Teacher pay: What the DfE’s plans mean for you

The latest information on teacher pay scales is available here: Teacher pay 2022-23: what the salary rises mean for you

The new teacher pay scales have now been updated in the Teaching Pay and Conditions.

Last week the government published its evidence to the School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB) on its proposals for teacher pay over the next two years.

The most notable of these proposals is to boost new teachers’ starting salary to £30,000 - something the Department for Education says is needed to ensure that we have “a high-quality teaching workforce”, and that new teachers are paid at a level that better “reflects” the challenges they face.

It’s not the only pay proposal, though, with others concerning those already in teaching - including in leadership positions - and in different parts of the country.

However, at 130 pages long and with almost 80 separate tables and figures, the DfE evidence report isn’t a document for light reading.

We’ve been through it to pick out the key details. Here we explain what the proposals - if agreed - will mean for current and future teachers.

The DfE’s proposals for teacher pay

A pay increase for teachers on the main and upper pay scale

The plan to increase new teachers’ starting salary to £30,000 will not happen in isolation - teachers on the main and upper pay scales will also see an increase.

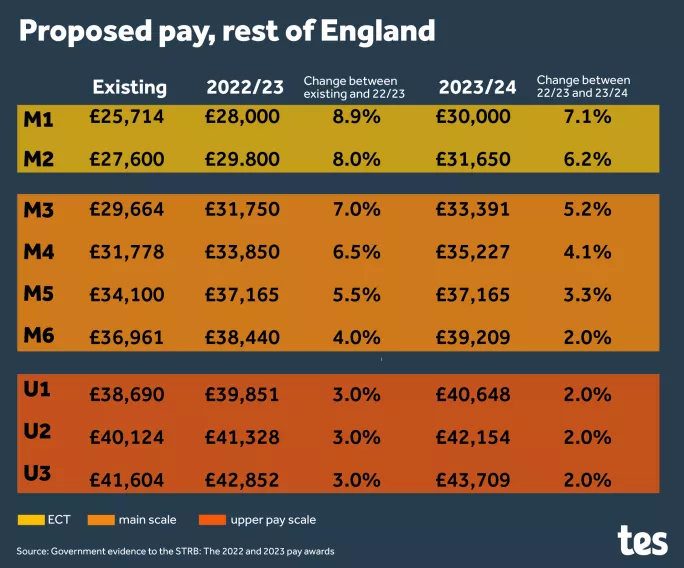

However, these increases are not equal and newer teachers will be receiving larger uplifts - as you can see from the table below.

What this table shows, too, is that the move to £30,000 will not happen in one year but will be spread over two years - although the biggest uplift is set to be implemented in the first year.

Under these proposals, from September 2022 teachers on the main scale would receive increases beginning at 8.9 per cent, while all teachers on the upper pay scale will receive a 3 per cent increase in that first year.

Then in September 2023 salaries would increase again, and the uplift would range from 7.1 per cent to 2 per cent for main scale teachers. The uplift would be 2 per cent for upper pay scale teachers.

The DfE justifies its decision to focus pay increases on those newest to the classroom by drawing on the evidence of the “leaky pipeline” between initial teacher training and the classroom.

It is hoped this money will help to reduce the number of ITT trainees who decide not to go on to teach in a state school in England - currently 27 per cent of all of those who receive an ITT qualification.

However, it isn’t just trainees leaking out of the system. This uplift is also aimed at improving the retention of early career teachers, who will be able to see their earnings increasing if they stick around.

The DfE report notes that only “85 per cent of teachers who qualified in 2019 were still teaching one year after qualification”.

This is a notable attrition rate and it is clearly vital to find ways to keep these teachers in the profession

What these proposals also mean, however, is that those who have been in the classroom the longest will receive the least generous pay increases.

Ian Hartwright, senior policy adviser for school leaders’ union the NAHT, tells Tes that although he welcomes the move to increase the starting salary to £30,000, he is disappointed that the remuneration isn’t equally spread.

“After many years of real-terms pay cuts, including this year’s pay freeze, all teachers and leaders need their pay to be restored,” he says.

“The current suggestion for differentiated pay would mean that higher starting salaries for ECTs are essentially being paid for by lower uplifts for experienced teachers and leaders - making experienced professionals worse off.”

Tom Richmond, the founder and director of EDSK, an independent education thinktank, agrees that this is an issue but says that, given there are “rising wages” elsewhere in the economy, the higher salaries are needed to get more people into teaching in the first place.

“The government is right to prioritise higher salaries for newer teachers, as teacher training applications are currently lower than pre-pandemic levels,” he explains.

Using cash to bring in new trainee teachers is one thing, but will this move keep them in the teaching pool?

Richmond is cautious on this but says the DfE report at least shows that this problem is on Whitehall’s radar. “Although this will not solve the wider recruitment and retention problems, it shows a welcome willingness among ministers to listen to the profession,” he says.

Meanwhile, Michael Tidd, headteacher of East Preston Junior School, in West Sussex, agrees that there is “merit in the argument” put forward the DfE, given the economic reality.

“The greater increases are needed at the lower end of the pay scale, particularly in terms of retaining teachers during those challenging first few years,” he says.

“That’s not intended as a reflection of teachers’ relative worth, but of the reality of retention issues.”

London pay uplift will be lower than the average

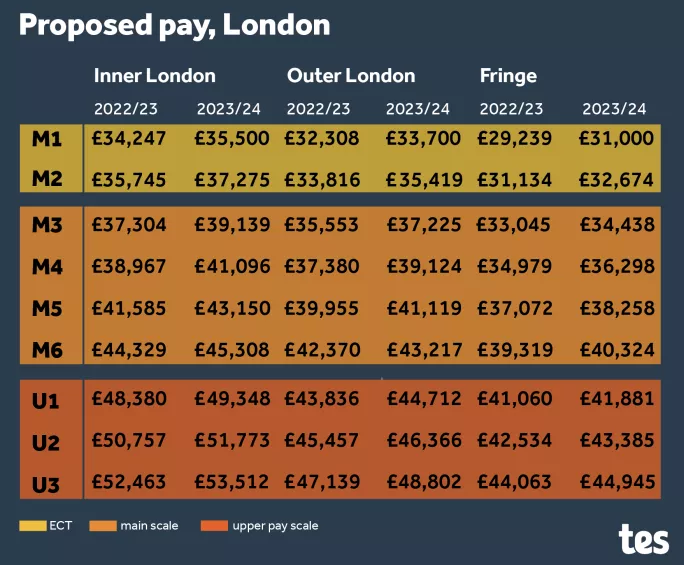

Since 2019, new teachers in inner London have been awarded a salary in excess of £30,000 - but that doesn’t mean they’ve been left out of these plans.

The DfE report proposes that all teachers in London receive salary increases - but at rates not as generous as those in the rest of the country.

The table above shows the proposals for inner and outer London and the fringe areas of the capital, and shows that, while teachers in the rest of England will, in total, receive a 15.3 per cent increase over the two years, teachers in inner London will only see their salary uplifted by 9.8 per cent.

In cash terms, this would mean an ECT in other parts of England would see an increase of £4,286, whereas in inner London ECTs will be taking home an extra £3,343.

Although, of course, the London teacher would still take home a higher amount overall.

The report says inner London pay was “already better align[ed]” with the aims of the reforms.

However, Matt Padley, research fellow at Loughborough University’s Centre for Research in Social Policy and co-director of research for social and policy studies, says the decision to not raise salaries in inner London in line with the rest of the country is perplexing.

“Costs are higher in London, and inflation is as likely to impact people living and working there as it is elsewhere,” he says.

“Therefore, increasing the starting salary in inner London by a smaller percentage than elsewhere? That doesn’t make much sense.”

Padley’s work looks at the income required for a minimum standard of living, and how this amount varies depending on where you live.

He warns that the salary for teachers in inner London is already below what is required to meet the minimum standard of living.

“Using 2021 data, if you live on your own and don’t share accommodation, you need £35,000 to reach the minimum standard of living,” says Padley.

“By 2023 what you need for the minimum would have increased significantly.”

No TLR increases

Unlike senior leaders, middle leaders do not have their own pay scale and are instead remunerated for their work using Teaching and Learning Responsibility (TLR) payments on top of their main or upper pay scale salary.

Although these teachers will receive an uplift in their salary, the report makes no mention of increasing TLR payments, which remain at the same level as 2020.

The report also notes that TLRs are mostly used in secondary schools. However, when geography is taken into account, there is “little difference” in the median amount paid in London compared with the rest of the country.

Not all middle leaders think this is a problem, and some agree that the plans to leave TLRs alone is the right one.

Sana Khalid, a middle leader who works and lives in London, thinks that, if anything, TLRs should be linked to school size, rather than location.

“TLRs could be based on school population, rather than whether they’re in an urban area,” she says.

“Especially when you think about struggling coastal schools, where they find it difficult to recruit. The money would be better used there.”

Smaller pay increases for those on the leadership scale

Unlike classroom teachers, staff paid on leadership scale will only receive 3% uplift to their pay in 2023, and then 2% in 2024.

Along with teachers on the upper pay scale, this is the smallest percentage pay increase in the proposal.

The report justifies this decision by noting that school leaders are staying in teaching at a greater rate than the classroom teachers they manage.

In fact, the report notes that there is a “downward trend” in leaver rates for teachers holding leadership positions.

However, the report does acknowledge that the picture may be more complicated than these figures suggest, and that these numbers may be “masking” problems experienced by schools.

It also makes the point that leaders in schools make a “huge contribution”.

Given this, the report proposes that instead of a pay uplift, school leaders will be able to make use of the “department’s initiatives to support leaders, including a new and updated suite of NPQs [National Professional Qualifications], an additional support offer for new headteachers and a new mental health and wellbeing support package delivered by Education Support”.

The report also says that schools can use “previous pay reforms [to] continue to…reward exceptional leaders”.

Hartwright, though, describes these proposals as “yet another real-terms pay cut for leaders”. He makes the point that “inflation is soaring and due to rise even further” and, as a result, the offer looks even less attractive to those on the upper pay scale and leadership scale.

Kevin Courtney, joint general secretary of the NEU teaching union, says: “Imposing lower increases for more experienced teachers and headteachers is deeply unfair, will damage morale and will actually increase the retention problems already facing the profession.”

However, Sam Sims, a lecturer in the Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities (CEPEO) at University College London and a research associate at FFT Education Datalab, says there is logic in this approach.

There is less risk of more experienced teachers leaving the profession due to pay - as they may struggle to find similar salaries in other professions.

“By the [10-year] point teachers have accumulated specific skills, and by moving to a different profession, those accumulated skills are no longer marketable in a different profession, and consequently the drop in pay to move to a new occupation and start from scratch is quite large,” he says.

In addition to this, Sims says that there is an “identity that starts to solidify - I am a teacher”, combined with the fact that over time teaching becomes easier, and that keeps people in the sector.

The upshot of all of this is that “the longer you stay in teaching, the longer you will stay in teaching”, says Sims, and so the government can get away with pushing pay increases to ECTs and not leaders.

Could this make ECTs less appealing to employ?

The cost of staff is by far the most significant budget consideration for any school, and it is obvious that these changes will impact on the amount that all schools will be spending on staff.

But how might these reforms change decisions made by school leaders on the day of a teaching interview?

Sims says that one unintended outcome could be that the previous logic of employing ECTs due to the cost savings is eroded.

For example, currently, a teacher on U3 is 47 per cent more expensive than an ECT. Once the starting salary is increased to £30,000, that difference drops by 10 percentage points to 37 per cent.

Put in cash terms, your £15,890 saving drops to just £13,709.

Sims makes the point that the decision to uplift salaries of newer teachers across all subjects and phases will mean that ECTs of subjects where there is no shortage, such as history, will see a reduction in their “value proposition”.

“When it comes to choosing between two teachers, one more experienced than the other, then why go for the ECT?” asks Sims.

“There are also non-financial costs of the ECT, such as the reduced timetable. The incentives to employ an ECT history teacher has dropped.”

However, Sims does not believe this will have a huge impact - noting that research has shown “concerns that introducing a higher minimum wage will result in managers investing in more experienced staff” are unfounded.

Padley agrees and says that leaders will still see an ECT as an appealing option.

“Even with the increase, you would be saving over £13,000, and that is still a reasonable difference, so I would be very surprised if raising the bottom would make a difference to recruitment decisions,” he says.

Will this address the recruitment and retention crisis?

The most important question, of course, is whether or not these changes will improve the recruitment and retention of teachers.

Richmond believes that although this is a strong start, the rising costs of living may necessitate further increases to ensure that teaching continues to be an attractive option for new graduates and to retain existing staff.

“The enormous challenge posed by rising inflation means that the government may need to revisit teacher salaries in the near future to prevent staffing issues from getting worse in the coming months,” he says.

From the perspective of a teacher in the classroom, Khalid says she supports the proposed reforms because it is “difficult when you’re a young teacher on a low salary” and there is a need for “young blood” in the profession.

Sims says that after “many years of pay freezes”, teachers deserve a pay rise for their “amazing work”.

He says the DFE’s main proposal has the strength of being simple - but this is also a drawback.

“The proposal is very simple, salient, everyone knows what they’re getting - this is a strength,” he says.

“But in terms of value for money and achieving the goals of getting enough teachers in shortage subjects…[here the] simplicity of the policy is also its weakness.”

Sims points out that for subjects and phases where there isn’t a recruitment issue, you “end up with deadweight loss” because you are paying for things that would have happened anyway.

So is the answer paying teachers different salaries for different subjects - and aiming the biggest rises at those where there is the biggest shortfall?

Sims sees this idea as “demotivating” and says it would be too complicated to implement, given that many teachers will teach outside their specialisms, too.

Yet the government’s report notes that a growing school student population will put more pressure on teacher supply - especially given that by 2023-34 there will be a secondary population 7.6 per cent higher than 2019-2020.

Will this pay increase be enough to get ahead of this problem and ensure that we have enough new teachers for this cohort growth?

Sims believes it will help but questions why it has taken so long to be put into place.

“This is public policymaking by looking in the rearview mirror,” he says. “If this had been introduced a few years ago, we could have dealt with the problem [of teacher recruitment] with no additional cost.”

Julie McCulloch, director of policy at the Association of School and College Leaders, also raised this issue and says the fact that pay was frozen this year was “regrettable” because it has made “recruitment and retention even harder”.

The hope will be, though, that if the new proposals put forward are accepted, schools will have a stronger bargaining chip to entice new teachers into the profession in the years ahead - and then hopefully keep them with the lure of ever-rising take-home pay.

Time will tell if it works.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article