Teachers want to influence education policy - so why ignore them?

The latest report on the working lives of teachers and leaders, which found that most have lower wellbeing than the wider adult population, makes for depressing reading.

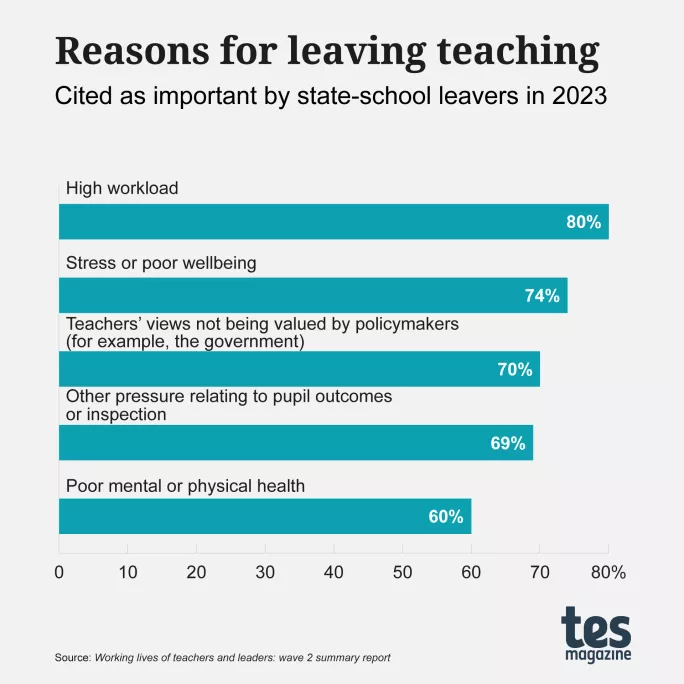

It is perhaps not surprising, though. It’s been 10 years since the Workload Challenge attempted to battle teachers’ excessive workload - yet clearly little has changed, considering that 80 per cent of teachers leaving the state sector now cite this as a reason.

Wellbeing remains a big issue - with 74 per cent of teachers leaving citing this as a reason. These problems are well known, alongside pay (cited by 39 per cent as a reason for leaving) and lack of opportunities for progression or promotion (cited by 29 per cent).

But one statistic that perhaps deserves a closer look is that 70 per cent of teachers leaving say one reason is that their views are not valued by policymakers.

This figure seem high. But if we look back at the way past governments have engaged with the profession, perhaps we should not be shocked.

After all, who can forget Chris Woodhead’s claim (when he became the first chief Inspector of Ofsted in 1995) that 15,000 teachers were incompetent? (The evidence for this statement he failed to produce).

Teachers feel like no one’s listening

Such unsubstantiated belligerence demotivated teachers and set the tone for everything that came in the following 30 years, not least because it piled on the stress of inspections conducted in such a negative spirit.

Sir Michael Wilshaw, as chief inspector, then railed against teachers leaving school on the bell as evidence of a lack of commitment.

More recently, former prime minister Liz Truss delivered a fierce criticism of her Leeds comprehensive, omitting the fact that it helped her get into an Oxbridge college.

Perhaps worst of all were the tactics of Michael Gove, who, as education secretary, labelled those opposed to his meddling in examination specifications as “The Blob”, thus caricaturing progressive teachers as woolly thinkers.

Of course, ministers regularly talk about their own favourite teachers and pay appropriate lip service to teachers when required - during exam season perhaps or during elections. But given the wider narrative from on high, it is no surprise that the sector feels unheard.

What’s more, a glance at various committees set up to investigate certain aspects of teaching shows why teachers feel overlooked - usually these are formed of researchers, influential headteachers, multi-academy trust leaders, the inspectorate and the exams regulator. Rarely is a classroom teacher featured.

Even the panel for the current review of curriculum and assessment does not feature a single subject association or teacher, despite the fact that whatever it proposes will directly impact classroom practice. Again, what message does that send?

The last time I can remember ordinary teachers being included was the Workload Challenge working groups investigating marking, data input and planning - back in 2014. I was a member myself.

It was certainly a rare privilege to be involved in the process of identifying the problems and considering recommendations. The fact that our joint classroom experience was listened to on a subject central to the wellbeing of the profession meant that solutions could be more workable.

Why this has not been repeated I don’t know, especially when there are clear benefits for teachers having a direct input into matters affecting them: their motivation is improved; they learn from the experiences; and they pass this on to colleagues, thereby increasing expertise within the system.

Tapping into teachers’ experience

Policymakers seem to forget that each graduate teacher has devoted four years and a lifetime of university debt to equip themselves for the role. For some reason they are regarded with suspicion, rather than as a valuable knowledge base to be used when required.

Labour has said it wants to reset the relationship between teachers and government.

Perhaps one way it could do this is to make sure that those who actually work in classrooms are featured more directly in discussions about new policy plans and initiatives.

After all, there is a world of difference between education as observed by those sitting at the top of the system and education as experienced by those at the chalkface.

Clearly teachers don’t feel heard - and that is something worth listening to.

Yvonne Williams has taught for more than 30 years, and was a member of the Department for Education Marking Policy Review Group, which looked at teacher workload in 2015-16

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article