Education inequalities: second chances and vocational education

Compared to other countries, England does higher education well: almost half of young people in England now progress to university and, among the wider working-age population, almost 40 per cent have at least some form of tertiary education.

However, there are also millions of adults with poor qualifications and low levels of skills.

A quarter of working-age adults in England are not qualified up to upper-secondary level (A level or equivalent), which is above the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development average and over twice the level seen in Germany and the US. England is also almost unique in having seen no progress in literacy or numeracy skills in the last generation.

What’s more, these individuals tend to do significantly worse in the labour market. By the age of 40, the average UK employee qualified to GCSE level or below earns half as much as someone with a degree.

The poor outcomes for such a large share of the population have their roots in experiences during the schooling years: as we discussed previously, the school system can bake in failure from an early age. But addressing low levels of skill among the working-age population also requires us to understand the issues with post-16 education.

In our recent IFS research into education inequalities, we argue that our education system is held back by a lack of adequate second chances and an absence of clear pathways through vocational education.

This leaves many adults without the skills and qualifications they need to succeed.

Those who don’t do well the first time around rarely catch up

Achieving a pass grade in GCSE English and maths is an important benchmark. Yet, in last month’s GCSE results, nearly a quarter of 16-year-olds did not achieve at least a grade 4 in GCSE English. In maths, more than one in three pupils failed to meet this benchmark.

These pupils will be required to retake their English and maths exams, but many will not pass the next time around: less than 30 per cent of GCSE English and just 20 per cent of GCSE maths retakes were passed this year.

More broadly, nearly half of pupils who have not achieved at least five good GCSEs or equivalent by age 16 still have not obtained them by the age of 19. Even looking a decade out from their GCSEs, around 30 per cent of people who missed out on GCSEs the first time around had not earned these qualifications by age 26.

This educational stasis results in a high share of working-age adults without basic qualifications, which are crucial for success in the labour market. It also means a large share of the working-age population lacks foundational skills, hampering their productivity and restricting their options.

A ‘missing middle’ of advanced vocational learners

As well as a large number of adults with low qualifications, very few adults in the UK take advanced vocational qualifications like higher national diplomas, which have the potential to boost future earnings.

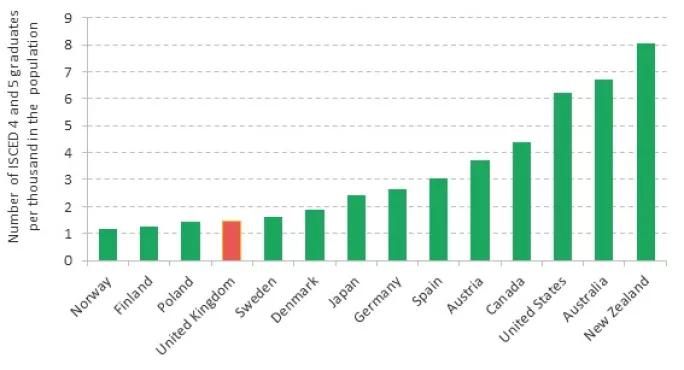

As Figure 1 illustrates, adults in the UK are almost half as likely as German adults, and a quarter as likely as American adults, to complete an advanced vocational qualification.

Figure 1. Number of first-time graduates from ISCED Level 4 and 5 programmes per thousand in the population, 2019

This results in a “missing middle” of advanced vocational qualifications, sandwiched between large numbers of people with degrees and large numbers not qualified up to upper-secondary level.

The lack of clear routes through post-16 education

Policy plays a role in hampering progress through the education system, affecting both the structure of the system and its funding.

The education system in England has long prioritised young people taking the well-worn path from GCSE to A level to university. The options for young people who do not earn good GCSEs at age 16 are limited and confusing, and there is often no obvious pathway from vocational qualifications at one level to the next.

Frequent policy changes also complicate matters; the introduction of T levels and higher technical qualifications (HTQs) are the latest examples. While reforms may bring benefits like a better-designed vocational education system, they are not costless: regular shake-ups make it difficult for both learners and employers to determine which qualifications are worth pursuing.

Funding and student finance inhibit access to post-16 education

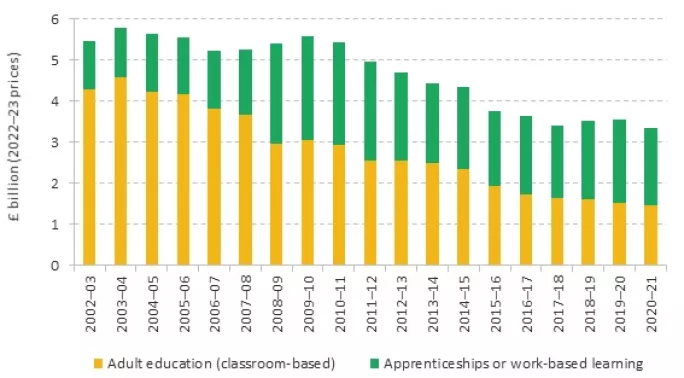

A crucial constraint on studying as an adult is access to funding. In Figure 2, we show the level of public spending on adult education and apprenticeships.

Figure 2. Total public spending on adult education and apprenticeships

In 2019-20, spending on adult education was nearly two-thirds lower in real terms than in 2003-04, and about 50 per cent lower than in 2009-10.

The decline was mainly driven by the removal of public funding from low-level classroom-based courses. Some of these courses had been found to have low returns for learners, but cutting back on them does make it more difficult for adults with few existing qualifications to access educational courses.

For advanced vocational qualifications, learners typically access government-backed loans to finance their studies. These are modelled on higher education student loans, but the lack of maintenance support means they have less favourable terms than those available to degree students.

The complexity of the vocational education system and a lack of adequate funding means that adults often cannot access the education and training they need, which limits the scope for existing educational gaps to be closed.

If we are serious about tackling inequalities and also boosting the productivity of the wider economy, it is essential that we ensure that the education system provides first-class vocational routes and the appropriate second chances.

Christine Farquharson is a senior research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies and an author of the Education inequalities chapter of the IFS’ Deaton Review.

Imran Tahir is a research economist at the Institute for Fiscal Studies and an author of the Education inequalities chapter of the IFS’ Deaton Review

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article