Absence is a UK-wide problem. Here’s how to tackle it

Edinburgh secondary head Shelley McLaren recalls one student who, staff realised, was consistently absent from school on Tuesday and Thursday afternoons.

When teachers at Craigroyston Community High investigated why, it turned out that on these days the girl, Sophie*, had lessons in which she was sitting at the back of the class. Worsening eyesight meant she couldn’t see what was going on and - lacking the confidence to raise the issue with her teachers - her solution was to just stop attending.

A trip to the opticians and one pair of glasses later, Sophie was back in class.

That intervention was down to one of the school’s 10 “attendance champions”. These are existing members of school staff who are paid an extra £1,200 a year - the equivalent of an hour a week of overtime - to work with four students or four families for whom attendance is an issue.

Worsening school attendance is a problem across the UK but it can be hard for schools to tackle because there are so many different factors that may be behind regular absence.

New guidance on improving school attendance in Wales says that “we often talk in generalised terms about absence” but “the specific combination of causes for each individual often proves to be unique”.

The targeted approach of Craigroyston recognises how varied the reasons for missing school can be.

Its attendance champions’ focus is on students in the first year of secondary whose attendance is sitting around 80-85 per cent.

McLaren says attendance champions build relationships with families and get to the bottom of poor attendance.

They then maintain that contact, phoning and texting parents and carers to make sure all is well and that students will be attending school.

In Northern Ireland, it was reported in October that school attendance in 2021-22 had been the worst on record, with about 30 per cent of pupils having absence rates classed as “chronic” or “severe chronic”.

England also has higher rates of what it calls persistent absence than before the pandemic, and in September the Welsh government said it was setting up an attendance task force after it was revealed that 16 per cent of secondary students were absent for more than 20 per cent of sessions.

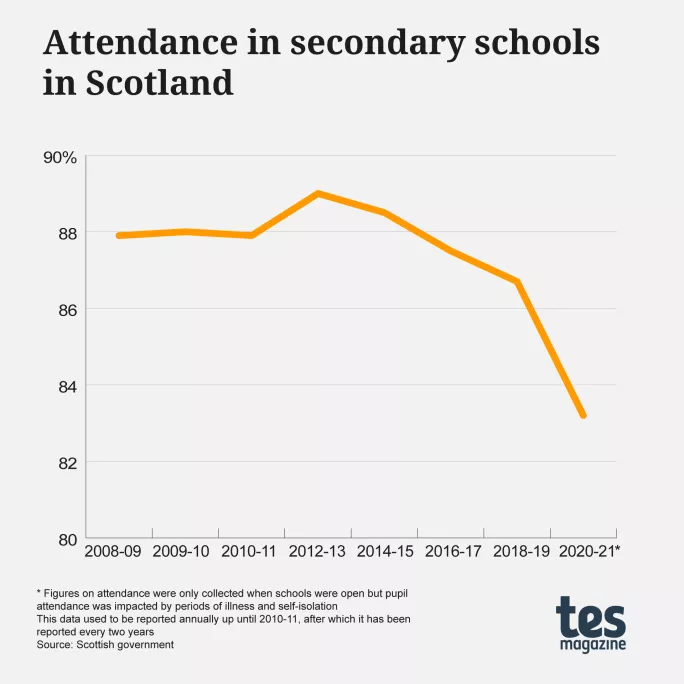

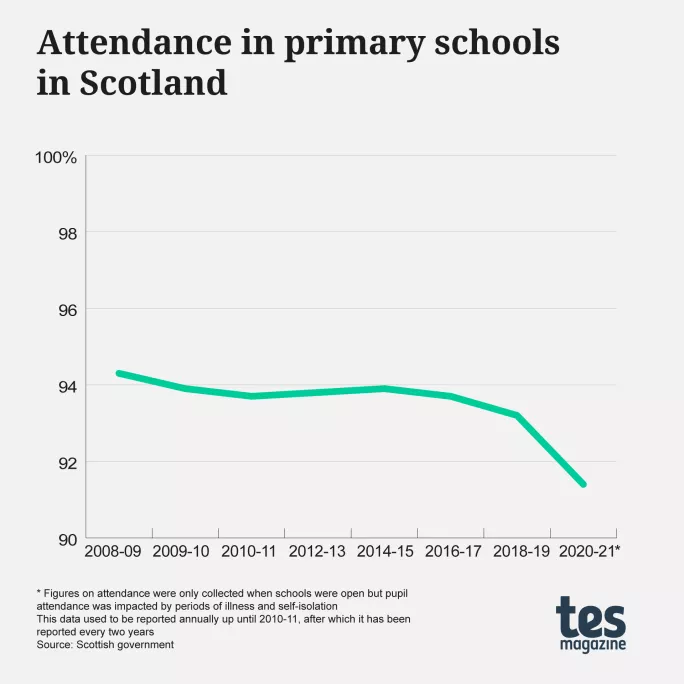

In Scotland, quantifying the problem is less straightforward. Figures on persistent absence are not published and the most up-to-date full-year official attendance data is for 2020-21 (more on that later), while the focus on overall attendance rates lacks nuance.

Worrying trends

However, the Reform Scotland think tank last week revealed concerning patterns that lie below these headline statistics, and headteachers and education directors consistently report that attendance has yet to recover to pre-pandemic levels.

And recently, an assistant director of education said that secondary students were “regularly taking a four-day week”.

Education secretary Jenny Gilruth has admitted that there is a problem at certain ages and stages, such as students now in S4, who were in P7 in March 2020 and had transition plans heavily disrupted.

In terms of what is causing the decline in attendance, poor mental health among both pupils and parents is often cited.

It is also often suggested that during the Covid pandemic - because of partial school closures, self-isolation and illness - many young people simply got out of the habit of going to school.

- Improving attendance: a research view of what works

- Causes of absence: Schools need help to tackle this crisis

- Attendance: what’s gone wrong?

McLaren says losing that routine is definitely part of the problem - but so is the grinding poverty that many families are facing. The cost-of-living crisis saps the energy of parents who work three jobs to make ends meet and still rely on food banks and the food parcels that McLaren and her staff started delivering during Covid and continue to deliver now.

“The poverty in our community at the moment has gone back a decade,” she says. “It is horrendous and because of that there is this apathy - and that extends to school.

“People find it hard to see the point of anything - they cannot see how life is going to get better. So it is a huge challenge just to get the pupils in the door.”

And although attendance champions are making a difference to individual young people who otherwise would be absent more of the time, McLaren admits that the overall pattern of deteriorating attendance is proving hard to turn around.

No quick fix

Attendance champions focus on students with poor but not awful attendance. Students seen in school even less frequently will need a “multi-agency” approach, she says; in many cases, there is no quick fix.

This is echoed by Lorraine Sanda, Clackmannanshire education director and the chair of the Forth Valley and West Lothian Regional Improvement Collaborative (RIC).

The RIC made attendance a focus after a 3 per cent drop, compared with pre-pandemic data, across the four local authorities it comprises: Clackmannanshire, Falkirk, Stirling and West Lothian. Sanda says there is “no silver bullet” and does not expect to see big improvements within a short period.

“The problems are challenging, so you don’t get massive shifts unless you have been doing something wrong in the first place, like not recording the data properly,” she adds.

Like McLaren, Sanda believes pupils are attending less because attitudes to school have changed: coming to school is no longer a “have to do”, just a “good to do” in certain circumstances. She adds that mental health issues among pupils and parents are “having a significant impact”.

Yet, she believes, the action required to buck the trend is “not rocket science”: schools that want to improve their attendance just need to have a “relentless focus” on it.

Schools have so many competing priorities that doing this is actually quite tough, admits Sanda, so the RIC is there to “give them a bit of a hand”.

In practice, that has meant helping schools to crunch the numbers and define the problem, thereby making it easy for staff to understand what the research says works - and supporting schools to do more of it.

The Forth Valley and West Lothian RIC’s “self-evaluation toolkit” was devised to help schools evaluate and improve on strengths around attendance. It asks them to think about whether learners feel safe, cared for and nurtured; if attendance and punctuality are promoted by the school; and if there are clear processes for flagging and tackling persistent absence.

There was also an advertising campaign to coincide with the return to school in August, with buses and a local radio station promoting the message “Be inspired. Be involved. Be in school”.

Curriculum and school ethos

Sanda - who used to be the Scottish government’s parental involvement coordinator - is clear that improving attendance isn’t just about hectoring and cajoling parents and pupils back into good habits; it’s also about giving pupils something to come to school for. What happens in the classroom? What courses are on offer? What is the atmosphere like in school? Do pupils want to be there? And if not, why not?

“This is the biggest message of all - and I think it’s the hardest one,” she says. “Children should want to come to school and they will only come to school if you get the curriculum right and the ethos right.

“So it’s not a punitive approach. It’s: ‘You’re responsible in your school for making sure that those kids want to turn up, and turn up as much as they possibly can to learn.’”

The Welsh government is also talking about the importance of making school a place that pupils want to go to. Its new guidance, Belonging, engaging and participating, says “attendance will improve if learners actively want to come to school” and tells schools to make what they offer “engaging, interesting and relevant”.

In Scotland, there have been some interesting examples of schools doing just that.

Grove Academy in Dundee - as part of the Every Dundee Learner Matters project - introduced a tailor-made curriculum for a group of a dozen boys who were “boisterous, physically aggressive and immature in their attitudes” and “opposed to learning in the traditional fashion”.

Initially the focus was on football activities, then on giving them experience of working in different trades. Grove also used fashion and design to make school more enticing for a group of girls who were “disengaged”, “withdrawn” and “anxious”.

Low-cost solutions

That kind of bespoke approach comes with a price tag - but not all interventions to improve attendance are costly.

At Fallin Primary School in Stirling - which serves the former mining village of the same name - replacing the rather austere standardised letters they sent out to families to highlight falling attendance with more empathetic versions, emphasising the help and support available, sparked a flurry of engagement from parents.

Aisling Shandley has been leading Stirling’s school attendance work along with educational psychologist Heather McLean.

Shandley explains: “There are often very valid reasons why a young person is not able to engage with school at a particular point in time, so it’s about the sensitivity of the communication with home.

“A number of schools looked at changing the wording of the communications that went home.

“So instead of saying ‘missing a day means this happens’ or ‘missing a week means that happens’, it was about trying to reframe it so it was about ‘you belong here, you are part of this school and we miss you’.”

‘Children will only come to school if you get the curriculum right and the ethos right’

In March, Fallin Primary - which has a roll of around 200 pupils - sent out more than 80 of the new-style letters flagging poor attendance, and received responses from around three-quarters of parents and carers.

Through that engagement, the school found that many children were anxious about coming in, and parents were at a loss as to how to get them in.

Michelle McAvoy, the school’s health and wellbeing support officer, now goes out to support families in the morning and get children ready for school. She chats to the pupils, giving them their clothes to get ready and generally provides parents with that support, chivvying the children along.

“It’s just a matter of saying ‘right, come on, it’s 8.30’ or ‘it’s 8.45, you need to get up’. And then before you know it, you hear the feet moving about up the stairs and they are up getting ready,” she says.

Acting depute head Sarah Lamont says the school has also become aware of parents who physically struggle to get their children ready for school because of health issues, and of split families that mean children do not live locally on some days.

The school is also seeing a rise in “precautionary absences”, whereby families are more inclined to keep children at home with minor coughs and colds.

More recently, attendance has taken a hit because families are taking holidays in term time to save money.

Monitoring attendance

Now, McAvoy monitors attendance every day and has a group of target children who check in with her in the morning. They keep personal journals, tracking their attendance using stickers, and if they are in every day of the week, they get a certificate on the Friday; if they maintain their attendance for a few weeks, they get to take a prize home.

Good attendance is also celebrated at assembly, and the class with the best attendance each Friday gets a certificate.

McAvoy and Lamont stress the importance of building good relationships with families, and McAvoy says she has an “open-door policy” when it comes to parents and carers.

Another important aspect of the school’s work, says Lamont, has been helping families to understand the importance of attendance.

One piece of research summarised by the RIC for schools, and published last year by University of Strathclyde researchers, says that a 1 per cent increase in days absent was associated with a 3 per cent decline in educational attainment.

In other words, every day counts.

Changing patterns

But questions are being asked in Scotland about how well we can get to grips with the challenge that attendance is presenting at school level when the data at a national level is so poor, with the most recent annual figures dating back to the 2020-21 school year (see the graphs above).

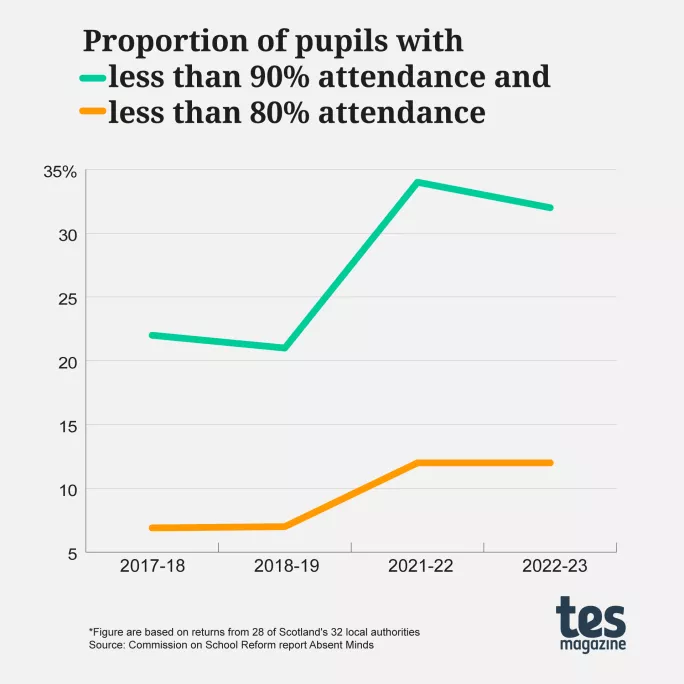

New official figures will be published in December but, being focused on overall attendance rates, they are unlikely to shed as much light on changing patterns as those revealed last week by the Commission on School Reform, part of the Reform Scotland think tank.

Using freedom of information legislation, the commission showed that 18 per cent of Scottish secondary students attended school less than 80 per cent of the time last year. Some 40 per cent attended less than 90 per cent of the time; in 2018-19, the last year before the pandemic hit, that figure was around 30 per cent.

Attendance in primary was better but had also fallen in recent years.

While 15 per cent of P1-4s had an attendance rate of less than 90 per cent (or at least one day off every fortnight) in 2018-19, by last year that had risen to a quarter (25 per cent).

The below graph shows figures for primary and secondary schools combined:

The commission described the figures as “alarming” and called on the government “to conduct a proper investigation into the problem” and to provide better, more detailed attendance data.

This is echoed by the University of Strathclyde researchers who quantified the link between attendance and attainment, Edward Sosu and Markus Klein.

They welcome the fortnightly data published by the government on its attendance dashboard but say it must be “accompanied by a more in-depth analysis and monitoring of trends over time” - for instance, are the reasons for absence stable or do they change?

They add that biennial summary reporting should be replaced with “at least annual reporting”.

So, just as good data is essential for the schools and councils determined to make inroads on attendance, the message is that the government needs to get to grips with the scale of the problem at a national level.

But there is another reason why national leadership is needed on this issue.

Schools can solve some of the problems that lead to poor attendance, such as figuring out that a pupil needs glasses or helping children to cope with low-level anxiety so they can get to school in the morning.

But another reason why pupils are not coming to school as much as they used to is poverty and its suffocating effect on hope and aspiration.

The government needs to acknowledge, therefore - as has happened in Wales - that “this is a crisis which needs a national approach” so that all pupils get back into the habit of coming to school.

*The pupil’s name has been changed to protect their identity

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article