Is the end nigh for performance-related pay?

When issues over teacher pay were resolved earlier this year, the obvious focus was on the agreed pay increase of 6.5 per cent.

However, that wasn’t the only recommendation the School Teachers’ Review Body report had made. Among its many other suggestions was one it had made a number of times before: to scrap performance-related pay (PRP) bonuses.

It said: “The existing obligation on schools to operate performance-related pay progression should be withdrawn.”

As its reasons, it cited everything from the burden of administering it compared with the benefits it offers in terms of staff retention, to concerns around it not being “fully equitable for some groups with protected characteristics or for part-time workers”.

The STRB’s 2022 report also voiced such concerns, as did the 2021 report, which contained numerous objections from education unions, such as the Associational of School and College Leaders (ASCL), who said the approach had a “negative impact on retention and workload”; the NAHT, who called it “divisive and flawed”; and the NASUWT, who said it was a “widespread failure”.

Yet, despite all these criticisms, PRP remains very much in place.

PRP vs pay increases

Given that removing it would effectively reduce teachers’ chances of earning more money at a time of heightening concerns around pay, it’s perhaps understandable that the government has felt removing another potential financial boost to teachers does not make sense.

However, in Wales, PRP was dropped in 2020 owing to many of the same concerns outlined above. Instead, teachers now receive a pay increase every year, irrespective of performance - unless a teacher has been placed on capability procedures.

Eithne Hughes, director of ASCL Cymru, said the change has been a positive one: “The reintroduction of pay scales and the removal of PRP have helped create a fairer and more appropriate pay structure.”

MAT freedom

What’s more, in England, several large multi-academy trusts have used their freedom to operate more independently to move away from PRP, such as E-ACT in 2019 and Northern Education Trust (NET) in 2020, with the latter’s CEO Rob Tarn saying at the time that he felt there was little to be gained from its use.

“The formal process of lesson observation, numeric targets and the link to pay progression causes staff undue workload and anxiety, but there is little impact in terms of student performance,” he said.

Reflecting on this decision now, three years on, Tarn says it was “one of the best things we ever did” and that, as part of a series of other reforms, it has coincided with “student outcomes improving dramatically and all our schools are now rated ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ [by Ofsted]”.

He is keen to note, though, that removing PRP did not happen in isolation: “You can’t simply remove PRP without changing anything else.

“You need to create a culture of high expectation that drives improvements, and that may mean other reforms in a school or trust, but certainly we’ve seen no negative impact from removing it.”

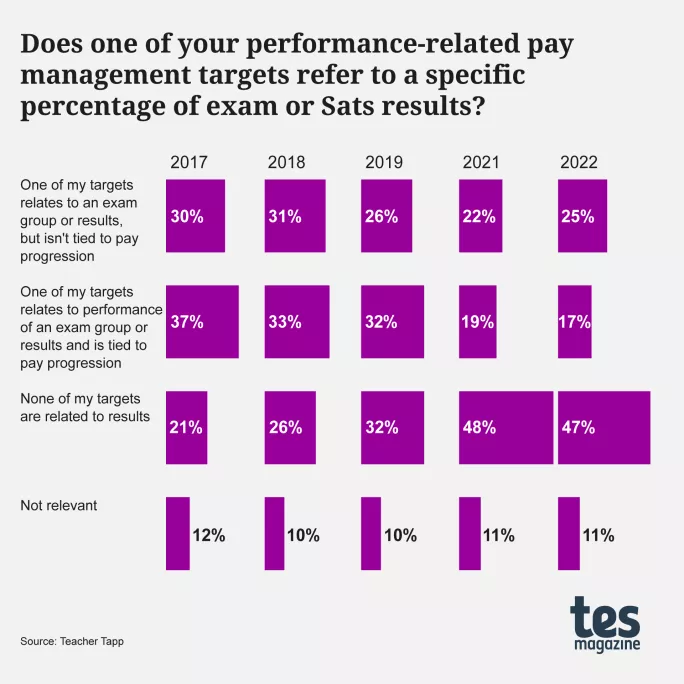

Clearly, others are willing to go through this, though, with Teacher Tapp surveys over the past five years showing a clear drop in popularity: only 17 per cent of respondents said a form of PRP was used last year, compared with 37 per cent in 2017.

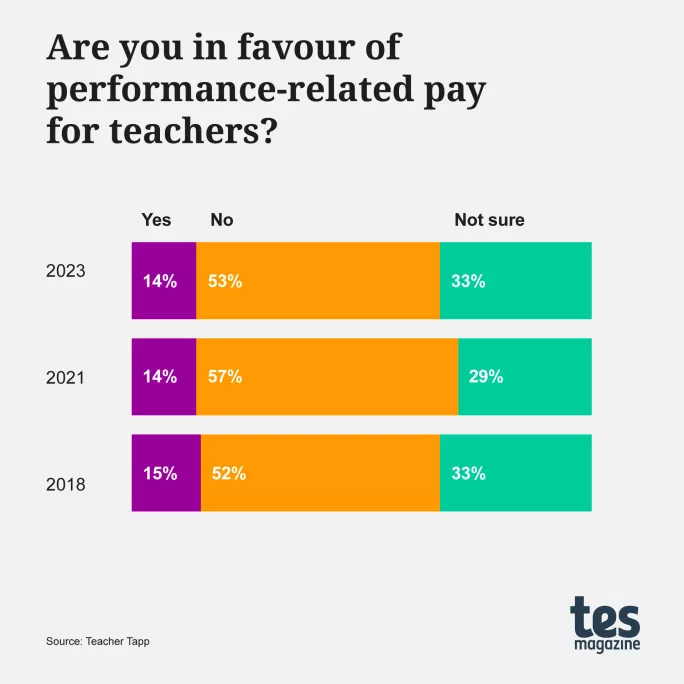

This does not mean, though, that none are in support of PRP, with other Teacher Tapp data showing a small but consistent group in favour of its use.

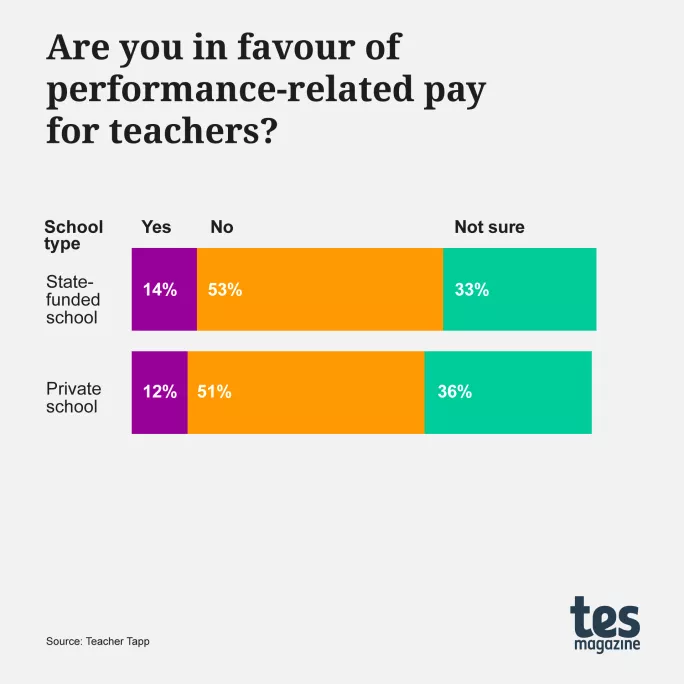

Breaking down the data from “Yes” voters, it’s clear that those in favour come from across the sector, with a similar split between state-funded and private schools.

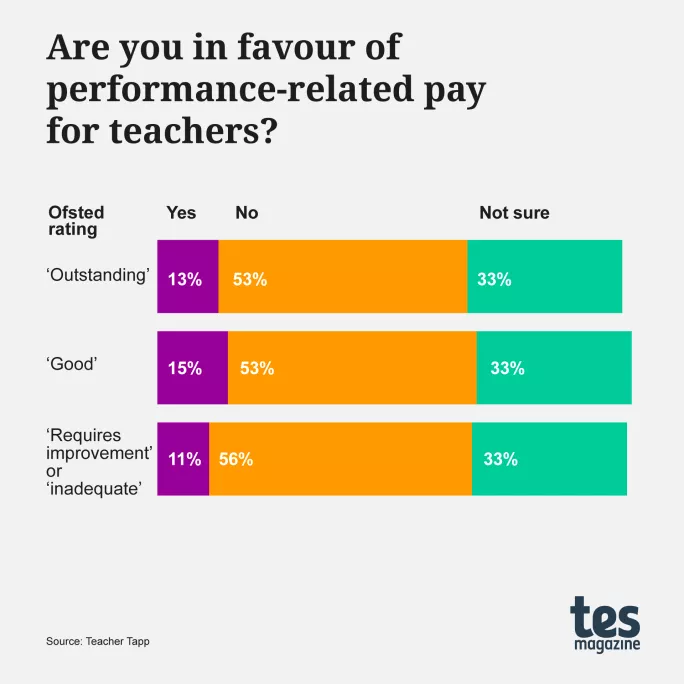

Similarly, the Ofsted grading of the school appears to bear very little influence over the teachers’ feelings of support towards PRP.

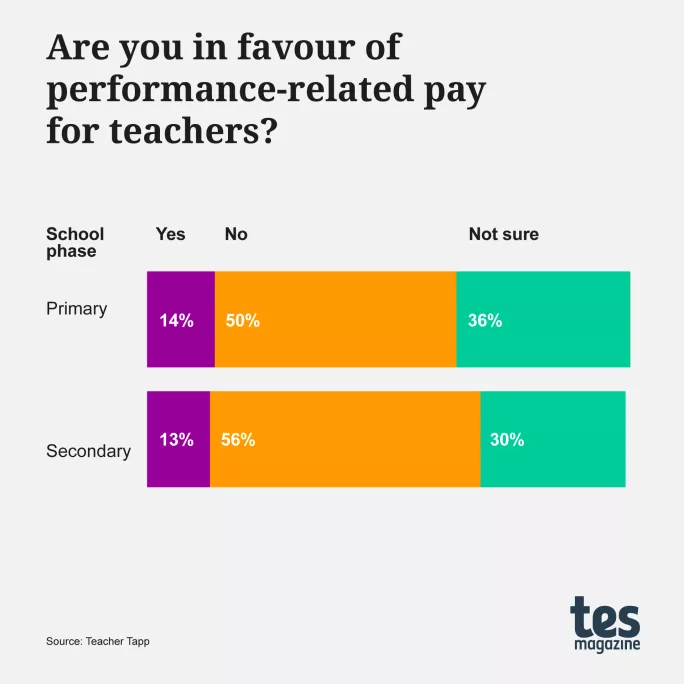

How about the high-stakes nature of the test results PRP could be based on? Well, whether the teacher works in a primary or secondary setting, feelings towards PRP seem to stay the same.

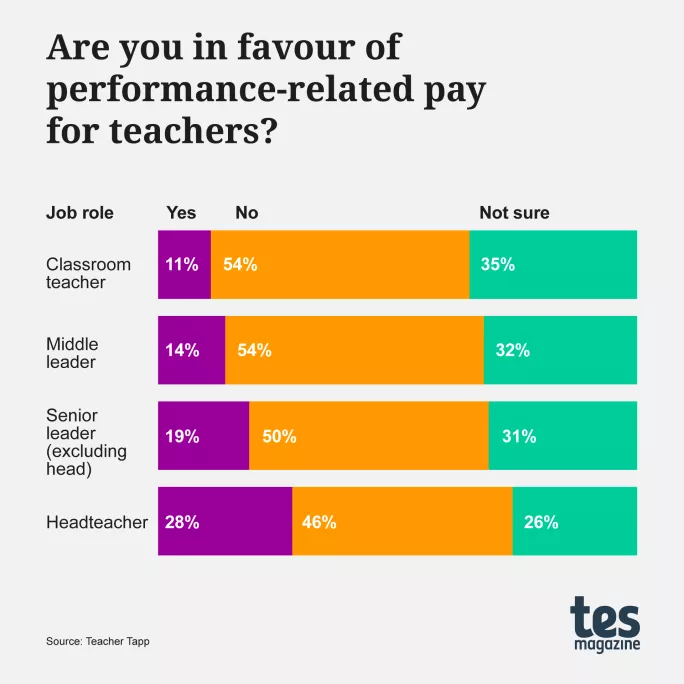

What did seem to make a difference, however, was the level of responsibility an individual held. As you climb the ladder of promotion, you become more likely to vote in favour of PRP.

It seems, then, if the government were to move to scrap PRP, it would be senior leaders most put out - not least because it gives them the ability to ensure underperforming teachers cannot “coast” up the pay scale, as one anonymous headteacher in the Midlands tells Tes.

“The problem is, in the private sector, ineffectiveness isn’t tolerated in the same way,” they say.

“It’s unfortunate that PRP is used incorrectly by some leaders. However, I think it’s right we keep it to motivate teachers and reward those who are highly effective.”

They add that they would worry “automatic progression can lead to complacency” and that “headteachers need to have a way to reward those whose performance merits an increase, especially when retention is so difficult”.

‘Heads need a way to reward those whose performance merits an increase, especially when retention is so difficult’

Shabnam Ahmed, head of department at a school in Suffolk, says she too prefers the idea of receiving financial rewards for performance as it not only brings “focus” to her role but shows teaching quality has value.

“I prefer PRP to automatic progression because I feel it ensures that all members of staff are held accountable and good performance is rewarded,” she explains. “It’s time people saw teaching as a profession that requires skill and expertise.”

Leah Crimes, a headteacher in Wales, where PRP no longer exists, says she can understand these arguments.

“While I inherently believe [experience-based pay progression] is right, I do believe that in certain cases the option of rewarding outstanding contributions to the school could be a motivating and affirming ‘bonus’ for teachers,” she says.

‘Highly problematic’

However, Crimes says the removal of PRP has been for the better as it carried the risk of being “used vindictively or inappropriately” and creating a “toxic and anxiety-inducing atmosphere in schools”, whereas the new model avoids this.

“From the point of view of classroom teachers, what we have in Wales now is an improvement on what existed before - it’s a far less stressful system,” says Crimes.

Tarn, too, says he has seen these benefits since ditching PRP: “It helped drastically reduce workload and administration for leaders and stress for staff who previously faced numerical targets linked to pupil outcomes, even though lots of things that contribute to outcomes are out of their hands.”

For those still stuck with PRP, these are exactly the issues they face and want to be rid of, with Jennifer Webb, a senior leader in the North of England, calling PRP “highly problematic” - not least because there is no uniformity in how it should be implemented by schools.

“Implementation of PRP varies between every school and academy across the country and there is a massive disparity with the yardsticks used,” she says.

“There is no consistency and, as a result, the experience for teachers is inequitable.”

‘Woolly metrics’

In part, Webb says, this is because there is often a “lack of training for middle leaders on how to deliver PRP” and “the issue of maintaining objectivity when judging the performance of someone within your own department”.

Furthermore, she says that even if training is given, the lack of clear metrics for PRP makes it really hard to use fairly because of how easily “woolly metrics” can be used to determine payments.

She says: “PRP is meant to be incentivising good performance but because there is no consensus on what ‘good performance’ is, PRP becomes something too easily manipulated.

“At the moment, there is no consensus on what can be used to measure performance because in both primary and secondary not everyone teaches the exam classes, and even then not everyone agrees on how to measure that success.”

‘There is no consistency…the experience for teachers is inequitable’

Given all these concerns, it is perhaps not surprising that unions like ASCL have repeatedly called for it to be abolished, with director of policy Julie McCulloch saying they believe PRP is harming teaching.

“PRP is not beneficial to the education sector; it can have a damaging impact on staff workload and retention,” she says.

“It is time for pay to be completely decoupled from performance and for PRP to be removed from the School Teachers’ Pay and Conditions Document.”

McCulloch says that this would also help tackle the workload issues many leaders face: “It is very difficult to accurately and effectively measure performance and the most recent STRB report recognised that the burden of administering PRP exceeds any benefit that it is achieving.”

Underpinning all these concerns is the assessment of PRP in the Education Endowment Foundation’s Teaching and Learning Toolkit, which is based on a review of existing research. It has little positive to say about it: “The impact of PRP is low. Schools might consider other, more cost-effective ways to improve teacher performance, such as high-quality CPD.”

It also noted that if a school has a particular way of awarding PRP - such as linked to Progress 8 or attainment outcomes - this can “narrow the focus of teachers to particular groups or particular measures”.

An unfair system

One Sendco, speaking to Tes anonymously, says she has seen this first hand. She says teachers are often drawn towards wanting to teach pupils “based on how likely it is they will help them hit their target”.

They give the example of a set of lower prior-attaining pupils who had arrived at secondary with “overinflated key stage 2 grades” and who were clearly not going to achieve the targets set.

“Nobody wanted to teach them because of their impossible target grades,” she explained. “It was the same in every subject - and as a consequence, they were often given to temporary staff members, which obviously made their GCSE years even more disruptive.”

Furthermore, for staff working with children with special education needs or disabilities (SEND), PRP is also seen as hard to apply with any fairness or uniformity, as David Williams, director of inclusion at Park Academies Trust, outlines.

“PRP doesn’t really work for any child outside the normal range [of attainment],” he says. “If you use P8 or attainment [to determine PRP], neither of these measures will work when you’re in specialist provision or SEND because it’s much harder to ‘leap forward’.”

Williams gives the example of a teacher who helped a child eat with a knife and fork: “This changed his life, but we have no data to measure it. When you’re measuring people, there is no measure to cover the whole range.”

The future of PRP

Clearly, then, it seems there are many who would not lament PRP’s demise - and there are signs the government is starting to listen.

While nothing has happened yet, the STRB report notes that, regarding its calls for a “reassessment” of pay progression and the removal of schools’ obligation to use PRP, the government was receptive.

“We note that the government offered to take this approach as part of a settlement to the current pay dispute. We see this as a pragmatic approach pending further review,” it said.

Tes approached the DfE for comment on this but it declined to answer.

It seems likely, though, from the above line in the STRB report, that policy efforts considering the future of PRP in England are under way and that it could one day become a thing of the past, as has happened in Wales.

If so, it seems debates about teacher pay won’t remain out of the headlines for long.

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

topics in this article