Could we stop and think instead of rushing in?

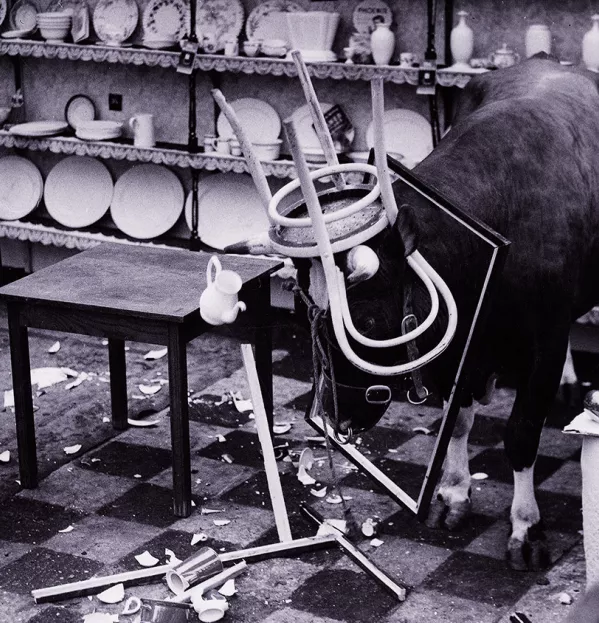

Something must be done. If there were a single sentence to sum up the past few years of Scottish education, that would be it.

It doesn’t even much matter what that thing is, as long as there is some of it and it is being done. Don’t worry too much about developing a proper understanding of the problems, and under no circumstances ask if any given something is the right something: it isn’t detail that matters, just action. Just doing something.

Perhaps it was always this way, but I’m not so sure. I’ve written a chapter on schooling for a new book examining the way Scotland has changed since the restoration of its Parliament 20 years ago. While looking back over this period, what struck me most was the sense of acceleration throughout the past 20 years, with policymaking seeming to shift from a relatively slow and often collaborative process to one characterised by knee-jerk, panic-stricken action.

For example, the environment in which the “national debate on education” took place in 2002 - paving the way for Curriculum for Excellence (CfE) - feels a million miles away from the one we now operate in. And I think it’s getting worse.

Our current cycle of panic-policy-panic can be traced back to 18 August 2015, when first minister Nicola Sturgeon demanded that her government be judged on its record of improving Scottish education. In delivering her speech at Wester Hailes Education Centre in Edinburgh, and attempting to align educational progress with electoral cycles, Sturgeon not only revealed a fundamental misunderstanding of how education works but also ensured that Scotland’s school system would become more politicised than ever before.

Since then, the announcements have come thick and fast.

‘Poisonous and shambolic’

We’ve had the imposition of standardised testing and the promise - swiftly abandoned - that the test data would be published on a school-by-school basis, despite the fact that this would only end one way: with the creation, official or otherwise, of poisonous school league tables. The policy has been shambolic from start to finish, with the most recent developments including a Holyrood defeat for the SNP government over P1 tests and, in an act of desperation, the subsequent setting up of an independent review into those tests.

There was the “definitive guidance” on teacher workload in 2016, which ultimately amounted to little more than a letter from education secretary John Swinney.

We’ve also had the wildly ill-advised dalliance with Teach First in 2017, which, after all the headaches and secrecy, ended with the fast-track teacher-training organisation withdrawing from a tendering process that it had, remarkably, both helped to initiate and attempted to bypass.

The government has come up with CfE “benchmarks” that - and this really is quite a feat - have had the effect of making curricular documentation and expectations even less clear than was previously the case. The removal of unit assessments in the senior phase was so badly handled that it ended up increasing workload through changes to final assessments, some of which now require teenagers to take exams that are longer than those I sat in university.

One especially large shift was the rebranding of England’s pupil premium - north of the border, we call it Pupil Equity Funding - meaning that huge amounts of money is now being funnelled directly to schools to enable them to “close the attainment gap”. This policy looks great on the surface, but many schools have struggled to use the money (around 40 per cent of last year’s allocation, amounting to nearly £50 million, wasn’t spent during the intended period). Councils, which actually deliver education services, have faced ongoing cuts to their core funding. This has put a massive strain on the system as a whole. To make matters worse, it remains all but impossible to find out where much of the cash has actually gone.

And in June, we watched the government suffer the humiliation of having to withdraw its much-hyped Education Bill, which was supposed to enable allegedly crucial structural reforms in Scottish education.

These past few years have featured a seemingly endless slew of dodgy ideas and bad decisions as desperate ministers have clutched at pretty much any available straw. This being the case, is it really any wonder that education is seen as a key area of weakness for the government?

Teachers know that rapid-fire gimmicks are no substitute for careful, long-term and very hard work. Any educator worth their salt realises that the serious job of improving our students’ lives is slow, frustratingly non-linear and not in any way suitable for a catchy press release or choreographed interview. There are no easy answers inside classrooms, so it really shouldn’t come as any surprise that quick fixes aren’t of much use, or interest, to us, even if they sometimes seem to be all that matters to politicians.

So, for 2019, I have this one request: I know it’s asking a lot, but could we please, for all our sakes, just stop and think for a bit?

Could we maybe get through a few months without thrashing out another godawful “reform” ? Could we consider the whole picture before we start throwing hundreds of millions of pounds at a problem in the vague hope that some of it might stick? Above all, could we please remember that it’s not our time we’re wasting - it’s our children’s.

James McEnaney is a journalist, FE lecturer and former schoolteacher

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters