Why getting teacher recruitment right is proving so difficult

Getting the right number of teachers into schools at the right time seems like it should - in theory - be straightforward, observes Graham Donaldson, Scotland’s former senior chief inspector of education and one of the Scottish government’s international education advisers.

After all, we know how many babies are born so we should be able to project school rolls. But actually, getting the right people in the right place has been a persistent problem in Scotland.

On the supply side, “getting the right people in the right numbers” was a chapter in Donaldson’s 2011 landmark tome on how to improve teacher education, Teaching Scotland’s Future, and the problem has continued to flummox not just the Scottish government. While we have been reporting on the growing number of unfilled places on secondary teacher-education courses in Scotland, Tes colleagues in England have highlighted the same phenomenon.

Getting the right number of teachers into the system might be complex but there are some obvious flaws in the way teacher supply is handled by ministers in both countries. We often hear governments being accused of taking sticking-plaster approaches to long-term problems in the public sector, and teacher supply is no exception. When a tipping point is reached - when over- or under-supply becomes too dire to ignore - too often quick fixes are seized upon.

During his time as education secretary from 2016 to 2021, John Swinney - now Scotland’s deputy first minister - was faced with a teacher shortage and took a two-pronged approach: his aim was to get more teachers into the system by making it easier to train to become one, and by turning teaching into a more appealing career.

So far, so sensible. But when the new routes into the profession started to ease the pressure on schools, pressure on the government also eased, and talk of making teaching more attractive and creating more ways for teachers to advance their careers fizzled out.

The issues with teacher recruitment

In 2017, Scotland had grand plans for emulating Singapore and creating myriad routes for teachers to be promoted within and beyond the classroom. By 2021, this amounted to the role of “lead teacher” being quietly introduced, with no fanfare and no additional funding to encourage councils to create jobs.

This one new post to emerge from the Independent Panel on Career Pathways for Teachers - which reported in 2019 - remains, at least for now, something of a damp squib. Over a year on and there are just five lead teachers employed in Scotland, according to the teacher census published in December.

While Swinney moved on to the next crisis hitting the front pages, it was clear that all the government had done was buy itself some time.

So, where is that supply pendulum on its trajectory just now? Do we have too many teachers or too few? This is where the second complexity of the recruitment picture resides: it’s not just about working to get more teachers into the system, but getting the right teachers in the right subjects in the right places. Blanket teacher recruitment drives are a blunt instrument.

So, what do you find if you dig deeper? The statistics on the proportion of new teachers getting work after completing their probation reveal some interesting findings.

The data makes it clear that getting a job in a primary school is particularly tough just now - although there is evidence that very remote and rural areas are simultaneously struggling to recruit. One rural primary headteacher describes recruitment as “a nightmare” - she had more than half a dozen candidates lined up for a maternity cover but all but two withdrew ahead of interview because they “realised how far away we are”.

- News: Sturgeon grilled over how many teaching posts will be cut

- New career route: Only five “lead teachers” working in the whole of Scotland

- Teacher strikes: Councils hit out at government “breach of trust” over teacher pay

Still, she says that there are “lots of excellent young teachers out there without jobs” - even if many see relocating to her area as a bridge too far.

So, why are those teachers not finding work? Part of the problem, she believes, is teachers “job blocking”: those who would have “retired early in the days when it was financially viable” are no longer doing so.

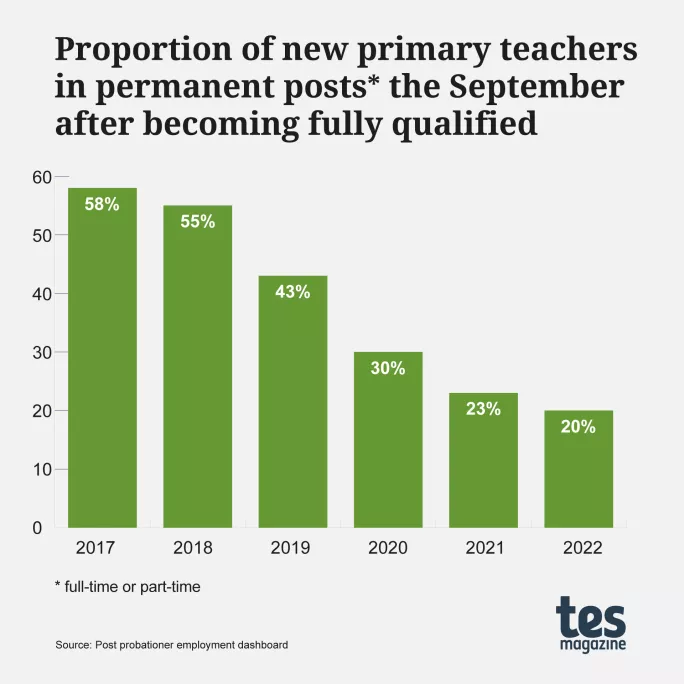

Last year, just one in five newly qualified primary teachers had a job the September after becoming fully qualified - so in their first year as fully fledged teachers just 20 per cent of new recruits had a permanent full-time or part-time post. That’s down from 58 per cent in September 2017.

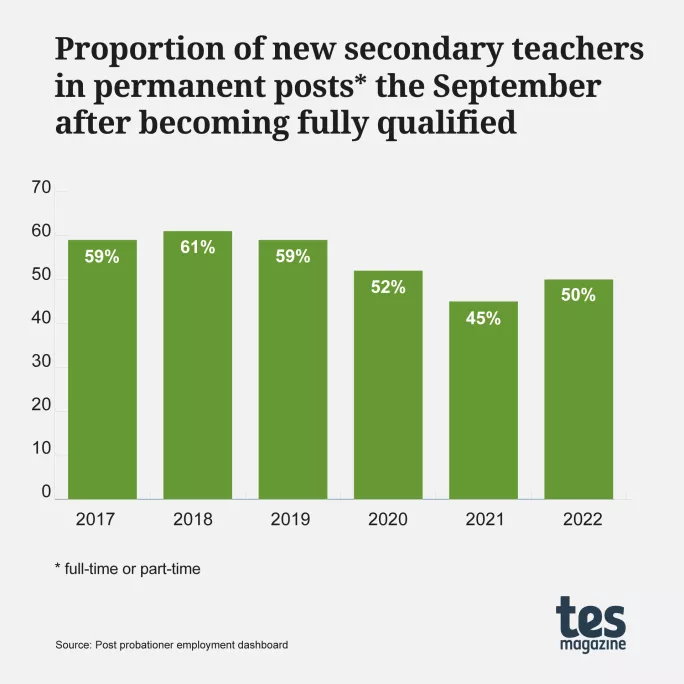

The picture is better for secondary, but the prospects for new starters in this sector have also worsened of late. Last year, half of newly qualified secondary teachers had permanent posts the September after becoming fully qualified, compared with 59 per cent in September 2017.

For shortage subjects such as home economics, that proportion rises to 75 per cent. But if a teacher qualifies in geography, art and design or biology, steady work will be tougher to find: only 32 per cent of geography and art and design teachers who completed their probation in 2021-22 had a permanent post by September 2022.

So, sector and subject strongly influence job prospects - as does location. But the figures on post-probationer employment, as well as telling us where the problems are today, also show us that it hasn’t always been this way.

For comparison, we can look back to 2017 and the proportion of new recruits to primary and secondary teaching that secured work after becoming fully qualified. Those statistics demonstrate that it used to be easier for new teachers to secure permanent contracts, but the figures are also interesting for another reason: in 2017, roughly equal proportions of primary and secondary teachers secured a permanent full-time or part-time contract (58 per cent against 59 per cent). Now, of course, the figures suggest prospective primary teachers are going to find it harder to secure work. So, why is that? What has changed?

Essentially, the government’s policy to increase teacher numbers has collided with the current reality of council budgets - and new teachers frequently suffer as a result.

Blanket teacher recruitment drives are a blunt instrument

Primary school rolls in Scotland are falling and usually intakes on to teacher-education courses would drop to reflect this, but university targets have been kept artificially high so that the government can realise its promise to increase teacher numbers by 3,500 during the 2021-26 Parliament.

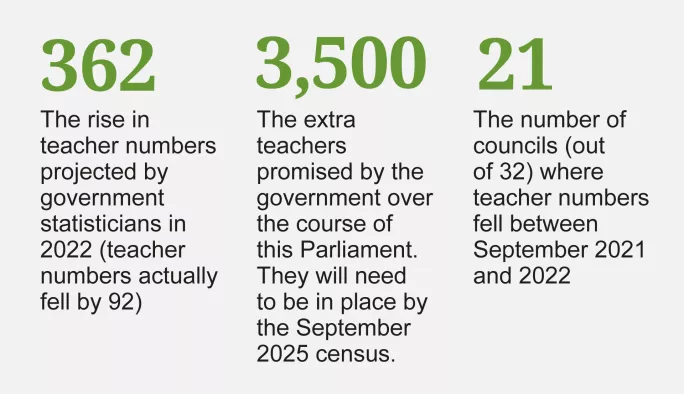

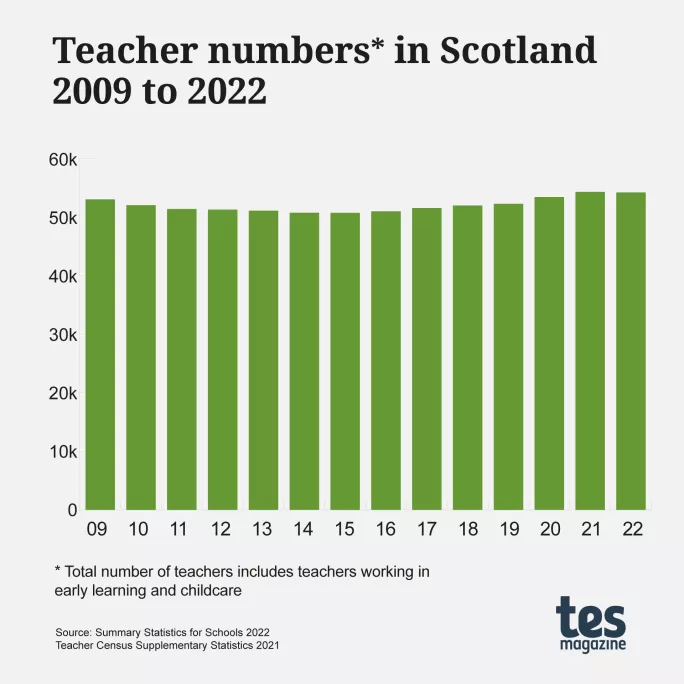

The government must have those staff in place and working in schools by the September 2025 census, but already the modest increase in teacher numbers expected in last year’s census - a first step to hitting the 3,500 target - has not come to pass.

Papers that went to the government’s teacher workforce planning group last year showed that it was expecting “a modest increase of less than 400 teachers in 2022 compared to the 2021 total”, but when the teacher census was published last month, the number of teachers employed in schools had actually fallen by 92 - the first drop in teacher numbers since 2016.

Impact of council budget cuts

The stumbling block is straightforward to explain: it is for councils to employ teachers, and they say they can’t afford to hire more in the midst of a £1 billion funding shortfall.

This month, Moray Council leader Kathleen Robertson said that even “the delivery of the most straightforward, expected services” that councils are responsible for, including education, are “under threat”. Then, last week, Glasgow City Council savings plans were leaked to the media: if all proposed education cuts went ahead, more than 800 teacher jobs and 100 support-for-learning jobs would be lost. One Glasgow proposal is to end the school day early on a Friday, affecting 324 roles, for a saving of £18.5 million.

Of course - as first minister Nicola Sturgeon was keen to point out when grilled over the planned cuts in Parliament on 19 January - these proposals will not necessarily come to pass.

And yesterday she confirmed that the government is planning to ensure that they don’t. During First Minister’s Questions, Ms Sturgeon said the government intended “to take steps to ensure that funding we are providing to councils to maintain increased numbers of teachers actually delivers that outcome”. She added that education secretary Shirley-Anne Somerville would “set out more details to Parliament in the coming days”.

The EIS teaching union welcomed the intervention but said that the government needed to fund councils better.

It is possible that the small drop in teacher numbers between 2021 and 2022 could be quickly turned around by a government cash injection. As Donaldson says: “The more confident councils are in their budgets, the more permanent contracts there will be. That is an iron law.”

Another government pledge - this time to reduce class-contact time by 90 minutes a week - also makes it likely, if the policy is delivered, that demand for teachers will grow.

Lack of job security

In the meantime, there is already a growing surplus of teachers for whom the current lack of jobs has very serious real-life consequences.

Josh LaBrash finished his probation in 2019 and tried to get a permanent post as a secondary geography teacher, but instead “jumped from maternity cover to cover and spent time on the supply list”. Eventually he “got fed up with the lack of job security”, which was preventing him from getting a mortgage. He joined Police Scotland last year.

He feels “let down by the system” and says he would have “loved to have continued teaching”, but he is happy to have found his new career.

Having completed an intensive 12-week training course with the police, he is now in a two-year probation period. Providing he works hard and toes the line, he has “a job for life”; the contrast with teaching is not lost on him.

Bethany Macfarlane is a primary teacher in Biggar. She trained to become a teacher in Carlisle but carried out her probation in Scotland via the flexible route, which essentially means she had to rack up the required hours in the classroom in order to become fully qualified the old-fashioned way, instead of via the Teacher Induction Scheme, which guarantees Scottish teaching graduates a probationary job in a school for a year.

For four years, she has been seeking work in the surrounding authorities - South and North Lanarkshire - but also areas that have often struggled to find staff, including Dumfries and Galloway and the Scottish Borders.

After a series of temporary contracts, Macfarlane has been out of contract since October and is working as a supply teacher at the same time as self-funding an MEd in inclusive education to make herself more employable. She is also pregnant but doesn’t qualify for maternity leave because of the gaps in her work history.

“We’ve been trying for a baby for three years and have had several miscarriages. Timing a family isn’t practical at all when jumping from council area to council area on temporary contracts. I’m left with no maternity leave and no job to return to,” she says.

Macfarlane’s experience of struggling to find work in areas that have typically struggled to find staff is echoed by Jennifer Lilley, who is in her seventh year as a fully qualified teacher. Lilley worked in Glasgow until October, when she gave up her permanent, full-time post and moved to Highland, where she has had supply work every day but not a whiff of a permanent post.

The struggle to attract teachers to rural schools

Data shows that rural authorities are finding recruitment worse in the secondary sector than in primary schools.

Argyll and Bute Council had the biggest proportional decrease in teacher numbers last year, losing 5 per cent - or 45 teachers - between 2021 and 2022. The council says that it has “filled a number of posts since the census” but that the drop was essentially down to “a decrease in our primary school roll” and a commensurate drop in teachers.

Dumfries and Galloway Council saw teacher numbers fall by 4 per cent between 2021 and 2022, equivalent to 51 full-time teachers.

‘The demands put upon teachers as a result of the pandemic act as a disincentive’

It says this was “partly explained by a falling school roll within the primary sector over the past five years, which has led to a reduction in the number of classes”. Secondary schools were “significantly over their staffing entitlement” but “through prudent resourcing decisions…are now back on budget”.

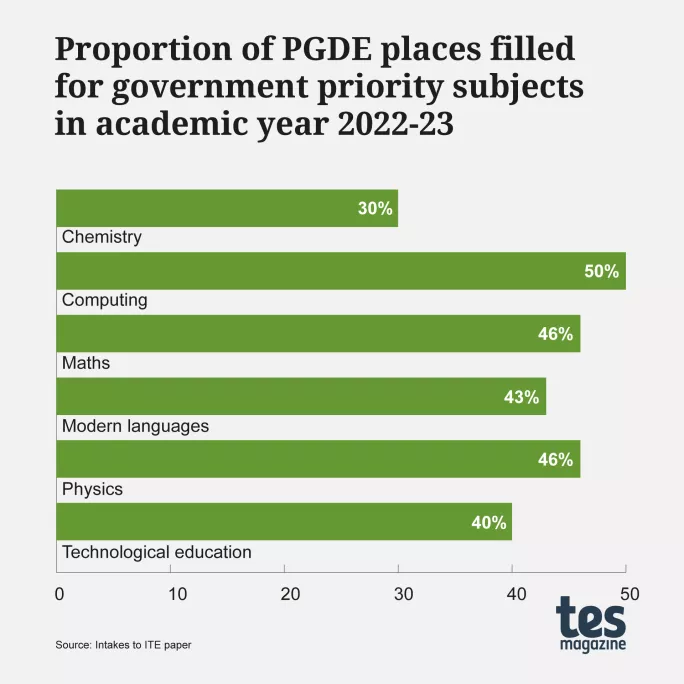

However, some Dumfries and Galloway Council teaching posts continue to attract “a very small number of applicants”: “especially challenging” are computing, technical education, modern languages, home economics and mathematics.

Recently a Liberal Democrat freedom-of-information request revealed that at least 636 teaching posts had to be readvertised in Scotland last year. Dumfries and Galloway readvertised 86 posts but it was Aberdeenshire Council that had the highest number, at 92. A vacancy for a teacher of technical education at Alford Academy was readvertised 11 times; a technical education role at Ellon Academy was readvertised seven times; and a maths job at Banff Academy was readvertised six times.

Selling teaching as a career

If the profession is to stand a chance when competing for science, technology, engineering and maths (Stem) graduates, there needs to be more focus on making teaching an attractive career, believes Professor Margery McMahon, head of the University of Glasgow’s school of education and chair of the Scottish Council of Deans of Education.

This brings us back to Swinney’s two-pronged approach to teacher supply - he wanted more flexible routes into the profession, as well as a better experience for staff once they were in the job. But, of course, the second part of the plan never really came to pass.

However, making teaching more attractive - and more valued in wider society - is important when you can’t compete on salary, says McMahon, which is especially true when it comes to maths and computing graduates.

“We’ve got a bit of work to do on how we promote teaching and advertise it,” says McMahon. “Not advertising in the crude sense but in the way we talk about teaching and value the work of teachers. It’s about restoring that professional status in the wider psyche and wider society.

“I’m worried that the demands put upon teachers as a result of the pandemic act as a disincentive to attract people into the profession. Because the demands were huge.”

Peter Bain, a headteacher and vice-president of School Leaders Scotland, also thinks that reputational damage has been done to teaching in recent times because there is “an ever-increasing belief that behaviour in schools has reached an intolerably poor level, and no one wants to work in a school where they believe they will receive verbal or even physical abuse”.

He says this perception is exacerbated by social media but that, by and large, the reality is that “the majority of schools across the country are wonderful places to work” and that teaching is “an enjoyable and rewarding profession - albeit with a lot of necessary hard work thrown in”.

’Pay is obviously a big factor, but it’s also about conditions’

McMahon, meanwhile, says she keeps asking “what happened to the [2019] career-pathways report?” because, she believes, its proposals had the power to make teaching more appealing.

“I would want us to make sure we don’t lose sight of the career-pathways report. Pay is obviously a big factor and now it’s part of the industrial dispute, but while pay is a big factor, it’s also about conditions,” she says.

“What the career-pathways report offered was enhanced conditions for teachers in Scotland. I would single out, for example, the sabbatical scheme to support career development. It offered a way for teachers to engage beyond their school and take time out for their own development, and it’s those factors that we see in other systems that really do seem to be welcomed by teachers.”

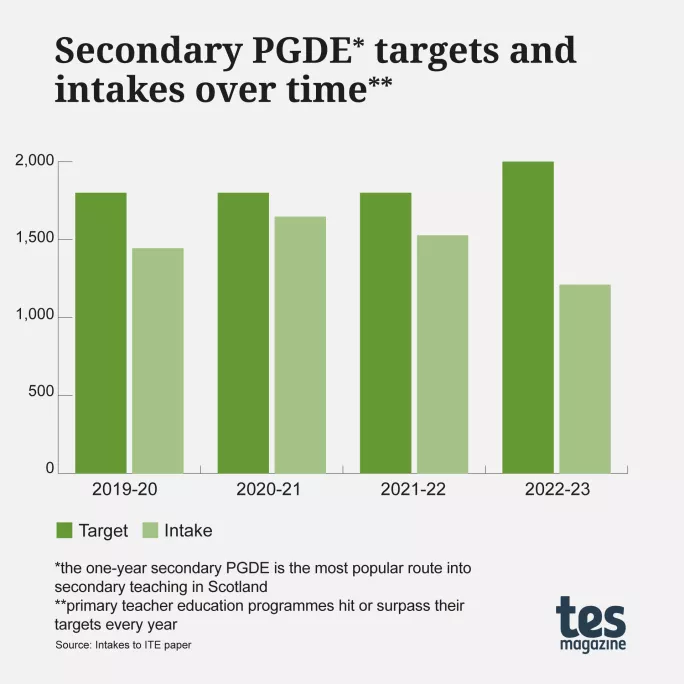

McMahon, of course, has a vested interest in this. While primary teacher-education courses hit their recruitment targets or were oversubscribed this year, Scotland’s teacher-education institutions have struggled to fill places on the one-year secondary PGDE - the most common way to train to become a secondary teacher in Scotland.

Just 61 per cent of places were filled this year, down from 85 per cent last year and 92 per cent the year before. Now, universities face the prospect of the Scottish government clawing back funding for the unfilled places.

The will of ministers to fix recruitment

Rather than teacher supply being an impossible-to-solve conundrum, successive governments have never convinced us that they have the will to solve the problem.

Now, though, teaching is in the limelight for the wrong reasons, as teachers strike over pay, casting doubt on whether the terms and conditions offered in Scotland represent an attractive career. And this is happening at a time when the profession is in danger of losing one of its most appealing attributes: job security.

All of which leads to two key questions. Firstly, how quickly could under-supply in some secondary subjects turn into a teacher recruitment crisis across the board?

And secondly, this: is a crisis actually what is needed for the government to solve teacher supply problems once and for all?

Emma Seith is senior reporter at Tes Scotland. She tweets @Emma_Seith

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters