Lessons for England from 20 years of inclusion in Scotland

Share

Lessons for England from 20 years of inclusion in Scotland

In Scotland a “presumption of mainstream” has been in place for a quarter of a century, having been set out in law in 2000. The intention was to “strengthen the rights of children with special educational needs to be included alongside their peers in mainstream schools”.

Then the Additional Support for Learning Act of 2004 provided a new, more inclusive framework for identifying and addressing additional support needs (ASN).

For anyone who has been paying attention to the special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) crisis in England - and how the government hopes to solve it - some of this will sound familiar.

Reform of the SEND system

The Labour government has said that it wants more pupils with SEND educated in mainstream schools.

Prime minister Keir Starmer - facing an “avalanche” of councils being at risk of declaring bankruptcy largely because of SEND costs - is talking about urgently reforming the system, moving towards “early intervention” and ensuring that “provision is available in mainstream schools”.

So what can England learn from Scotland’s now relatively long - and unquestionably fraught - experience of trying to make special needs a priority for all schools?

More on inclusion:

- ‘Damning’ report on support for ASN pupils

- SEND reform will be done ‘as urgently as possible’

- ‘Inadequate’ ASN provision having impact on all pupils

Sheena Devlin is the new general secretary of the Association of Directors of Education in Scotland (ADES), having recently left the post of education and children’s services director in Perth and Kinross.

At the beginning of the millennium, Devlin was headteacher of a large inner-city primary school. She recalls that the previous system in Scotland for supporting children with additional needs was about “extraction”. That could have meant removing groups of children from the classroom to be taught by the support-for-learning teacher or sending them to specialist schools.

The changes in Scotland - brought about by the aforementioned legislation in 2000 and 2004 - led to a system that was about “support within the class for the range of different needs”, she says.

They prioritised “reducing stigma”, “better inclusion” and the “nirvana” of children being educated closest to where they lived and played - and not exclusively with other children with disabilities or learning difficulties.

“The whole notion of being a truly comprehensive education system was actually something that was quite serious in those proposals,” Devlin explains.

It is timely to be reminded of the admirable aims behind the original push for inclusion in Scotland, given the number of reports in recent times - the latest published just last week - that have highlighted less comfortable realities.

The battle for support

Yet even though the criticism of mainstreaming - which we will get to - has felt somewhat unrelenting, it is worth bearing in mind that, as the Scottish government has been keen to point out, it still has “broad consensus of support”.

The reform was fuelled by a desire to “do the right thing” both for children with additional needs who were being routinely plucked from their communities to be educated and also for society more broadly, says Scott Mulholland, chair of the ADES inclusion network and assistant education director in South Ayrshire.

Angela Morgan, who was tasked with carrying out a review of additional support for learning (ASL) in Scotland, argued in her 2020 report that all children stood to benefit from inclusion because it showed that “people who are different to them are valued, respected and included”. This then “shapes the beliefs and attitudes [that] will underpin their own contribution as adults”, she added.

However, that same report and others since have laid bare the many challenges.

Children in Scotland in need of extra support in school, and their families, often talk about having to do battle to secure it - and teachers and school leaders are open about the huge pressure they are put under.

The challenge that staff face was epitomised by a teacher who contributed to the 2023 “national discussion” on Scottish education. The teacher said that in a class of 30 they had four autistic children (one also had ADHD and depression), three with longstanding separation anxieties, one who was adopted, one who had a difficult home life and was “experiencing a form of trauma”, one who was a young carer, two with severe learning difficulties and eight with “‘normal’ behind-track difficulties”.

The teacher said they could not give the 12 children with additional needs enough attention to support their wellbeing, never mind the other 18.

Before and since there have been reports with equally damning evidence. The Morgan review found ASL “fragmented and inconsistent”.

Children with ASN - a term seen in Scotland as more inclusive and less stigmatising than “special needs”, which has largely fallen out of use - were not able to “flourish and fulfil their potential”, the review said.

Mainstream school ‘intolerable’

The Scottish Parliament’s Education, Children and Young People Committee’s ASL inquiry found in 2024 that mainstream education could be “intolerable” for many children with ASN because of the gap between policy ambition and implementation. It concluded that “significant issues in relation to meeting pupils’ additional support needs remain”, which “should not be allowed to continue”.

The latest report, by spending watchdog Audit Scotland, was published on 27 February and attributed blame to both the Scottish government and local authorities for failing to plan for more inclusive approaches.

In Scotland, the definition of ASN is broad. A child can be deemed to have an additional support need if they have a learning disability or difficulty such as dyslexia, but also if they are being bullied, have experienced a bereavement, are looked after or if they are particularly able or talented, among other categories.

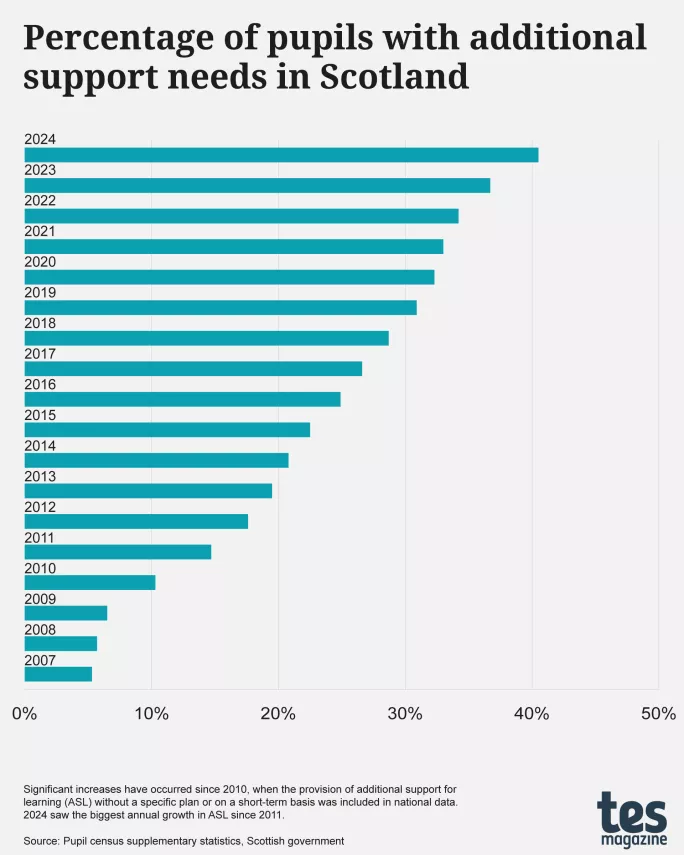

Now 40.5 per cent of all pupils in state schools are classed as having ASN (see the graph above), according to the 2024 pupil census - almost eight times the number when the ASL act was introduced in 2004.

‘Mainstreaming is not a cheap option’

However, Audit Scotland says it is not possible to conclude whether levels of funding and staffing and the staffing mix are “appropriate to meet current needs”.

Its report says that Scottish councils spend around 12 per cent of their education budgets on ASL. In 2022-23, this was £926 million. The Scottish government says more than £1 billion was spent on ASL in 2023-24, with an extra £29 million being invested in specialist staff in 2025-26.

But Audit Scotland seems to imply that whatever the current spend is, it is not enough. It advises that “a key part of ASL improvement” should be “appropriate” resourcing.

Teaching unions are more pointed. The EIS - Scotland’s biggest teachers’ union - says the current level of investment in ASL “is wholly inadequate to cope with the current, and growing, level and complexity of additional support needs”.

All of this should set alarm bells ringing in England, where the hope is that mainstreaming will be a means of saving money.

Everything is relative, however, with central government funding in England for “high needs” totalling nearly £11 billion, according to an Institute for Fiscal Studies report on SEND spending in December. And with a huge deficit in English local authorities’ high-needs budgets - estimated to be at least £3.3 billion in 2024 - the Scottish situation may well look appealing.

Nevertheless, Scotland has a population roughly a tenth of the size of England and over £1 billion for ASL is proving insufficient there.

A changing landscape

Mulholland says saving money was not a driver for the introduction of the presumption of mainstream in Scotland, and warns that mainstreaming should not be seen as a way of reducing costs. Devlin echoes this, saying mainstreaming is “not a cheap option”.

Both point to the adaptations needed to school buildings to make them suitable for ASN children, as well as the extra staff required to support pupils in mainstream schools.

Before the presumption of mainstream, Devlin remembers there were no classroom assistants working in her large primary school. Now there are more than 17,000 employed across Scotland.

As a result of mainstreaming, the education landscape has, in bricks-and-mortar terms, changed significantly: the number of special schools in Scotland has reduced from 194 in 2003 to 107 in 2024.

The rolls of Scotland’s seven grant-aided special schools - which have a range of expertise, from educating visually impaired children to those with social, emotional and behavioural problems - have also fallen.

In 2007 there were 322 pupils in grant-aided special schools, but by 2024 this figure had dropped to 100. While these schools receive government grants, they are still expensive for councils because they need to charge fees to cover all their costs.

Councils, meanwhile, are increasingly providing “enhanced provision” for pupils with ASN in mainstream schools: the Audit Scotland report says 20 per cent of all mainstream schools had some form of enhanced provision in 2023.

Still, demand for specialist places is outstripping supply. Media investigations have revealed that families who request places at special schools often have their bids rejected.

Parents’ disputes with councils

The upshot is unhappy and frustrated parents increasingly turning to the Additional Support Needs Tribunal in Scotland to resolve disputes with councils: Audit Scotland said tribunal applications increased by 67 per cent between 2019-20 and 2023-24.

However, Fife Council told the parliamentary committee’s ASL inquiry that the tribunal process was “enormously expensive”, especially if it concerns a decision to place a child in independent provision.

City of Edinburgh Council said that independent-school placements could cost between £70,000 and £180,000 annually, with pupils often remaining in placement for more than eight years. Such fees were “the main budget overspend in most local authorities alongside transport”.

In 2022-23, 160 of the 202 applications to the ASN Tribunal were in relation to placing requests to schools that were made by parents or children but subsequently refused by councils.

However, challenging the support their children receive has arguably been made more difficult for families because of the very small number of children with a statutory coordinated support plan (CSP).

Academics have long argued that CSPs are an essential means of ensuring that children’s rights are realised, as they are the only education documents with legal force. But while 40.5 per cent of Scottish pupils have ASN, just 0.4 per cent (1,215 children) have a CSP.

‘Schools need the right mix of staff - and staff need the right training’

In England, the opposite appears to have happened. The IFS report on SEND spending says the number of pupils with SEND, and in particular those with the CSP equivalent - an education, health and care plan (EHCP) - has “rocketed” since 2018.

Driving down the number of EHCPs is seen as key to getting SEND spending under control.

But in Scotland, where the number of CSPs is extremely low, Sheila Riddell, chair of inclusion and diversity at the University of Edinburgh, points out that research suggests “many ASN pupils in Scotland receive little in the way of additional support”.

Audit Scotland finds that the most common support for ASN pupils is from the classroom teacher - this has trebled since 2019 - while other forms of support, including from ASN specialist staff, have remained relatively static. The reasons were unclear but could be down to better recording “or more specialist support not being available”.

Mulholland says that for mainstreaming to be a success, schools need the right mix of staff - teachers but also pupil-support assistants, educational psychologists, speech and language therapists, home-link workers - and staff need the right training and professional development.

Devlin says: “If you trained to become a teacher in the 1990s, you’ve got a different landscape in terms of the children and the range of need in front of you now.”

A failed experiment?

In her 2020 report, Morgan said Scotland had to face up to “the deeply uncomfortable fact” that not all professionals “are signed up to the principles of inclusion and the presumption of mainstreaming”.

She found “many dedicated, skilled and inspiring professionals” doing everything they could to help ASN children “flourish and fulfil their potential”. However, some teachers did not see this as their job and others had become “disillusioned” because they had not seen inclusion delivered in practice.

Morgan said “values and beliefs, culture and mindset” were “fundamental” and there was “more work to do in this regard”.

Since the publication of her report, Morgan has warned that the danger now for Scotland is that mainstreaming is declared a failed experiment, resulting in “a swing back to an institutional model for those children that don’t fit”.

In England, the pendulum appears to be poised to swing in the opposite direction.

But for the sake of children, their families and the professionals who work with them, understanding the Scottish experience is vital - with the key message that, while sufficient resources and proper planning are crucial, so is cultural change and the winning of hearts and minds.

Emma Seith is senior reporter at Tes Scotland. She posts on Bluesky

For the latest education news and analysis delivered every weekday morning, sign up for the Tes Daily newsletter and the The Week in Scotland newsletter