‘Classroom communication relies on the ritual’

During the recent half-term break, when the tide of emails had been stemmed and the legions of books and past papers had held their fire for a week while they built up ammunition for a fresh onslaught, I found one of those short, quiet moments of reflection on what the hell it was that this job was all about.

These moments can sometimes be accompanied by mental emojis of Munch’s work The Scream, but on this occasion I was lucky enough for it to coincide with my coming across a short thread of tweets from an academic in New York that drew me back to an essay I’d read long ago but since forgotten: James Carey’s A Cultural Approach to Communication.

Much as it might sound like drying Dulux, this seminal bit of writing by perhaps the most important scholar of communication theory ever gave me what I needed to hear as I tried to build energy for the mad run-up to Easter: if teaching was anything, it was about communication, and if it was about communication, then - if Carey was right - it was less about delivering facts than the radical act of creating new worlds.

James Carey - sometimes known as Jim, but not to be confused with the comic actor with an outrageously stretchy face - was a pioneering theorist and media critic who taught journalism at Columbia University in the US. He died in 2006. In 1989, he published his most important work, Communication as Culture, which arose out of his Cultural Approach essay of 1975.

He begins by outlining what he calls the “transmission model” of communication, which is probably how people popularly view the act of teaching. “Our basic orientation to communication remains grounded,” he notes, “at the deepest roots of our thinking, in the idea of transmission: communication is a process whereby messages are transmitted and distributed in space. It is defined by terms such as ‘imparting’, ‘sending’, ‘transmitting’ or ‘giving information to others’. It is formed from a metaphor of geography or transportation.”

This feels familiar. What we do in the classroom is draw on our vast store of knowledge and, over a number of years, gradually transmit it to a class of students. After each lesson, we hope, they carry away brains that have more information in them than when said students ambled them through the door an hour earlier pickled in Diet Coke and fed on Wotsits.

This is, to a large extent, how our education system can seem calibrated. In public exams, we ask students to gently regurgitate what they have been fed, and hope that they have not simply passed it undigested. Though more nuanced in how it is presented to us, at the crudest level, our inspection framework still feels like a before-and-after weigh-in: a means of checking how effective we have been in handing over knowledge, or sneaking it into their bags without them knowing.

If this feels a less than fulfilling way of spending your day, that’s because it clearly would be. Teaching cannot only be governed by a “transmission” model, because - as Carey outlines in his historical overview of technologies of communication and their links to early models of monarchical power - this suggests a kind of intellectual imperialism: the teacher has all the power, and their students are mere vassals with no agency. They are being filled with facts and should be unquestioningly thankful for it. The teacher has no interest in them as people, nor in them as bodies who might wish to take these facts, reflect on them, exercise their own power and act.

No. Teaching has to be more than this, and this is the heart of Carey’s theory: all public forms of communication have a dimension beyond transmission, a dimension that Carey calls the “ritual model”.

Medium is the message

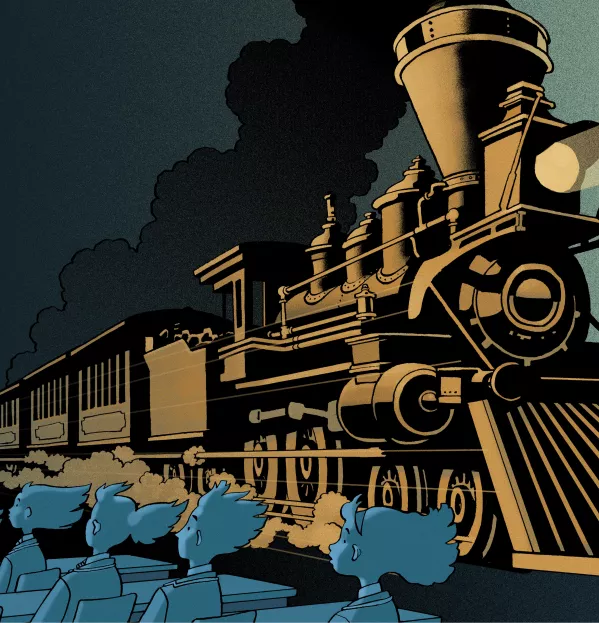

Looking back in history, Carey explores how technologies of communication and technologies of transport have been interconnected. What is interesting about the invention of the electric telegraph, he explains, is that for the first time, complex messages could travel faster than people, than horses, than trains. Communication became separated from the physical act of movement. Yet even prior to this, whenever people were exploiting new modes of transport, they were using this not simply to transmit information in new and more efficient ways, but to expand and build worlds.

The example Carey uses is of the evangelistic Protestant pioneers in the early US, who saw the expansion of the railroad as a means by which the kingdom of God might also be expanded. Later, these forward-thinkers jumped on the invention of the telegraph as divinely provided technology that would allow them to quickly build up new churches in far-off places. This wasn’t about the transmission of ideas, but the construction and transformation of religious communities in distant places.

Reflecting on this, Carey concludes that “the moral meaning of transportation was the establishment and extension of God’s kingdom on earth. The moral meaning of communication was the same.” (Moreover, when perceived morality is under threat, it is often the newfangled modes of communication - be they Snapchat, Luther’s printing press or trashy television - that are blamed for this moral collapse.)

So communication has a deeper dimension than simple transmission. Whenever we communicate, we are touching on ideas of ritual, on cultural codes and forms, and the means by which we communicate thus impact on the nature of the world that we are building. As Carey himself summarises it: “If the archetypal case of communication under a transmission view is the extension of messages across geography for the purpose of control, the archetypal case under a ritual view is the sacred ceremony that draws persons together in fellowship and commonality. [It is about] the construction and maintenance of an ordered, meaningful cultural world.”

Wary of getting mired in too much dry theory, Carey then works to root his ideas in some real-world practice, which he does so by asking his readers to think about reading a newspaper. This, he argues, is something of a ceremony akin to attending mass. Why? Because in church, nothing new is necessarily learned - there is no new information transmitted - but a particular view of the world becomes more solidified.

This may seem a little far-fetched, expressing consumption of “mass media” in terms of attending mass, but one only needs to observe the quasi-religious devotion that so many offer their communication devices now to see that Carey was absolutely right. Scrolling through countless posts on Instagram or Facebook is not about gaining new facts. It is communication as community, a technology that purports to build fellowship.

So what does this mean for the classroom? In his essay, Carey actually speaks directly to the question of teaching. “Lest someone think this obscure,” he writes, “allow me to illustrate with an example … Let us suppose one had to teach a child of six or seven how to get from home to school. There are a number of ways that this could be done, that this communication could be achieved. Firstly, the child could be asked to use trial and error. Or they could follow the example of an adult showing them the way, or someone could draw them a map, teach them the directions in song or in dance.”

Carey’s point is that the information about how to move in space from home to school can be represented using lines on a page or sounds in the air or dance movements. These are all different symbolic forms - visual, oral and kinaesthetic - which are used to represent the physical data of how to move from this space to another space. Because the shared meaning of these symbols is absolutely bound to culture, teaching-as-communication is always about the ritual model, about the selection of symbols and the slow process of building their shared meaning through time.

Pure transmission of information is a myth; whenever something has to be communicated, there has to be a world built through cultural forms to facilitate this. As Carey puts it: “There is more than a verbal tie between the words ‘common’, ‘community’ and ‘communication’. Men [sic] live in a community in virtue of the things which they have in common; and communication is the way in which they come to possess things in common.”

To place this more directly into our shared context: we live in a community in virtue of the things we have in common, and teaching is the way in which we come to possess things in common.

Teaching as a sterile transmission of information has nothing attractive about it. A robot could do it and, if this is the model of education that we see invested in, it won’t be long before robots are doing it.

But if, against this, we see ourselves as engaged in the ritual model of communication - which Carey insists that we must - then teaching is about the forming, sustaining and reforming of community. It is an active and evolving conversation about the things we feel we should possess in common, brought about through the careful, culturally sensitive selection of symbolic forms. Moving from transmission to ritual, suddenly, this is a job that is a little more interesting, a whole lot more attractive to brilliant communicators and those with an interest in the grassroots of politics. The stakes are suddenly higher, and yet the importance of endless assessments of how many facts have been transmitted suddenly feels correctly diminished. Yes, you can come and observe a single lesson or take a snapshot of what ink is in some books, but I am creating worlds here, engaged in forming future communities, so you might need to stay a while longer, get to know them and me better before making your judgements.

Yet, as Carey concludes his essay, he sounds a word of warning, one that we in education must listen to with sharp ears. The model of communication to which we choose to subscribe - consciously or unconsciously - will inexorably impact the kind of world that we will, over time, end up building.

If we allow our education system to be built around a transmission model, then what schools build will be students who are passive consumers, to whom teaching is done, for whom there is no hunger for enquiry or sense of self-discovery and shared communal discourse. It is my fear that this is precisely the kind of world that a high-turnover, relationally impoverished, low-paid schooling system generates, one that is convenient for those in power because it does not create students who will speak truth to it.

But in the age of student-led climate protests, my hope is that there remains a critical mass of teachers prepared to stand firm in the face of these pressures, defy the tick-box managers, inspire their students through ritual forms and build worlds in their classrooms.

For sure, there is no other way to survive in this profession. If you are in the room to transmit like a robot, you’ll soon run your batteries down and be replaced by one. But if your communication is based on community and commonality, on a rich sense of ritual and the powerful use of cultural symbols, you might just have fire enough to last a whole career, and no AI will ever get close to matching you.

Kester Brewin teaches maths in south-east London

This article originally appeared in the 29 March 2019 issue under the headline “Making communication ritual rich”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters