More money not a fix for ‘drastically overworked’ teachers

It’s a statement so obviously and manifestly true that it should hardly need repeating, yet it does. Too many people within education and outside either forget it or wilfully choose to ignore it.

So here it goes: a school is only as good as the teachers that work there.

A slightly longer version goes a little like this: It doesn’t matter how much reforming and tinkering you do to the structure of a school system, or the assessment regime or the curriculum design; if the teachers are uninspired and burned out (or indeed absent), little else amounts to more than a hill of beans.

Flip this around and we can see it as a positive goal to aim for: if you have an inspired, respected, professional, developmentally oriented and motivated teacher workforce, everything else follows.

Yet this key fact is ignored in too many countries, too much of the time. The result? Desperate teacher shortages in all four corners of the world and creaking, underperforming schools.

A global issue

In the UK, the picture is bleak with many secondary subjects falling far below recruitment targets. It’s a similar tale in Europe where, across Germany, Hungary, Poland, Austria and France, more than 80,000 teaching positions remain unfilled.

This scenario is repeated in much of the anglosphere, most notably in Australia and the US, too.

The global south is no different. In much of Africa, which has the fastest-growing school-age population globally, teacher shortages are too common.

Many international organisations, like Unesco, the World Bank, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development and others, have been very clear about this challenge. We have made substantial progress during the last two decades to get more children to school and meet the United Nation’s sustainable development goal 4 on education.

However, this is not enough. We must overcome the learning crisis as well. Studies have shown that in many developing countries, only 12 to 23 per cent of the children who have been in school for at least seven years met minimum proficiency levels for maths and reading.

Being in school is not the same as learning, and learning outcomes are strongly connected to the availability of a qualified teacher workforce. Unesco Institute for Statistics estimation shows that there is a need for more than 69 million new teacher positions by 2030.

Pay is not the only solution

So, what to do? Many will, quite understandably, point to staffroom pay. Increase salaries, trade unions argue, and recruitment and retention follow in its wake. This is, of course, at least partly right.

Part of professional status and motivation does follow from making sure pay packets acknowledge and respect the workload and the vital role our teachers play in developing the future.

But I am not convinced that salary structure is the only answer to this problem. In my experience, teachers’ professional motivation, self-worth and, ultimately, the length of their service is also intimately tied to the professional conditions in which they work and how their career is developed.

I know this best via my experience in Finland, where I was minister for education. Well-educated teachers are always mentioned as a central explanation behind good learning outcomes.

I have had a habit of asking young students studying to become teachers why they have made that career choice.

So often I received the same answer: to have a job with a purpose and to have the autonomy to develop my own pedagogical solutions and professional competencies (teachers have substantial autonomy to find the best methods to reach the aims of education).

If teachers, who obviously won’t have chosen to go into the classroom to become rich, are given time to develop their practice, to think about and research their subject and their pedagogy, and are provided with high-quality professional development, then many positives flow from this.

The perils of workload overload

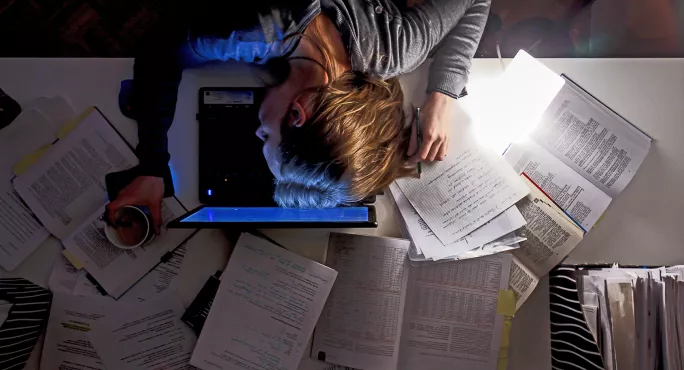

Too often around the world, teachers are drastically overworked, their time for professional reflection is minimal, and their professional development is sub-standard or even non-existent.

No wonder morale is at rock bottom, and thousands are quitting the classroom. Seeing and hearing this will hardly inspire others to enter the profession, or as career changers.

We can only do something about this global crisis if everyone in education stands up and commits to improving teachers’ professional lives.

This is why one of the strategic initiatives for the International Baccalaureate in the coming years is to invest in professional learning and the creation of a digital channel for professional development to better support teachers - IB teachers and, hopefully, in the future, non-IB teachers.

I hope others follow suit. If everyone in education does their bit, ideally by working together and thinking not just about how to recruit teachers but also how to foster, develop and encourage them, through the support of the community where they are working, then slowly, we might begin to see the recruitment and retention challenges around the world begin to ease.

And then - sure as day follows night - outcomes will begin to creep up for everyone. It is said that the temporal influence of a teacher reaches 100 years through the lives of their students.

Teacher professional development may not be politically sexy, but it is the missing ingredient in global education.

Olli-Pekka Heinonen is the director-general of the International Baccalaureate

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article