Are primary teachers the answer to the secondary recruitment crisis?

This article was originally published on 18 July 2023

The pupil population is declining - and fast.

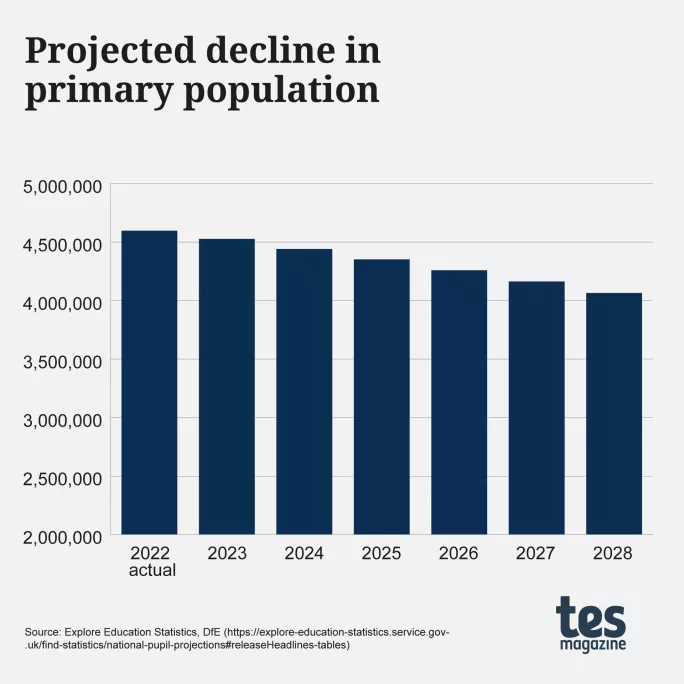

The Department for Education’s own pupil projection data shows that, by 2028, there will be half a million fewer children in nursery and primary schools compared with 2022.

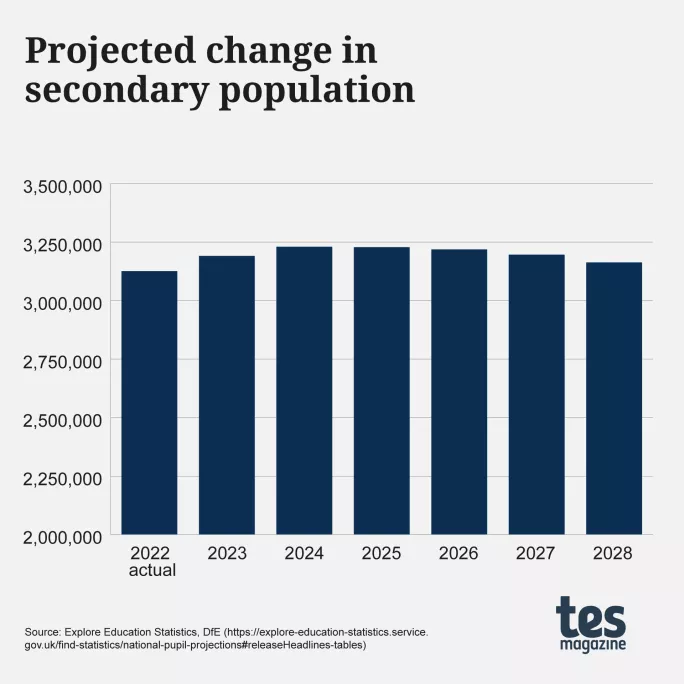

However, secondary school populations will grow slightly, as a population “bulge” works its way through the system.

It is perhaps no surprise that recent government targets for recruiting new teachers reflect these trends, with secondary teacher recruitment targets increasing 25.9 per cent from 20,945 to 26,360, and primary falling 21.2 per cent from 11,655 to 9,180.

This change follows significant over-recruitment in primary compared with secondary over the past few years, too.

In short, the primary sector is set to be underpopulated by pupils and overstaffed with teachers at exactly the same moment the secondary sector is struggling to recruit with no respite on pupil numbers.

Improved transition

Could there be a logic in encouraging more primary teachers to move into secondary to help reduce this pressure?

A leading expert on teacher workforce, Jack Worth from the National Foundation for Educational Research, says something like this could certainly be required as secondary recruitment remains so stagnant.

“Secondary recruitment is below target and doesn’t look like it will change,” he says. “Filling those shortages needs to come from somewhere, and primary teachers could provide a source.”

Qualification-wise, there are no issues, as James Zuccollo, director for school workforce at the Education Policy Institute, notes: “Currently, any teacher with qualified teacher status can teach in a primary or secondary school. Indeed, many move between the two phases.”

What’s more, Robert Young, general secretary of the National Association for Primary Education, says secondary schools could really benefit from bringing in primary teachers and their expertise, especially around improving transition.

“Transition for pupils from primary to secondary has been an issue partly because of the lack of collaboration between the two sectors,” Young explains. “[Bringing] primary specialists into the early years of secondary schooling in particular can only enhance continuity of experience between the two phases”.

This approach is exactly what the CEO of the Mossbourne Federation, Peter Hughes, has adopted to great success at his multi-academy trust.

“We’ve found that the expertise primary teachers bring is well suited to our nurture-set students,” he explains. “These students are still acquiring a lot of the essential skills such as reading fluency, which primary teachers are expert at teaching.”

Hughes explains they recruited and appointed a primary specialist to deliver the curriculum to the nurture group in a primary single-class-for-all-subjects model, arguing that this slowed the step up to secondary and reduced the need for multiple teachers and a complicated timetable.

“It was a great success - for the pupils and for the teacher,” he says. “It was exactly what they needed: an experience that felt familiar to what they had at primary school while easing them into secondary school life.”

KS3: no longer ‘the wasted years’

Lisa-Maria Müller, head of research at the Chartered College of Teaching, agrees there are a “number of potential educational benefits” to using primary teachers in secondary, including making stronger use of key stage 3.

“A shared understanding of primary and secondary curriculum [could] potentially reduce the risk of key stage 3 being ‘the wasted years’,” she says, arguing there would be greater continuity with regard to how learning is delivered between the two phases.

“[Primary teachers can] raise awareness about learning strategies or teaching approaches that students are likely used to,” she adds.

It’s something John Thompson (not his real name), headteacher of a secondary in the East of England, is hoping to capitalise on by employing a primary teacher to deliver KS3 maths - a move necessitated by a lack of secondary teachers applying for the role.

“We had been struggling to recruit in our maths department, and so together with my head of maths, we changed our recruitment strategy to target primary teachers with a specialism in maths and offered the role with a teaching and learning responsibility attached,” he explains.

To accommodate the primary specialist in the secondary setting, Thompson provided the teacher with a timetable made up predominantly of KS3 classes, freeing up the existing staff to take on more GCSE and A-level classes.

“We made the role more attractive with the TLR and used it to cover the responsibility of designing assessments in KS3,” explains Thompson.

“Next year, at his request, our new maths teacher will again have a KS3 majority timetable, but the plan is to add KS4 the following year.”

Although the school has had to accommodate a teacher who could offer less flexibility in the short term, Thompson says that, in the long term, it is the right choice for the school.

“We were really struggling to recruit, and realistically my option was to continue to use cover or take a gamble and invest in someone I felt would be the right fit for the school,” he says.

The challenge of subject knowledge

In this case, the concern for subject knowledge could be addressed by a slower phase-in for the GCSE curriculum - but Zuccollo points out that in smaller departments for other subjects, this might not be possible and leaders might find this a stumbling block.

“Some leaders might be asking themselves if primary teachers have the subject expertise - to some extent it depends on what degrees they have, or other relevant experience in the subject,” he says.

Hughes at Mossbourne agrees subject knowledge is a challenge, but makes the point that “primary teachers can have degrees in a variety of subjects” and that as a headteacher you should take each one on a “case-by-case basis”.

“I would recommend you align their subject to their area of expertise,” says Hughes. “You might find yourself faced with someone who has a Classics degree but would be the perfect fit to teach music. Degrees aren’t the only indication of someone’s suitability to teach a subject.”

On this point, Young makes the argument that offering primary school teachers who have developed a “strong interest” in a subject the chance to teach it exclusively at secondary school could be very appealing.

“For teachers who [have developed] expertise in specific areas of the curriculum, the prospect of a move into secondary teaching could be enticing by way of a challenge,” he says. “[It would be a] departure into new but relevant territories.”

Joined-up thinking

Someone well used to “enticing” primary school teachers is Benedick Ashmore-Short, CEO of the Park Academies Trust, a group of six schools made up of primaries, secondaries and a sixth form.

Ashmore-Short prides himself on having taught “every single year from Reception to Year 13” and strongly believes in the benefits of teaching across phases.

“As a headteacher, I have brought in a lot of primary school teachers into my secondaries,” he says.

One teacher who made that move is Tamsyn van der Meulen. She is a primary-trained teacher who now leads the alternative provision at Lydiard Park Academy, a secondary comprehensive that’s part of the Park Academies Trust.

“My understanding, training and experience with primary-age pupils has been a fundamental building block for the work I do with older students,” she says. “It allowed me to notice gaps in both emotional and academic development.”

She says this has also helped her develop both “professionally and personally” and given her a better understanding of the wider education system.

Of course, this sort of movement is more straightforward in multi-academy trusts where a teacher can change schools without having to change too much else - something Zuccollo says can already be seen in workforce data.

“We know MATs have much more movement between them, so moving teachers between phases in mixed primary and secondary MATs would be very straightforward,” he says.

Ashmore-Short says this is something MAT leaders should take advantage of in their recruitment processes.

“In the spring term, we interviewed for a KS2 primary teacher and had 13 applicants. At the same time, I had a role in secondary for which we had no applicants,” he explains.

Ashmore-Short says he did some “joined-up thinking” and offered “good but unsuccessful candidates the chance to be cross-phase and teach both secondary and primary” at different schools within the trust.

To make this work, he says the trust has put in place a “robust system of support” for the successful candidate - such as pairing them with an experienced subject teacher for their KS3 lessons - and ensuring timetabling works as required.

With the recruitment market in the shape it’s in, Ashmore-Short plans to continue this approach with a strategy to fill vacancies and improve cross-phase planning.

“We have plans to advertise for teachers of KS2 and 3,” he says. “It’s worth it because of the benefits to primaries and secondaries if they work together.”

Incentives to change

Of course, though, convincing teachers in primary schools to move to secondary is not going to be straightforward - not to mention all the new challenges that would bring.

“Looking at the numbers, it seems easy - all these primary school teachers who we could move across. But it will always be more complicated than that,” says NFER’s Worth.

“There will be many who won’t want to switch and swapping to secondary will be a hard sell.”

Zuccollo agrees: “There will be a lot of primary school teachers who do it because they really want to work with that specific age group. They’re not going to be persuaded to make the change, no matter what’s on offer.”

Young says this issue might be particularly tricky with teachers who currently work with younger children. These teachers, he says, would be “very unlikely to consider such a move” - in part because of the “pedagogical differences of approach” between the two phases.

Could one incentive to overcome this simply be the offer of cold, hard cash? After all, we offer bursaries to train, incentives to teachers from overseas and TLRs - so why not do the same for teachers moving phase?

Worth says the idea has merit: “Offering an incentive to primary teachers to go into secondary could be part of the solution because of the pressure on primary teacher supply,” he says.

But Hughes is against putting any money into a scheme to draw primary teachers across to secondary.

“This is a stopgap - putting a finger in the dam,” he says. “The reality is this won’t solve the problem. We need a comprehensive strategy whereby we’re recruiting people into the profession - and we need to make teaching attractive.”

Ashmore-Short agrees, saying he would “absolutely not want to see money put into incentivising teachers” to change phase.

Instead, he argues a far better strategy would be for ITT courses to evolve to offer degrees that “ensure every teacher can teach to key stage 3”.

He adds: “Instead of separate primary and secondary ITT courses, we should train people as educators and allow them through their training and placements to find their space.”

There is, in fact, precedent for this, with Young noting that such courses were commonplace in the 1970s.

Such courses exist now, too, with James Noble-Rogers, executive director of the Universities’ Council for the Education of Teachers, noting that there are ITE programmes that span KS2 and KS3, training teachers for both primary and secondary.

No simple solution

However, these options are the exception, rather than the rule. Any would-be trainee trying to seek one out would find, first of all, that the DfE’s own course search doesn’t allow you to search for them; secondly, there are only a handful on offer across the country.

But should they make a comeback?

David Spendlove, associate dean at the Manchester Institute of Education, says these courses placed “huge demands” on the trainees. He adds that schools were not always sure how best to proceed with applicants holding the qualification - and he is dubious they would fare any better now.

Tes approached the DfE regarding several of the points raised in this piece, including the potential for incentives to move primary teachers into secondary, or whether ITT should change to better prepare teachers for both phases.

A spokesperson said: “There are now 27,000 more teachers in our schools than in 2010 - a rise of 6 per cent. We have created almost 1.2 million school places since 2010, the largest increase in school capacity in at least two generations.

“Populations do change and it is for local authorities, working with schools and academy trusts, to balance the supply and demand of school places, in line with changing demographics.”

Overall, the idea of primary teachers moving to secondary is not a simple solution to the complicated teacher recruitment and retention challenges faced by the system.

But when the standard approaches are falling short - and various trends are converging to make the idea potentially necessary - it seems an idea worth considering, especially as market forces may compel many primary-trained teachers to look at another phase.

For the latest education news and analysis delivered every weekday morning, sign up for the Tes Daily newsletter

topics in this article