Education inequalities: building a more equal system

Despite decades of policy focus on narrowing gaps between children from different backgrounds, our comprehensive review of educational inequalities shows that many inequalities remain stubbornly hard to shift.

The Covid-19 pandemic has increased inequalities further and the ongoing cost-of-living crisis will put more pressure on families and pupils - so building an education system that works for everyone is essential.

There is no single best solution to making education policy work. It is always a question of balance: between central oversight and local freedom, between depth of knowledge and breadth of exposure, between different groups of pupils, parents, teachers and schools.

These trade-offs are complicated and will continue to be revisited. But there are some principles that can help guide decision making on how to build a more equal education system.

Look at the education system as a whole

Inequalities in learning start early and grow throughout the schooling years.

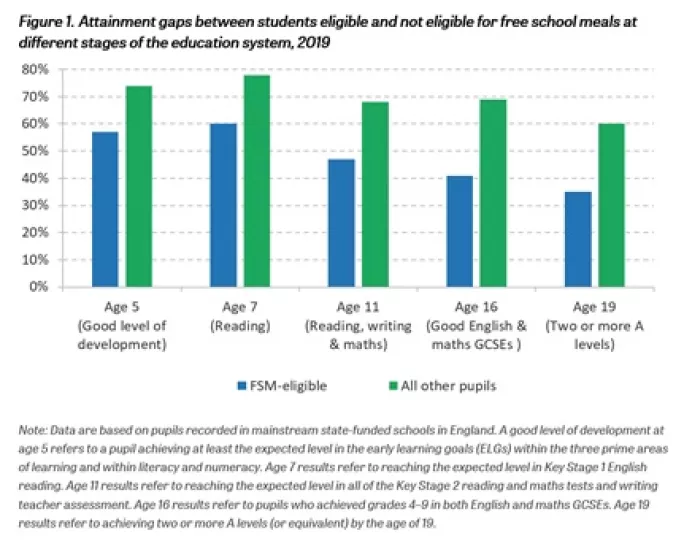

Even at the age of five, there are significant differences in attainment - only 57 per cent of children who are eligible for free school meals are assessed as having a good level of development compared with 74 per cent of children from better-off households.

These inequalities persist through primary school, into secondary school and beyond.

That means that building a more equal education system requires addressing what happens during the earliest years.

While there’s much still to learn about what works in the early years, we already have good evidence that some programmes (such as Sure Start children’s centres and the Family Nurse Partnership) reduce early inequalities in development.

Source: Figure 27, Farquharson, McNally and Tahir (2022).

But while early intervention is vital to achieving more equal outcomes, on its own it will not be enough. The effects of early interventions often fade and new inequalities can emerge around skills that are taught later in the education system.

Complementing early intervention with later support will help make the most of its potential.

That also means considering how policies affect the whole education system. A narrow curriculum at the end of school makes it harder to retrain later in life. Less generous funding for vocational education and a lack of second chances for adult learners creates higher stakes for young people taking their GCSEs.

More pressure on GCSE results shapes the decisions that schools, parents and pupils make in the years leading up to those exams.

Funding isn’t everything - but it is fundamental

Money matters for delivering an effective education system. The level and the distribution of resources influence the quality of education that schools, colleges and universities can offer, and who they target.

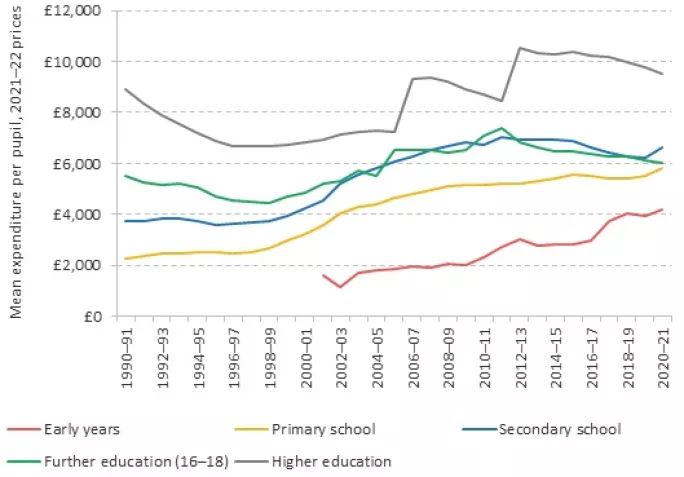

But after a dramatic rise during the 2000s, spending across all stages of the education system in England has gone through a long squeeze.

The per-pupil schools budget, though better protected than many other areas of spending, was 9 per cent lower in 2019-20 than it had been a decade earlier, and the cost-of-living crisis will eat away much of the budget increase that schools have received since then.

Meanwhile, further education institutions have been put under enormous financial strain by budgets that are slower to rise during “good times” and quicker to see cuts when the overall education budget falls.

Source: Figure 4, Farquharson, McNally and Tahir (2022).

Less generous funding affects the entire education system but it also has specific consequences for how equally resources are distributed.

The rate of pupil premium (targeted at roughly the most disadvantaged fifth of pupils) was frozen in cash terms between 2016 and 2020, making education funding less progressive than it was previously.

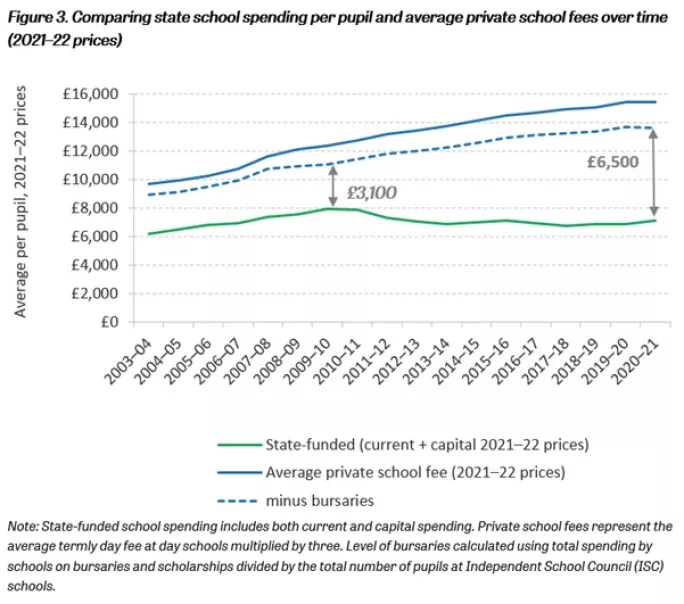

Despite the high levels of disadvantage among students in the further education sector, there is no FE version of pupil premium to target resources towards the more disadvantaged. Meanwhile, the resource gap between state schools and independent schools has more than doubled in the past decade.

Source: Figure 52, Farquharson, McNally and Tahir (2022).

Ultimately, schools and other providers of education need to have sufficient funding to produce high-quality education. There is increasingly clear evidence that spending really does matter for pupil achievement.

Recent evidence finds that higher school spending, on average, drives better test scores, graduation rates and continuation in post-compulsory education.

One study in England, for example, found that an extra £1,000 per primary pupil per year (roughly a 15 per cent uplift on current funding) resulted in four to five months of additional educational progress in age 11 tests, beyond what these students would otherwise have achieved.

In the longer term, policymakers need to be clear about what they are asking schools and further education institutions to do, and whether they are funding them adequately. At a minimum, this means that budgets need to account for additional responsibilities.

Many of the cuts to school spending through the 2010s were carried out through the back door, as local authority responsibilities were pushed down on to schools without a corresponding increase in funding.

More money will not always be the answer but substantially more responsibilities without more money is likely to cause problems elsewhere in the system.

Look beyond the education system, too

Inequalities in educational attainment shape people’s experiences throughout their lives - their chances of finding a job, their pay, their health, their criminality, even their happiness.

An education system that reinforces existing social inequalities - for example, by family background or by region - will hamper social mobility and perpetuate inequalities in the labour market and beyond.

But educational inequalities are a consequence as well as a cause of wider economic inequality. In an economy where the financial returns to “making it” in education are so high, there will always be pressure on parents to invest in helping their children to succeed. And in a society where the resources parents have to invest are so different, the education system will never be able to fully compensate for the vastly different experiences children have outside the school gates.

Therefore, if we are serious about addressing educational inequalities, it is not enough to look at the education system in isolation, we must also consider how we tackle broader societal inequalities.

The scale of the challenge

There is overwhelming evidence that the education system in England leaves too many young people behind.

Despite decades of policy attention, there has been little, if any, shift in the gaps in educational attainment between children from different backgrounds.

There is no straightforward, attractive route for young people who perform poorly at GCSE. And the adult education system has suffered from complicated funding rules and a shrinking pot of spending.

These challenges are set to become more acute. The Covid-19 pandemic put the education system under enormous strain, with significant learning loss overall and a huge increase in educational inequalities.

The cost-of-living crisis means that more children and young people will struggle with the educational disadvantages that come with poverty.

And changes to the labour market - from technological advances, adapting to new ways of working post-pandemic to the push towards net zero - mean that the education system will be called on to support workers of all ages to train and retrain for new jobs and industries.

Meeting these challenges will be essential for tackling inequality, and raising productivity and economic growth.

As past decades have shown, progress is often challenging and can be slow. But developing an education system that supports all children to reach their full potential is an enormous prize and one that should motivate all of us.

Christine Farquharson is a senior research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies and an author of the “Education inequalities” chapter of the IFS Deaton Review

Imran Tahir is a research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies and an author of the “Education inequalities” chapter of the IFS Deaton Review

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article