Why a 32.5-hour week will just lead to longer lunchtimes

Behold! After six years, the government has revealed its massive new plan for improving schools, which is…that they should open for 32.5 hours per week. Eh? Don’t they do that anyway?

In truth, no. Some schools open as early as 8.30am, and some finish as late as 4pm. And not everyone stretches across 6.5 hours each day (which is what you need to hit the 32.5 hours).

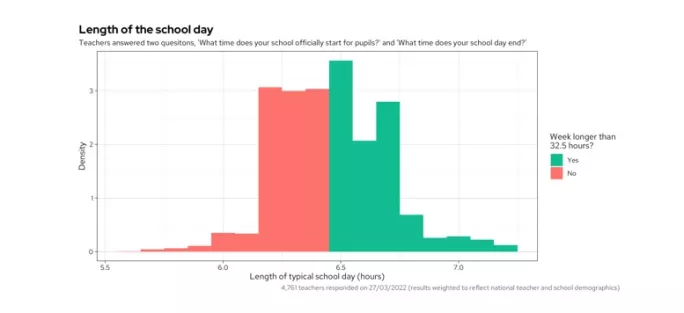

Roughly 60 per cent of schools hit the metric, whereas the other 40 per cent do have a slightly shorter week by only a few minutes - as the below graph from Teacher Tapp data shows.

If you’re sitting in a government office and you see this written down, it’s understandable that you might be alarmed. “How dare teachers steal five minutes a day from children’s education? Over a childhood, that’s loads of time. We must correct it immediately!”

The only problem is that when you look closely at what is going on in schools, it doesn’t appear to be teaching time that is cut back.

Instead, it’s a reduction in lunch and breaktimes.

Do we need a rule on the length of the school week?

To delve deeper, the app that I co-founded, Teacher Tapp, polled a representative national survey of around 7,000 primary and secondary teachers across England.

We asked about the start and end times of their school day, plus lunches, breaks and early closures.

As expected, lunchtimes vary. But, overall, it’s clear that the longer your school lunch runs, the longer your school day seems to be.

For example, schools that have children on site for the full 32.5-hour week also have an average lunchtime length of 50 minutes. Schools in for less than a 32.5-hour week? Their average lunchtime length is only 40 minutes.

So yes, those 10 minutes a day do add up - but for many schools, it’s coming from sarnie-munching, not science lessons.

So, why might a school choose to run a short lunch? First, it’s cheaper - less lunchtime means less supervision time.

Then there’s the issue of split lunches. Getting primary pupils through universal infant meals or reducing queue-fighting in secondaries can be a challenge.

So some schools make pupils take their lunches in shifts. If the lunches are too long, it can be hard to manage the timetable. No one wants to be the student on the 1.30pm lunch slot, nor does it seem right to start eating before noon!

Again, does the data bear that out?

Yes, at least in secondaries. Schools that run split lunches have an average of 37 minutes for lunch. Those that do not have 43 minutes. Only a five-minute difference but, as we’ve seen, that’s often the only difference between the groups that hit the 32.5-hour week and those that don’t.

Secondary schools also reported shorter breaks (usually around 15 minutes rather than 20), which correlate with more secondary schools having shorter days and earlier closures one day per week- again suggesting that it’s not that teaching is being cut back, so much as social time.

So is it a pointless policy?

Not entirely. We did find some primary schools that have a long-ish lunch and don’t hit the 32.5-hour week.

It’s likely to be a small percentage and there may be reasons that we don’t know about (especially around transport), but we can’t say categorically that no schools have shorter weeks due to less teaching.

But the data would suggest it’s very unusual.

For most of the others, the new standard can likely be met by adding time back on to lunch and breaks, which won’t necessarily be cheap.

One school leader on social media said they estimated that it would cost over £90,000 in additional labour to do so. But it does give parents some stability and guarantees around what they can expect from schools.

At present, early finishes might reduce the financial burden for schools by cutting out 10 minutes of supervision time, but that cost transfers to working parents, who then have to pay for after-school childcare.

The policy also stops schools from taking tactical moves, such as those seen before the general election of 2019, when they either threatened to or started to close early in response to funding cuts.

But what about academies?

What isn’t clear, however, is how the policy interacts with academy “freedoms”. Schools that are academies have the right to set their own school day and their own term times. They are allowed to have additional Inset days, and many do.

An additional three Inset days per year is equivalent to knocking six minutes off school each day - yet that isn’t likely to break the rules, whereas knocking five minutes off break time will. If I had a shrug emoji, this is where I’d place it!

In the end, it looks as if this policy is going to cause a lot of timetable shifting, mainly for the gain of a bit more break or lunchtime. But perhaps what it really signals is the end of academy ‘freedoms” as we knew them.

Laura McInerney is co-founder of data organisation Teacher Tapp

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article