The scale of the teacher retention crisis revealed

Imagine a class of 100 graduating teachers, fresh-faced and eager to inspire young minds in classrooms up and down the country.

In reality, 11 of those will have left the state-funded sector after just one year of teaching. After three years, 26 will have left. After five years, that number becomes 33. And 10 years after qualifying, 42 of that initial class of 100 will have left.

It is well known that there is a crisis in teacher recruitment and retention. However, when broken down year by year, the new Department for Education workforce figures (based on census data from November 2023) are stark.

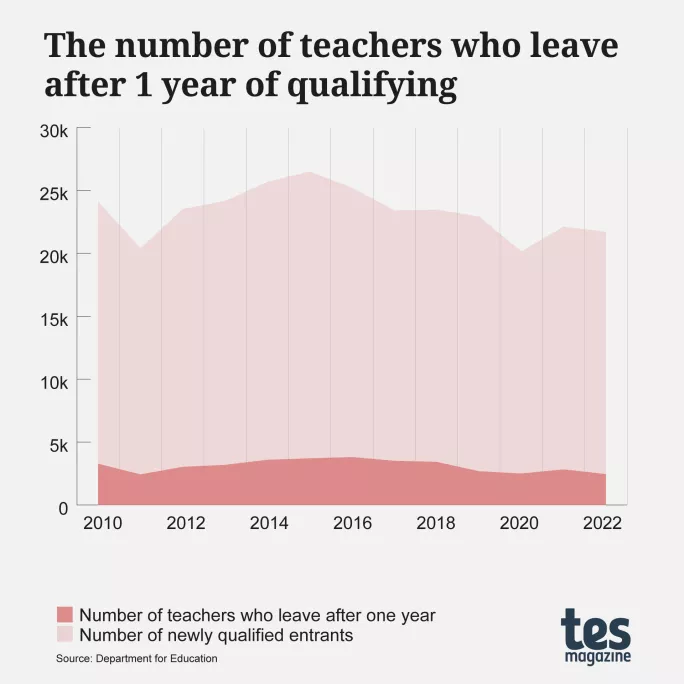

For example, of the 21,705 new teachers who qualified in 2022, 2,453 (11.3 per cent) left after just one year.

This sounds high but it is actually one of the lowest one-year leaver rates since records began in 2010. By comparison, the worst rate came in the 2016 qualifying cohort, when 15.1 per cent (or 3,806 of 25,203) left within one year.

Overall, the effect of sustained low retention is significant. Between 2010 and 2022, 40,438 qualified teachers left the state sector within a year of starting, as shown in the graph below.

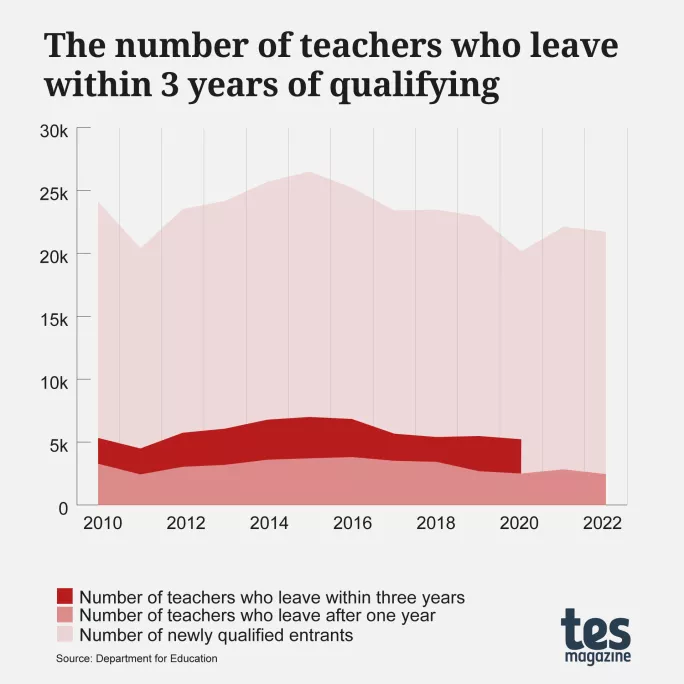

Low retention is not just a problem for teachers in their first year, as more teachers continue to leave during their initial few years.

For example, of the 2020 cohort of 20,150 qualified teachers, after three years, 5,219 (25.9 per cent) had left.

This represents something of a middle point, from a high of 27.1 per cent (6,830 of 25,203) who had left within three years of qualifying in 2016, to a low of 22 per cent (4,489 of 20,405) in 2011.

In total, this means that between 2010 and 2022, a total of 63,977 teachers left within three years of qualifying.

It is worth noting that this figure doesn’t include those who qualified in 2021 and 2022 because this data is not yet available, but based on past trends, it is likely to be similar.

If we map this onto our graph, it’s clear how high the scale of teacher leaver rates starts to become.

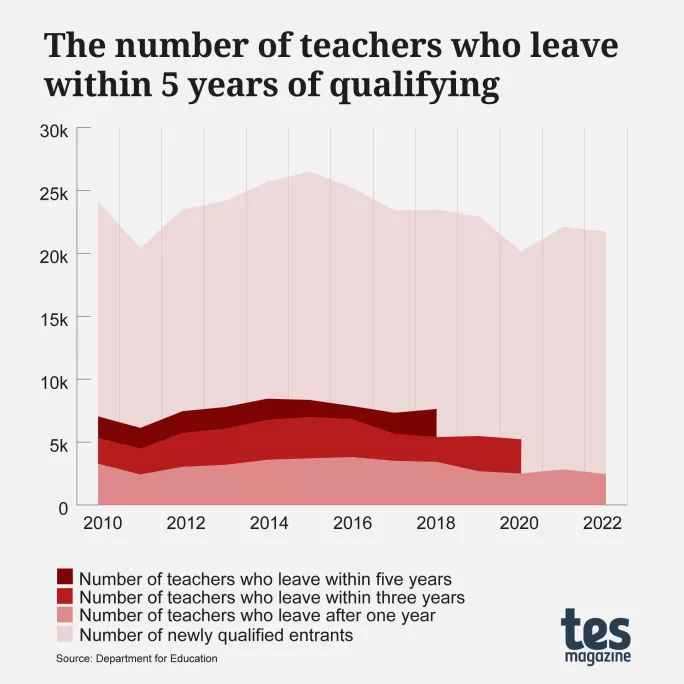

Things don’t get much better as the years go on.

For example, from the 2018 cohort, 32.5 per cent had left after five years, representing 7,627 of 23,469 qualified teachers - a trend that was similar to the years before as the graph below shows.

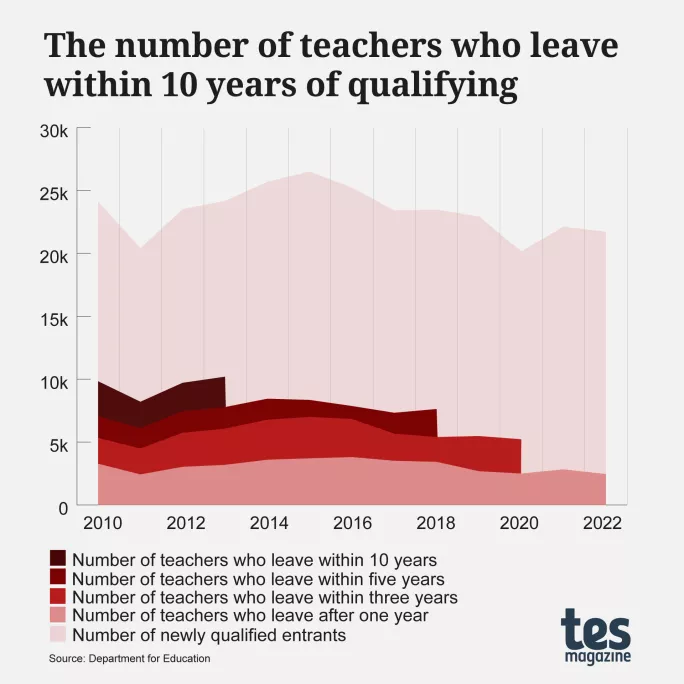

Finally, by the time we reach data on teachers a decade on from qualifying, 42.2 per cent have left the state sector. From the 24,159 who qualified in 2013, just 13,964 remained 10 years later, as shown below.

While some of those leavers will have gone to work internationally or in independent schools, lots will have left teaching entirely. So, what’s going on?

The frontline reality

Emma Hollis, chief executive of the National Association of School-Based Teacher Trainers (NASBTT), says one key issue is that many early career teachers experience a “dissonance” between what they expect when they apply for initial teacher training and “the reality when they enter the classroom”.

“Primary school teachers often go into teaching with a motivation to develop young people holistically, and secondary school teachers are generally excited by the opportunity to deliver the subject they are passionate about,” she says.

“Yet they end up number crunching and dealing with a host of other issues.”

These “other issues” stem in large part from the “closure of wraparound services”, which means we are asking teachers to be “social workers and mental health professionals...this is not going to attract people to and keep people in the profession,” says Hollis.

What’s more, Pepe Di’Iasio, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, says the three- and five-year data makes it clear that other major issues cause many to give up on the sector even if they weather the first year or two.

“Poor retention rates are chiefly the result of excessive workloads and uncompetitive pay compared with other professions,” he says.

Di’Iasio notes, for example, that overall teacher “pay has been cut in real terms since 2010 by a series of government-imposed, below-inflation pay awards” and says while the 6.5 per cent pay award last year was a step in the right direction, “there is still a long way to go”.

Meanwhile issues such as stress caused by Ofsted inspections - as noted in a recent poll by the NEU teaching union - could also be contributing to many teachers’ decisions to leave the sector.

Vacancy rates

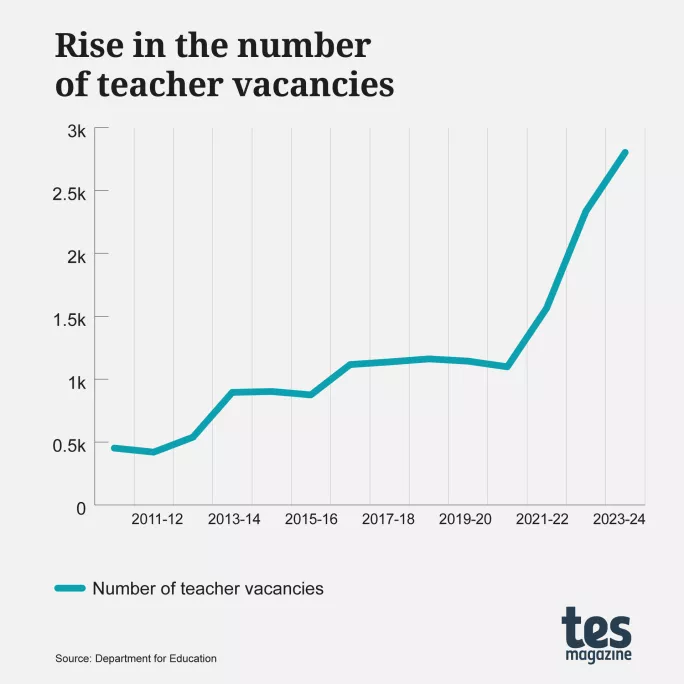

The impact of this ongoing loss of teachers in the early stage of their careers - combined with stalling recruitment rates - is also one likely cause for the rise in teacher vacancies.

Specifically, between November 2022 and November 2023, teacher vacancies increased by 20.1 per cent, from 2,334 to 2,802. This is more than double the 1,098 vacancies open in November 2020, as illustrated in the graph below.

Jack Worth, lead economist at the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER), says the huge increase in vacancies is “all the more surprising” as November is a “very strange time for a normal school to have a vacancy”.

He says that “most vacancies are filled during the main recruitment window during the spring, ready for September”.

Worth says this “suggests that schools are finding it more difficult to fill these vacancies” and many schools are having to take drastic action as a result.

“They may be deploying more non-specialist teachers or even unqualified teachers, and that may have a negative impact on the quality of education that pupils are receiving,” he adds.

Given this, if retention could be improved by even 10 per cent at each stage, these vacancies would be far easier to fill and ensure high-quality education for all - something Di’lasio of ASCL says must be a major post-election priority.

“The new government must get to grips with these issues and it must do so quickly because many schools are increasingly struggling to put teachers in front of classes,” he says.

Glimmers of hope?

How, then, could they do that?

Worth at the NFER suggests there are glimmers of improvements that can be built on. For example, the reduction in the number of teachers leaving within one year seen in the most recent data could be attributed to the government’s 2019 recruitment and retention strategy, “particularly the introduction of the Early Career Framework (ECF), to recognise that teachers in their first couple of years require support and more time to work on their practice”.

He adds that the introduction of a £30,000 minimum salary - announced in 2019, but delivered in 2023 - likely also helped first-year retention. “It has meant that the pay of early career teachers has grown a lot faster than the pay of more experienced teachers,” he says.

Hollis at NASBTT adds that the two-year CPD entitlement for new teachers is an improvement on what came before and may be a cause for the slight retention progress - but she says more research would be needed to know for certain.

However, Ian Hartwright, head of policy at the NAHT school leaders’ union, is less impressed. He says these changes haven’t “moved the dial” enough and describes the ECF as “over-prescriptive”.

“The number of newly qualified teachers leaving the profession is simply too high,” he adds.

Ellen Peirson-Hagger is senior writer at Tes

For the latest education news and analysis delivered directly to your inbox every weekday morning, sign up to the Tes Daily newsletter

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters