‘No, Ofsted - nude pictures aren’t just clumsy’

There’s been some turmoil in the past couple of days over comments made by Ofsted chief inspector Amanda Spielman to the Commons Education Select Committee.

Responding to questions about the recent Ofsted report on sexual harassment in schools, she acknowledged that the distribution of unsolicited sexual images is common among schoolchildren, but said that most of the girls she had consulted “laugh that off”. She added that girls would not want to be drawn into a formal safeguarding procedure over something they think is “contemptible”.

As you can imagine, edu-Twitter went wild. There was a flurry of outrage, calls for resignation and a corresponding, “Hey, kids make mistakes” lobby.

Ms Spielman has since clarified her comments, explaining that the girls she met choose not to report harassment because they worry about the “next steps”. As she pointed out, the key recommendation of the Ofsted review is for schools to assume sexual abuse is happening to their students whether they report it or not, and to create a culture that does not tolerate it.

Sex abuse in schools: Nude pictures are a safeguarding issue

However, her comments have reignited discussions about what is acceptable and whether sending naked selfies is a safeguarding issue.

For me, there’s no question about it. For a start, the distribution of indecent images of anyone under 18 is illegal under the Communications Act 2003, section 127. Repeated messages or requests for indecent pictures are also an infringement of the Protection from Harassment Act 1997.

Ms Spielman spoke of a “spectrum” of sexual offences, from the “truly evil and appalling” to the “clumsy explorations of emerging adolescent sexuality”.

Sending a naked selfie may well be a clumsy or misguided gesture, but that doesn’t make it OK. Any male of any age who sends an unrequested picture of his penis knows it’s not good manners; that’s why we have trousers. We can’t create and sustain a culture that does not tolerate sexual harassment if we write off illegal images - child pornography - as “clumsy”.

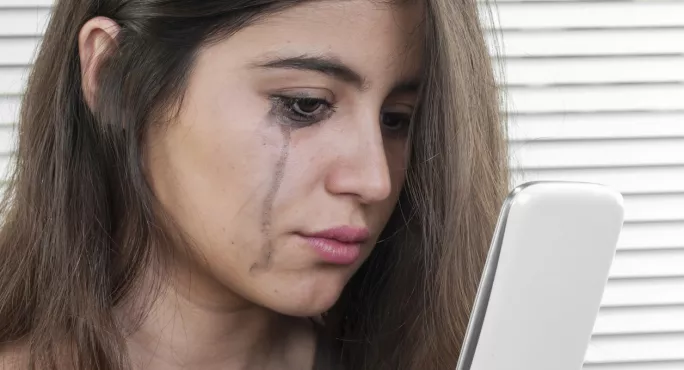

Teachers, and especially those of us who work in pastoral care, know that sexting is commonplace: that for every student weeping in our offices over a naked picture, there’s an entire cohort who’ve sent, received, passed on, asked for or been asked for indecent selfies.

It’s everywhere. Since the arrival of smartphones, it’s never been easier to take a picture of an engorged body part and send it on, either to another individual or, indeed, a global audience.

Again, that doesn’t make it OK. A quick flick through the diaries of Samuel Pepys reveals that it was an everyday occurrence for a 17th-century - and let’s face it, in all likelihood, 18th-, 19th- and probably 20th-century - gentleman to grope his female servants. The routine casual sexual assault was suffered in silence or, in some cases, laughed off.

But laughter doesn’t always signify acceptance. Laughter can cover embarrassment or fear; it can be the last resort of reluctant resignation. Our 21st-century students need to know that it’s fine to be unamused by unwanted sexual behaviour and that being upset is a proportionate response.

There’s a line in Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity where he describes his teenage protagonist’s encounter with a girl, where he uses “a degree of force that would have outraged and terrified an adult female”. It resonated when I first read it in the 1990s, and it’s echoed throughout the intervening decades.

Written well before the epidemic of dick pics, it illustrates the uncomfortable rite of passage endured by many young women: fighting off sexual advances that are either unwelcome or for which she is not ready. From our privileged position of age and status, we must not lose sight of what it is to be vulnerable.

If adults wouldn’t stand for it, why should teenagers?

Most adults have the power and wherewithal to seek recourse and protection. I cannot imagine for a second that any one of us would greet an unsolicited picture of a friend or colleague’s genitals with a chuckled “contemptible” and move on. There would be a degree, at least, of shock (slightly delayed if you’re anything like me - and, yes, this happens to everyone - while I find my reading glasses to check why a passing acquaintance should send me a photograph of what, at first glance, appears to be an unappetising chunk of charcuterie. I know. Laughing it off right here: the power of conditioning), discussions about how to deal with it and what to do if we encounter the sender face to face.

We’re right to be offended. But let’s remember, this is what some young people experience on a regular basis: receiving pictures they don’t want to see, often from someone they know, and then having to share a classroom with them. Adults wouldn’t stand for it - why should they?

Girls send pictures too, although, in my experience, these tend to have been requested by another student - usually, again in my experience, a boy. The risk of the images being shared is high. Once that “send” button is clicked, the picture is irretrievable.

I was once asked what advice I’d give to girls at key stage 4, and although my final official answer was a banal “believe in yourself”, what flashed through my mind was a banner unfurling with “stop posting pictures of your tits on Snapchat!” painted across it. Of all the tears I’ve mopped up over the past decade, the primary cause has been this very thing.

Our safeguarding procedures are there to protect recipient and sender. If we’re going to encourage students to trust us to deal with troubling matters, we need to make that clear. It’s not about judgement or demonisation.

Just as there’s a spectrum of offence, there’s a spectrum of response. There must be education about the gap between intention and impact; there must be support and reassurance if a student is unhappy or harassed.

We need to educate ourselves and understand the way in which technology has facilitated easy, immediate and public humiliation and manipulation. However, we must also be consistent, persistent: the normalisation of offensive acts contributes to rape culture - we have our work cut out to challenge it.

I’m sure that, over the next few days, Amanda Spielman will comment further on this issue; this difficult conversation must continue and evolve.

Sarah Ledger is an English teacher and director of learning for Year 11 at William Howard School in Brampton, Cumbria. She has been teaching for 34 years

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters