small year groups is tough. And there is such diversity between the all-through models that you are likely to only get isolated examples of success at first - and then it will take time to replicate that.

So, until we get more evidence, this is likely to remain a niche area of education. The numbers will likely grow slowly thanks to free schools, but making a transition such as the one made by Bridge, from two schools to one, is extremely difficult and rare.

But what if, eventually, we do get a system of all-through that proves itself to work in different areas, in different contexts, on a big enough scale?

The worrying thing for the education sector is: if this does prove to be the most effective method of schooling, and a small-school model such as Reach’s does prove to be the most effective of the all-through systems, how would you begin to go about retrofitting an all-through model onto more than 24,000 neatly partitioned schools?

The answer currently is that this would be impossible. But if the case for all-through becomes strong enough, that might not be an excuse parents will be willing to accept.

Nick Hughes is a freelance journalist

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters