Child obesity: Why has the situation got so bad?

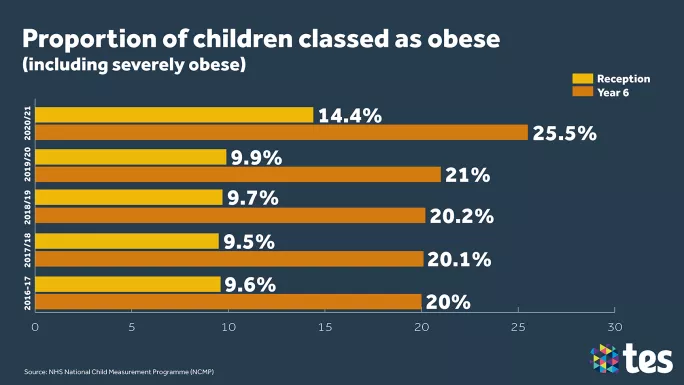

A quarter of all Year 6 pupils (25.5 per cent) and almost a sixth of all Reception-aged pupils (14.4 per cent) are obese.

And within these figures, 6.3 per cent of Year 6 children and 4.7 per cent of Reception-aged children are classed as “severely obese”.

These figures, taken from the NHS National Child Measurement Programme (NCMP) for 2020-2021, perhaps need to be read twice for you fully appreciate the stark reality.

It’s no wonder that Professor Stephen Powis, NHS England’s national medical director, called them “frankly disturbing”, while Dr Max Davie, officer for health improvement at the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, described the rise as “alarming”.

Furthermore, as is often the case with issues affecting children, those from more deprived areas are impacted the most:

- For Reception children, 20.3 per cent in the most deprived areas were obese, compared with 7.8 per cent of those living in the least deprived areas.

- For Year 6 children, 33.8 per cent living in the most deprived areas were obese, compared with 14.3 per cent of those living in the least deprived areas.

Despite the shocking nature of these figures, the reality is that they are not a huge surprise.

The last NHS NCMP for the 2019-2020 cohort revealed obesity rates of 21 per cent for Year 6 pupils and 9.9 percent for Reception pupils, and many warned at the time that the situation would get worse when the impact of the second, winter lockdown was added - exactly as has happened.

But why has obesity increased quite so much over the past 18 months? It appears the reason is twofold: the first, and most obvious, reason is a lack of physical activity.

How Covid lockdowns have affected child obesity

For example, a survey of almost 1,000 UK parents by Premier Education, a firm that provides sports and physical activities to primary schools, found that 63 per cent of children did less physical activity during lockdown than before the pandemic.

Furthermore, 82 per cent of the parents surveyed said their children had less than the recommended 60 minutes of physical activity per day.

David Batch, CEO of Premier Education told Tes that a big cause of this was the almost complete halt to all extracurricular activities and after-school clubs. “We saw a huge drop in extracurricular provision because of the guidance to schools telling them to stop doing these activities,” he said.

“Before the pandemic, we would have children often doing something with us once or twice a week but that stopped and for many, it meant their only chance for some physical activity had now gone.”

What’s more, despite many extracurricular activities and clubs now being back up and running, it seems many children have not returned. PE teacher Jack Wildsmith says he has seen “a reduced interest in team sports” from pupils, despite many taking part in swimming, rugby or hockey pre-pandemic.

He says the reasons are unclear but the loss of regular participation in these sports may well have reduced children’s desire to take part in sports and exercise.

This links with an issue that Batch says he has heard of anecdotally from across the organisation’s 1,200-strong team of staff in schools: since pupils have returned to school, many of the “skills” needed to take part in sport have diminished.

“We are seeing quite a lot of behaviour changes among children with reports of children finding it harder to collaborate, to work together, that their perseverance has dropped,” he said, noting that this may, in turn, make pupils reticent to take part in activities.

Certainly, the obesity data would back this up and it underlines just how impactful the loss of time in school to exercise, run around and have fun has been.

Food for thought

However, what appears to have made this situation even worse is a second equally important problem: poor diets.

Indeed, research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies showed that the average home was consuming more calories during the first lockdown than before the pandemic.

Kate Smith, associate director at the IFS and who was involved in the report mentioned, says: “We saw all households increasing their calorie intake, with takeaways being consumed twice as much as the year before. Even if you offset this against not eating in restaurants, it was still a higher calorie intake.”

The fact that this happened alongside the loss of physical exercise meant the impact was severe.

“Even without any changes in physical exercise, people were consuming more calories but if you combine that with being sedentary, with not being in school or not able to get out as much, it makes [obesity rates rising] unsurprising - although the levels of it are quite shocking,” Smith told Tes.

Although the report that she draws these insights from did not cover the 2021 lockdown, Smith says it seems reasonable to imagine that the same trends played out - or possibly were even worse, given it was winter and getting outside for exercise was even harder.

For teachers, this is no surprise, with many witnessing very poor diets for their youngest learners - even before the pandemic. For instance, one headteacher, speaking anonymously, described some “shocking scenarios” of the food being given to children by their parents.

“A parent once tried to bring in a McDonald’s for their child’s packed lunch. Another nursery child had six mini Swiss rolls for her lunch and nothing else,” they say.

They add that while they do share guidance for parents on healthy lunchboxes, “it seems that more needs to be done” and they are thinking about bringing back some of the healthy school initiatives to curb this issue, given what the latest obesity data reveals.

A long time to be inactive

Put these two issues together and it becomes clear why the obesity rate has risen so dramatically - especially when we take into account the length of the lockdowns and how long children were deprived of exercise opportunities and were likely having poor diets.

For example, Batch notes that prior research has shown that the six-week summer holidays alone can often reduce a child’s cardiovascular gains made during an entire school year by as much as 80 per cent.

“It’s no surprise that an even longer period without the chance to exercise has had such a big impact,” he adds.

All this has had a clear effect on children’s health, which teachers have witnessed first-hand.

Wildsmith says it is clear that there has been “a rise in the amount of children who cannot remain physically active for a prolonged period of time” since returning, while Kulvarn Atwal, executive headteacher of two large primary schools in the London Borough of Redbridge, is seeing pupils who are “less fit and more overweight”.

These two views will no doubt be echoed by teachers across the country. And, given the scale of the issue, Atwal says schools should be given funding to help improve pupil fitness because of the potential “long-term impact on the health of our children and young people”.

Calls for extra school funding

A call for funding has also been made by Tiffnie Harris, primary and data specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), who said: “Government action to resolve long-standing issues with sports premium funding would be a good start.

“Schools cherish this money and use it to provide the physical activity that children need, but this is currently allocated hand-to-mouth by government, and leaders have no certainty it is going to arrive at all.”

Meanwhile, Sharon White, head of the School and Public Health Nurses Association (Saphna), says more should be done to utilise school nurses to tackle the problem.

“School nurses [can], with the right resource, identify [obesity issues] early, assess and offer early help and brief intervention supporting children and their families,” she says.

“They can support schools in their health-related policies and practice ranging from catering through to healthy schools awards.”

However, she says a “disinvestment” in school nurses is reducing the opportunity for this to happen - and it also deprives children of a chance to speak to someone about issues they may be suffering from that could exacerbate an unhealthy lifestyle.

One headteacher, speaking anonymously, says the loss of access to medical professionals in schools also has the effect of making teachers uneasy about potentially raising the issue with parents.

“[Teachers] find it difficult to confront weight issues directly, because they feel that they are not qualified to do so in the way that a nurse or doctor might be,” they say.

Getting active

Despite the benefits that more funding in this area could offer, it seems unlikely anything will be forthcoming, given that the government could not find the sum of money it was told it need for academic catch-up efforts - even though it has repeatedly claimed this is a priority.

However, this is not to say nothing is being done, with the NHS announcing a pilot of 15 specialist clinics to work with around 1,000 children a year to tackle this issue.

This could involve the creation of tailored plans for a child on how to help them lose weight. NHS England told Tes this work may involve schools if required, although that would be on a case-by-case basis so there is no detail on what, if anything, schools may have to do.

Overall, it seems that if schools are to play a part in tackling this issue, they will have to use their own initiative and ideas to get it done - something many are already doing.

For example, Wildsmith says that, since returning to school, he and his fellow staff have had a big focus on fitness - with cross-country running used in particular - while Atwal also says his schools have made time for physical activity by getting extracurricular clubs back up and running and offering additional swimming lessons; “We’re also encouraging children to walk to school,” he adds.

But what if - as we have heard - children are not enthused by sports in the same way they were before the pandemic?

Batch says that one idea that can work is to try more alternative sports: archery and fencing are two that his company provides that prove popular for this.

“Sports like that are good because it’s usually the case that no one has done it so there is no perception of someone being better than someone else, and it’s more just a chance to try something out,” he says.

Meanwhile, Wildsmith adds that it is important to try and get parents on board to get them to “remind their kids of the enjoyment factor of sport”: “I would encourage all schools to have a larger interaction with parents to keep pushing them to get their children active again,” he adds.

Pushy pupils and pester power

Sue Wilkinson, chief executive of the Association for Physical Education, agrees that engaging parents is key.

She suggests that one way PE teachers could do this is by encouraging younger pupils to take part in easy activities at school that they can then “pester” their parents to do at home: such as going for walk to collect leaves or conkers or going out to jump in puddles in the rain: “The key is getting pupils to want to do something active and, ideally, getting parents involved, too,” says Wilkinson.

She adds that it could also be worth schools sharing activities for parents and pupils to try and promote them on the school website or via newsletters.

“It could be a case of doing a bit of research and finding things in the local area that are free or under £5 to take part in, so it’s accessible to all and making people aware of what else is out there,” she says, adding: “Schools can’t do all this on their own - it will need a joined-up approach.”

Furthermore, the Association for Physical Education also wants schools to feel empowered to make physical activity a central pillar of school life, with the associated benefits this can bring - not just to tackle issues like obesity but also to improve wellbeing and academic outcomes.

To demonstrate how this could work, the organisation recently launched an action research pilot with United Learning that will involve around 20 schools, both primary and secondary, placing PE as a core subject in the curriculum alongside maths, English and science.

Sir Jon Coles, chief executive of United Learning, said this will underline the importance of physical activity for a child and ensure that they receive an “an enriching education” to help them lead “happy, healthy and successful lives”.

The results of this initiative may not be seen for a while but it could provide some interesting insights and ideas for others to consider as part of any wider health and fitness efforts in schools.

Harris agrees that embedding an appreciation of healthy living into school life is now vital, given the scale of the problem that the NHS data has laid bare.

“These issues need to be addressed urgently because if we are not teaching children at primary age about the importance of being physically active and eating healthily, it is only going to lead to long-term health problems as they move through secondary school and into adulthood,” she says.

However, with winter upon us and children’s academic catch-up likely far higher up the agenda, it is unlikely that the government will provide a solution overnight and for many in education it may feel like another task on the ever-growing to-do list of what schools are supposed to solve.

Yet when the national medical director for NHS England says the scale of childhood obesity is now “a huge concern for the health of the nation”, it seems there may be little choice but for schools to do whatever they can to tackle this issue head-on.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters