Closures and cuts: the population crisis about to hit schools

“This summer, I was forced to close a primary school…If we don’t act fast, more school closures will inevitably follow.”

That was the dramatic warning given last year to Nadhim Zahawi, when he was education secretary.

It came from Jasmine Ali, deputy leader and cabinet member for children, schools and education at Labour-run Southwark Council, in a letter that was also signed by another 11 education and children’s services council cabinet members from across London.

The issue that prompted this serious warning? A declining birth rate that meant keeping St John’s Walworth Primary School open was, as the report confirming the closure said, not viable because “significant falling pupil rolls place[d] irreversible pressure on the school budget”.

Falling birth rates: the impact on schools

As a result, 144 pupils and their families were left without a school and faced the rigmarole of finding a new one.

As Ali’s warning to Zahawi made clear, this was not just a one-off incident specific to a borough of London but an issue with national implications.

Fertility rate is the average number of children born to women during their reproductive years

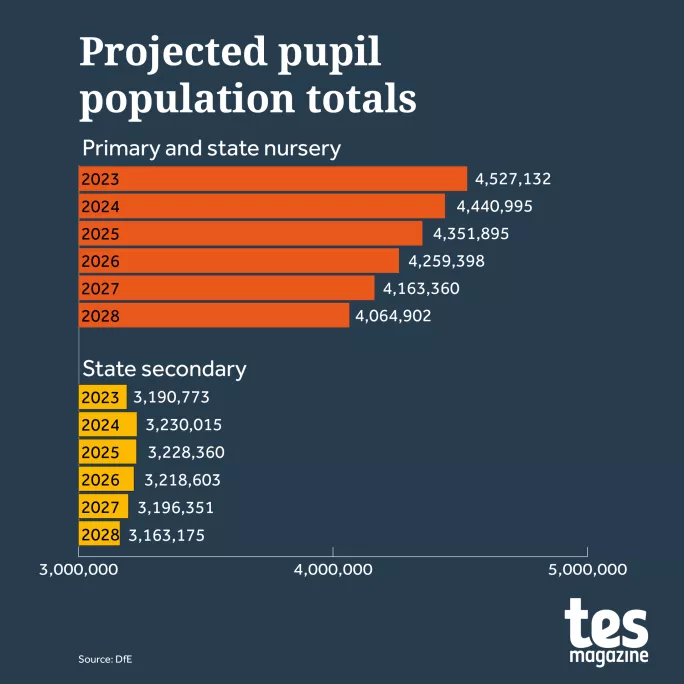

This decline in the birth rate will have a clear impact on pupil numbers for many years to come - as the Department for Education’s latest pupil number projection for England underlines.

It forecasts that there will be a total of 4,064,902 pupils in nursery and primary schools in 2028, down by 532,000 from the 2022 number of 4,597,370.

This issue will then feed into secondary schools - where the student population will already be in decline before that primary cohort even arrives.

“The population attending primary and nursery schools peaked in 2019 and the figures have been dropping since then…primarily due to the continued reductions in the birth numbers since 2013,” the DfE explains in its projections.

This matters in terms of school budgets because schools are funded on a per-pupil basis, and are expected to meet agreed published admissions numbers (PAN) to justify that funding.

“Pupil numbers drive by far the greatest part of school funding, and even many additional grants are headcount dependent,” explains Tomas Thurogood-Hyde, assistant CEO at Astrea Academy Trust, a group of 26 academies across South Yorkshire and Cambridgeshire.

“As rolls fall, so too will income.”

As such, a school’s financial viability will be threatened because while funding will be cut based on the fact that the PAN has to be reduced, other costs such as staffing, energy and other bills will remain.

It was this issue that forced Southwark Council to close a 156-year-old primary school - with many more schools still at risk, as Ali and the other London council cabinet members made clear in their letter.

“We have reached a critical stage where we are now asking the government to support us so that we can support the education of London’s children,” they wrote.

“Pupil numbers drive by far the greatest part of school funding”

Many other local authorities across England are increasingly aware of how the population decline will hit their schools.

Last year, a paper presented to councillors in Bradford said that monthly data from the local NHS trust showed “that the numbers of younger children living in the Bradford District is reducing”, and that PAN reductions resulting “in a total reduction of 1,910 primary school places have been agreed…since 2019”.

Also last year, Bury Council forecast that the falling birth rate would mean that the annual primary school pupil intake number would fall from 1,928 in 2022 to 1,719 in 2025, a decline that would “impact the sustainability and viability of individual schools”.

Drop in pupil numbers ‘will be painful’

Meanwhile, in June this year, it was reported that Somerset County Council had forecast that there will be 476 fewer primary-age pupils in the county by 2026 - a fall of 8.6 per cent on 2021 numbers.

A council officer told councillors at a meeting: “We are entering a period of numbers decline and this is almost certainly going to be very painful for the county, since it involves discussions about less money, about less staff and even about closing schools.”

It’s not just an issue in England. Scotland and Wales both have even lower fertility rates than England’s figure of 1.61 - at 1.37 and 1.49 respectively.

So, what is behind the drop?

“The decline in the birth rate since around 2010 is greatest at younger ages,” says Ann Berrington, professor of demography and social statistics at the University of Southampton and a member of the Office for National Statistics’ expert group for national population projections. She adds that women in their teens and twenties are opting to delay childbearing for much longer.

Reasons put forward for people delaying parenthood include: “economic insecurities in the labour market, especially for young people”; “housing insecurity” in terms of a shortage of social housing and increased costs of renting and buying; and the fact that “for a minority, there may also be concerns about the climate crisis, though for past years the evidence for the UK has been mixed”.

So, why is the rest of the UK faring even worse than England?

“No one has sufficiently accounted for why Scottish fertility is so much lower than England and Wales,” says Berrington - but factors could include the fact that Scotland has lower international migration and “the age profile of international migrants is often associated with childbearing”.

Schools and trusts are increasingly aware of the challenges - and they’re worried.

The long-term trend of a falling birth rate nationally makes it likely that there will be “a growing number of school mergers and closures across the country,” says Rowena Hackwood, chief executive of Astrea Academy Trust.

Furthermore, for trusts with wide geographical spreads, this is an issue being felt in numerous locations, as Cathie Paine, chief executive of REAch2 Academy Trust - the largest primary-only trust - explains.

“What we are typically seeing in the areas we work in is ‘sporadic’ periods of falling numbers, rather than a wider systemic issue of long-term overcapacity,” she says.

Schools forced into mergers

Paine can also foresee this leading to mergers - but she cautions that this is not a silver bullet. “While in areas where there does appear to be long-term overcapacity, merging schools might look like an easy answer, it is not straightforward and needs to be handled with great care and sensitivity,” she says.

The need for sensitivity relates to the fact that redundancies are inevitable if pupil numbers dip too far.

“If you are a two-form-entry school and 40 children enter Reception, you have to choose between paying for a financially inefficient number of teachers or mixing year groups in one class, which isn’t to their best educational benefit as we recover from the pandemic,” says Hackwood.

Greg Dempster, general secretary of Scottish primary school leaders’ body the AHDS, agrees. He says that the Scottish government has committed to increase teacher numbers over the coming period and many of those additional recruits are “expected to be in the primary sector”.

“Despite the reducing pupil population in primary schools, this element of the budget appears to be heading in the opposite direction,” he says.

“The impact on school funding could be devastating”

If this happens, and pupil funding decreases, Dempster questions whether other school staff roles will be protected.

In England, the recruitment of teachers is woefully under target but this won’t necessarily correlate with the gradual reduction in the number of teachers needed for a smaller pupil population, says Jack Worth, school workforce lead at the National Foundation for Educational Research.

“Falling birth rates will result in fewer pupils, which means that fewer teachers would be needed in the future, and this may help to reduce teacher supply challenges,” he tells Tes.

He notes, though, that waiting for pupil numbers to fall is not a viable strategy for addressing teacher shortages, given how long it will take for the impact of falling birth rates to be felt in the system.

“This change in the need for teachers would be seen in primary at first, and later in secondary, once those pupils reach secondary age,” says Worth.

“While it would eventually help ease the need for quite so many new teachers, which is less critical for primary as supply targets are usually met, this will not reduce the teacher supply problem at secondary level until many years in the future.”

This problem of a falling birth rate, of course, does not exist in isolation. For example, Brexit means that the number of international students that boosted school rolls has also declined, as Tom Campbell, interim chief executive of E-ACT, which runs 28 academies across England, acknowledges.

“When I was a headteacher 10 years ago, around 60 per cent of my secondary students were from Poland, Latvia, Lithuania and other Eastern European countries,” he says.

He adds that another pressure on student numbers is the fact that even more free schools are opening, often in areas where they are not required.

“The combination of these issues - birth rates, Brexit and free schools - is having a very real and very negative impact on pupil numbers,” says Campbell. “At a time when labour costs and energy price hikes are beginning to bite, together with inflation reducing our purchasing power, the impact on school funding could be devastating.”

What can schools do about the situation in the short term?

In Southwark, Ali successfully went to the Office of the Schools Adjudicator on behalf of 13 schools to have their PANs reduced, so they could maintain their level of funding despite falling numbers.

This worked for a short while but as the decline continued, the issue returned and led to the school closure cited earlier.

Collective action would be tricky, as different regions face a different level of challenge. There are “large regional differences” in fertility rates within England and Wales, says Berrington - a point made clear by this interactive ONS map:

For example, looking at four nearby areas in the North West, we can see that Manchester (1.4) has a lower rate than Salford (1.7), which has a lower rate than Wigan (1.8), which has a lower rate than Bolton (1.9). While for some it will be a major issue, others may fare better.

It’s worth noting here, though, that the government does make allowances for falling school rolls, with funding available for schools that are affected by this.

However, given the national scale of the population decline, Ali says this will be nowhere near what is required, while Thurogood-Hyde warns that the speed at which this funding can be received will be a problem when schools are under so much financial pressure.

“Mechanisms to secure additional funding on the basis of growing or declining numbers…are generally not quick or easy to obtain,” he notes.

“Schools will usually be expected to use their reserves to smooth the path, putting additional pressure on capital and contingency budgets already challenged by factors such as energy prices and unfunded pay increases.”

The need for government action

It is a complex problem, then, and for Ali this underlines why urgent action is needed to “plug this gap while we weather the storm and have the breathing space to work out what we are doing”.

“An immediate cash injection of £30.5 million is required to prevent the closure of these schools and significant additional sums will be necessary in order to save more schools from falling into deficit,” the letter from London council cabinet members said.

A longer-term solution that Ali and her colleagues proposed to the secretary of state would involve “a new schools funding formula that enables our schools to remain open with smaller class sizes”.

In short, schools should be funded as organisations, not by pupil numbers.

Campbell agrees that it would be good for the DfE “to consider alternatives to the ‘per-pupil’ funding formula”.

“Whether a school is at PAN or not, it still costs the same to heat the school, to keep the building open and safe,” he says. “Whether a class is full or not, it still needs a teacher at the front delivering. Schools simply do not have the facility to reduce costs in line with a reduction in income as a result of falling pupil numbers.”

James Bowen, director of policy at the NAHT school leaders’ union, also urges the government not to see the situation as a cost-saving exercise, saying instead that it should be seen as an “opportunity to do something really interesting and say, ‘Let’s try to at least maintain funding levels, but allowing smaller class sizes’”, or to increase investment in special educational needs and disabilities support.

“Whether a class is full or not, it still needs a teacher at the front delivering”

Hackwood says the issue of falling birth rates should be a focus for government not just from a funding point of view, but also from the perspective of how it will “feed into the government’s thinking about the deliberate design of a fully academised system” and the role trusts can play in this.

“We need to make sure that there is enough provision in each area, that it is sustainable and that there remains choice for parents,” she says. “This is not an easy task and will depend on collaboration between schools, trusts and local authorities.”

The DfE, it appears, isn’t ready to make any big changes, though. In response to all the above, a spokesperson said: “We continue to deliver year-on-year, real-terms per-pupil increases to school funding with a £7 billion cash increase in the core schools budget by 2024-25, compared with 2021-22.

“Our national funding formula distributes funding fairly, based on the needs of schools and their pupils. It is for local authorities to balance the supply and demand of school places, and school leaders to decide how to spend their budgets.”

For Ali, such a response seems deaf to the long-term impact that the decline in pupil populations will have and that cannot be ignored or avoided.

“I can’t understand why the government is not taking this seriously…we absolutely need to recognise this as a proper risk - it’s a national issue now,” she says.

John Morgan is a freelance writer. Additional reporting by Dan Worth

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters