Is the school buildings crisis solvable?

After news of the reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) crisis broke, leading to disrupted learning for thousands of pupils at the start of term, Department for Education permanent secretary Susan Acland-Hood told MPs: “We and the Treasury are clear that this is the first priority.”

There are now 214 schools confirmed to have buildings containing the collapse-risk RAAC, according to the latest update from the DfE, and that number is expected to grow: the DfE identified 14,900 schools with buildings from the period in which RAAC was used.

The DfE has promised to fund all the capital costs of putting mitigations in place for RAAC, as well as most revenue costs for schools affected.

However, nearly three months in, the department has yet to specify how much money is available or how it will be allocated.

And, as Tes reported last month, the so-called crumbly concrete is just the tip of the iceberg as a much larger proportion of schools face problems such as asbestos, cladding issues, boiler issues and leaky roofs.

As we approach the Autumn Statement from the chancellor - in which Jeremy Hunt will have the chance to demonstrate if there is money behind Ms Acland-Hood’s claim that the school building crisis is a priority for the government - Tes looks at how much is needed to begin to address the school buildings crisis.

- RAAC: ‘No end in sight’ to RAAC saga, warns union leader

- Walker: RAAC cash mustn’t come ‘at expense of SEND’

- School budgets ‘stagnate’ as increased costs use up funding

Before the scale of the work on RAAC came to light, the National Audit Office (NAO) had already warned that “following years of underinvestment, the estate’s overall condition is declining and around 700,000 pupils are learning in a school that the responsible body or DfE believes needs major rebuilding or refurbishment”.

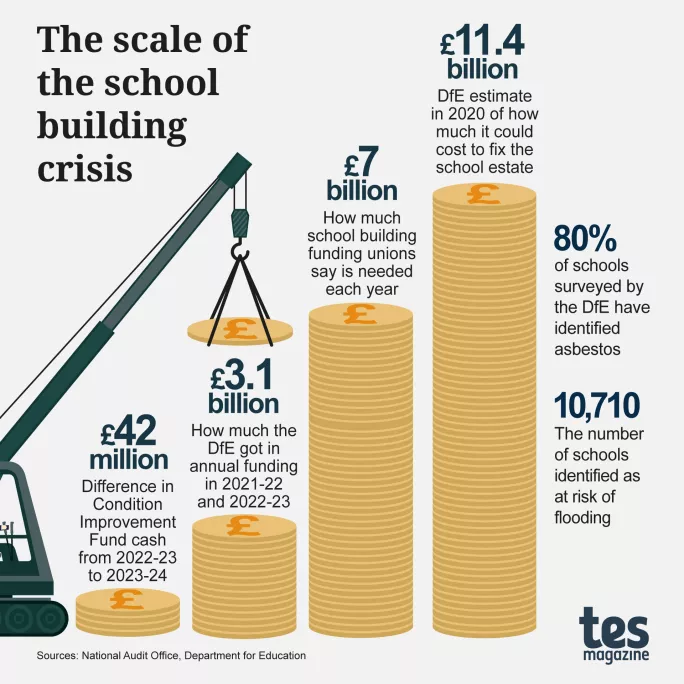

The DfE estimated in 2020 that it would cost £11.4 billion to return the entire school estate to good condition, based on data collected from 2017 to 2019 (it is worth noting here that RAAC only became known as a big issue in 2018 when a school ceiling collapsed).

The Office of Government Property estimated in 2019 that the DfE would most likely need £7.1 billion just to maintain the school estate.

More than £15bn needed to fix schools

“If you add in RAAC and inflation to that estimate, we are definitely looking at north of a £15 billion backlog to return the school estate to a good condition,” academy funding consultant Tim Warneford told Tes.

The DfE requested an average of £4 billion a year from 2021 to 2025 at the 2020 Spending Review, to increase in later years. The Treasury then allocated £1.8 billion for 2021-22 maintenance and repair, and around £1.3 billion a year for the 10-year school rebuilding programme (SRP) - this funding remained the same for 2022-23.

The SRP carries out big rebuilding and refurbishment projects for schools and sixth-form colleges across England.

However, experts have warned that the current rate of investment is not enough to keep pace with the rate of dilapidation.

Just in terms of RAAC-related costs, the DfE is set to be billed for extensive revenue and mitigation costs incurred by affected schools, such as for transport to alternative spaces and materials for propping up walls, in addition to the cost of putting temporary classrooms in place where needed.

Michael McCluskie, director of learning at Coast and Vale Learning Trust, said the DfE has been really supportive in helping the school get all their pupils back into face-to-face education over the two months since RAAC was confirmed at Scalby School in Scarborough.

He said the school had built up around £450,000 in costs so far, “which the DfE has promised to fund”.

“The DfE has also arranged for us to get 17 temporary classrooms for specialist subjects, which we should have in place by March next year. It’ll cost the DfE just under a million to lease those,” he added.

Damp and mouldy classrooms

While RAAC is undoubtedly the most high-profile issue for the school estate right now, many schools are facing a host of other issues that could put learning at risk.

More than 80 per cent of schools surveyed by the DfE in March this year had identified asbestos, and the Health and Safety Executive reported in the summer that 7 per cent of schools it surveyed had significant failings in their systems to manage and monitor the issue.

Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), told Tes: “We simply cannot continue indefinitely having to manage [asbestos] when it is perfectly obvious that the only real solution is to remove the stuff altogether through a phased programme.”

Mr Warneford also said there are concerns that asbestos will have to be dealt with first to allow schools to properly survey or deal with RAAC.

The government SRP prioritises school buildings in the very worst condition, particularly if their condition needs are urgent. Some schools that may now be able to receive government funding to cope with the RAAC crisis had previously tried and failed to get selected for the SRP.

“We had previously applied for the SRP and been rejected,” Mr McCluskie said. “A lot of our buildings are very old and the school is at capacity - we’ve got two blocks that are completely not fit for purpose for the class sizes we now need and, condition-wise, are very uncomfortable for pupils and staff in summer and winter.

“In a way, RAAC has done us a favour because there have now been more conversations about Scalby and the SRP that I feel optimistic about. It needs rebuilding work,” he added.

Meanwhile, nearly half of all schools in England (10,710) were said to be at risk of flooding by the DfE last year.

The RAAC crisis may have disappeared from the daily headlines, but the issue is far from over.

More than one in five of the 214 schools (46) had enough RAAC that they had to delay the start of term or move some pupils online at least temporarily.

And last month, Wakefield’s St Thomas a Becket Catholic Secondary School announced it would have to use remote learning for many pupils due to the discovery of RAAC, after the most recent update to the list of schools with the problem.

Education secretary Gillian Keegan said at the beginning of September that any schools with suspected RAAC would be surveyed within the following two weeks. But DfE minister Baroness Barran told the House of Lords last week she was unable to provide an exact timeline for actually clearing RAAC.

Issues with existing funding

Schools with major issues with their estates, aside from RAAC and which are not enough to get SRP funding, are reliant on being selected for other DfE pots of funding - such as the Condition Improvement Fund (CIF), School Condition Allowance or Devolved Formula Capital.

CIF is an annual round of capital funding that some academies, sixth-form colleges and voluntary aided schools apply for. It is open to smaller trusts only, meaning around 5,000 schools are eligible.

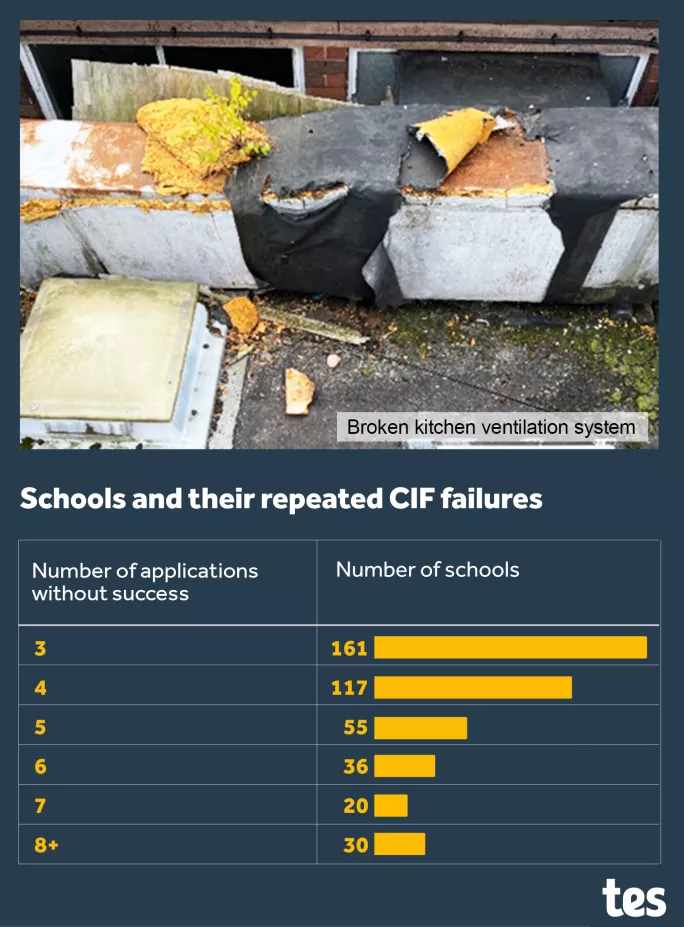

Tes revealed last year that more than 400 schools had had their CIF bids rejected at least three times since 2016 without a single success.

This year, 1,033 projects were approved for CIF funding across 859 schools. That was nearly 20 per cent less than in 2022-23 when 1,408 separate works were successful, and similarly below the previous two years when more than 1,400 projects were approved.

This meant that the total funding for 2023-24 amounted to £42 million less (£456 million compared to £498 million the year before - an 8 per cent decrease) than the funding the year before.

Mr Warneford said this was because the “size of the pot” was not increased in line with inflation.

“We’re desperate to hear that they’re going to make the pot keep pace with inflation for the next round of bids submitted,” he said.

“If it stays static, I’d estimate we’ll probably see less than 1,000 projects approved.”

Decarbonising and sustainability

The DfE promised in 2022 all new school buildings that hadn’t already been contracted would be net zero in operation - though the NAO cautioned this only covered 2 per cent of schools.

The DfE has also said the flood risk will have been reduced in over 800 schools by 2026.

Around 60 per cent of energy use in education settings was associated with fuels such as gas, coal and oil as of last year, which the DfE is also addressing by helping them replace things like boilers with heat pumps.

Seven of 143 of the DfE’s sustainability commitments are off-track, Baroness Barran told the Environmental Audit Committee.

Net zero

Mr Warneford said the Net Zero Accelerator pilot, which is testing how much it could cost to retrofit schools, has estimated it will cost around £15 billion to bring the school estate in line with net zero requirements.

“We can’t fully decarbonise our estate until we fix our estate,” said Mr Warneford. “You can’t put things like new heat pumps in falling apart buildings but also you can’t fix the buildings properly without addressing the sustainability issues.”

The DfE received £342 million from the Public Sector Decarbonisation Scheme’s (PSDS) phase three to help with its work, Dr Jonathan Dewsbury, the DfE’s director of capital operations and net zero, told MPs on the Environmental Audit Committee last month.

The PSDS gives grants to public sector bodies for decarbonisation and energy efficiency work.

Juggling priorities

When asked by Dame Meg Hillier MP at the Public Accounts Committee in September what things would not be prioritised by the DfE when bidding for funding at the next Spending Review if RAAC was the “main draw on capital funding”, Ms Acland-Hood said: “It does not stop us bidding for other things.”

However, Baroness Barran was unable to provide assurance the DfE would be able to meet its sustainability targets given the focus on RAAC when quizzed by Claudia Webbe MP at an Environmental Audit Committee session.

The DfE bids for separate funding for rebuilding and for maintenance and repair, as set out in the NAO report.

Commons Education Select Committee chair Robin Walker has also urged the government to make sure prioritising RAAC at the Spending Review doesn’t come at the expense of important funding for special educational needs and disabilities.

All of these competing priorities come in a difficult economic environment, with “enormous burdens” on public services following the pandemic, according to a report.

The recent report from the Centre for Progressive Policy projected that public spending in the UK will need to rise by nearly £142 billion a year by 2030 for public services simply to be maintained as they are.

Within that, researchers estimated education spending would need to increase by nearly £9.8 billion a year by the end of the decade.

This projected figure does not include the investment needed to restore school buildings, researchers added.

Can we fix it?

Education unions have already called for an extra £4.4 billion to be spent annually on school buildings, so the total yearly spend would be £7 billion. ASCL has since repeated this call in its Autumn Statement representation.

In a letter to the DfE, unions highlighted how civil service officials previously called for the SRP to be increased from 50 projects a year to more than 300.

A total of 400 of the 500 slots in the SRP over the 10 years have been filled so far, with many in the sector expecting the last 100 to be used for some of the schools with RAAC.

Ms Acland-Hood told MPs last month that the DfE would look at increasing the size of the SRP if needed.

But Mr Barton told Tes: “By any estimate, there is a huge job to do in upgrading and making safe the school estate.

“The fact that the government has cut capital spending by nearly 50 per cent in real terms since 2010 has made the backlog of refurbishment and repairs much greater than it should be.”

“This won’t be solved all at once, but what is needed from the government is a commitment to ensure that annual spending is set at a level that progressively addresses all the requirements over time and ensures we don’t fall even further behind,” Mr Barton added.

Mr Warneford warned that existing “issues that risk life and school closure” will only get worse ”if the can is kicked down the road”.

He added: “To make a difference, it will require a hugely significant investment - an almost historical change of focus. At some stage, someone has to do it; the funding for buildings at the moment isn’t touching the sides.”

The DfE did not give an answer when Tes asked how much it would be bidding for in the Autumn Statement. The government has previously said it will spend what it takes to keep children safe, and the DfE’s funding position doesn’t prevent it from addressing any immediate issues.

The NAO’s report says that the DfE “has received significantly less funding for school buildings than it estimated it needed” since 2016.

It seems clear that the Treasury will need to be significantly more generous to the DfE in the Autumn Statement than in the past to meet the levels of funding needed to fix the crumbling school estate.

However, union leaders are not optimistic. Niamh Sweeney, deputy general secretary of the NEU teaching union, said: “Given the cuts in capital funding over the last decade, it is abundantly clear that the current government is not committed to making all our school buildings, safe, comfortable and sustainable.”

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters