How to help pupils make better decisions

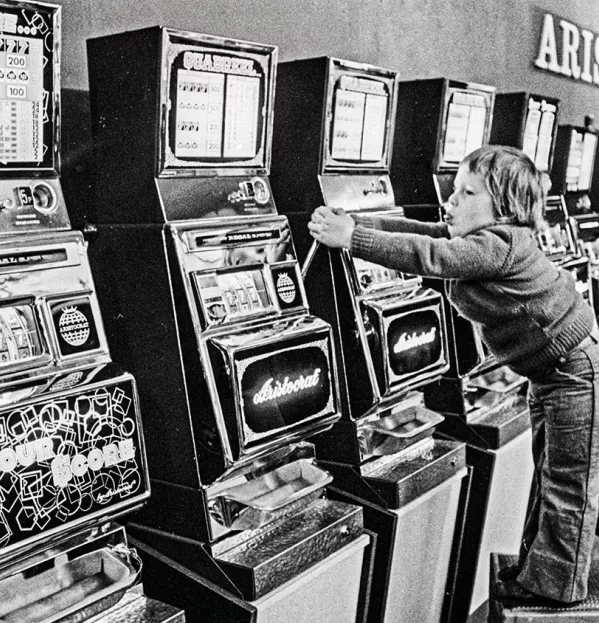

Many a teacher has warned a pupil that they could be “gambling with their future” because of poor decision making, but few would think to ask an actual gambler how to ensure that the odds were in their pupil’s favour. After all, the house always wins, and gambling is usually something warned against in PSHE (personal, social and health education) lessons rather than encouraged as a model for honing cognitive processes.

And yet, former professional poker player Annie Duke believes such a move would make perfect sense. Before turning her hand to professional card playing, winning more than $4 million (£2.9 million) from poker tournaments, she studied cognitive psychology at the University of Pennsylvania.

She has since combined this knowledge with her poker expertise to embark on a post-gambling circuit career as a consultant specialising in decision making. And she thinks she can help teachers help themselves and the young people they teach to make better decisions.

Duke says there are a lot of similarities between the decisions made during a game of poker and the type of decisions that we make in our daily lives.

“There’s a lot of hidden information [when you play poker],” she explains. “Obviously, you can’t see your opponent’s cards and you can’t know what they’re thinking. There’s also a lot of influence of luck on the way that things turn out. It’s a very noisy system and trying to extract signals from it is just really hard.

“All that hidden information and luck make it really easy for cognitive bias to take hold because, in the short run, why you might win or lose a hand isn’t always immediately obvious. It’s hard to tell whether you’re losing because you’re playing poorly or because you’re getting unlucky. Maybe you’re winning because you’re getting lucky or maybe you’re winning because you’re playing well.”

The same is often true for our everyday decisions. We frequently make choices without the full knowledge of consequences or the bias that might be at play. We are also often easily seduced into believing that success comes through what we have done rather than luck (something every teacher will recognise in their pupils, no doubt).

What gamblers can teach teachers about decision making

So, Duke began developing a decision-making approach that she believes should help everyone make better calls, and it soon became clear that this had educational applications. As a result, in 2014 she co-founded the Alliance for Decision Education, a non-profit organisation whose mission is to “improve lives by empowering students through decision-skills education”.

The aim of the organisation is to empower teachers, school administrators and policymakers to bring “decision education” to every middle- and high-school student, and enable younger people to make better decisions. Essentially, she thinks we should teach decision making.

So, what sort of approach has all that poker and research produced?

The first thing teachers and pupils need to realise, Duke says, is that most people approach decision making in completely the wrong way.

“If you ask people to describe their decision-making process, you would get descriptions that are all over the map,” she says. “Some people say ‘I use my gut’. Some people say ‘I make a pros and cons list’. Some people are the ‘I need a lot of consensus’ type people, so [they] ask a billion opinions, or need 100 per cent of the people in the room to agree. And some people are endless researchers.

“But the problem, for most people, is that they don’t have a consistent process and when we look at what goes on with people, a lot of decision making is pretty automatic.”

Just having this conversation with colleagues or pupils can be invaluable for blowing up the myth that we usually have a good decision-making process and nothing needs to change. For most of us, we definitely do need to change.

The second step is to understand that there are two approaches to making a decision - reflexive or deliberative.

“Most of the decisions that we make are reflexive, meaning they’re kind of fast and frugal,” she explains. “Our ancestors evolved in an environment where there was a lot of scarcity and groups were never bigger than 300 - usually they were smaller than that.

“There were lots of dangers around the corner and the people who were more likely to reproduce were the ones who just survived the day. So, what that means is that a lot of our reactions are like, ‘OK, let me just figure out what a shortcut is to get to something that will let me survive’.”

Shortcuts, as we all know, rarely turn out to be as effective or successful as taking time over something. There is always a cost.

Deliberative decision making, meanwhile, is a weighing of all the options. However, this can go awry, too. She cites the example of people who use pros and cons lists.

“We tend to think of binaries when we’re trying to make a decision,” says Duke. “We don’t say, ‘Here are all the different ways that things could turn out and here’s the likelihood that those things are going to happen’. We try to figure out ‘What is the thing that’s going to happen?’ Well, that’s impossible. And then, in retrospect, when you get an outcome that’s bad, you immediately think you made a mistake. We aren’t really equipped to think ‘probabilistically’, which is about really thinking about what’s going to happen in the future.”

When to hold, when to fold

So, once you are sure you understand where you have been going wrong, how do you get going again in the right way?

Effective decision making has a few key elements, she argues, and they are easily adopted by pupils and adults alike.

The first is to understand that decisions are not about finding certainty but weighing probability: like any good gambler, it is about working out the chance of any possible result.

People have to understand “that a decision is a prediction about the future and try to actually think about what the future might look like, given the decision that you’re thinking about”, she says.

Too often, we talk about right or wrong decisions when, actually, there are so many variables that we are really dealing with best guesses. As soon as you get into that mindset, Duke believes, we can make better-informed decisions.

The second part of the process is to realise that any decision you make is informed by your beliefs.

“Your beliefs sit at the foundation of your decisions so you also have to think, ‘How can I improve the quality of the things that I believe?’” she says.

She cites the example of recruitment. A headteacher might think they’re an amazing recruiter and that, 90 per cent of the time, their hires work out. However, the statistics suggest that new hires work out only 50 per cent of the time. The likelihood is that the headteacher’s beliefs are getting in the way of sensible decision making.

To guard against this, Duke says you always need to test your belief. What leads you to believe it and what suggests it is untrue? One way to expose any issues is to ask for a second opinion.

In the example above, she suggests the headteacher should get a second opinion from a colleague when hiring someone. She also says that, rather than tell the colleague that they’re really impressed by the job candidate and think they would be ideal for the job, which would create a bias, they should simply hand over their CV and ask the colleague to fill in a feedback form directly after interviewing the candidate.

A third component is to consider any decision against key goals: what is the end point you are seeking through this decision?

“Imagine, what are the different ways that a decision could turn out and how much does that advance me towards or away from my goals?” says Duke.

For example, if a student wishes to get on to a college course and needs certain grades, teaching that student to understand how each decision they make impacts that end goal may result in better decision making.

She believes it’s a case of “thinking about, ‘What are the outcomes that could occur and how likely are those to happen?’ And then you can scan those and start to see what’s the good and bad that comes from it. How likely is the good and bad? Do I think that this is going to be worthwhile for me to go ahead and do?”

Duke believes that teaching these techniques to children and, indeed, to adults could make a major difference to them in many areas of their lives, and she says that today, it is increasingly important that we arm people with the skills to make better decisions because we live in an age of information overload, which makes it increasingly difficult for people to figure out what’s true, what’s signal and what’s noise.

“I want people to have a really good decision process. I want them to understand that the world isn’t guaranteed to turn out one way and that, when you make a decision, you’re never going to know exactly how things are going to turn out,” she says.

“The more that you can see the different paths that the future might take, the better your decision making is going to be.”

Simon Creasey is a freelance writer

This article originally appeared in the 9 July 2021 issue under the headline “Tes focus on...Helping pupils make better decisions”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters