Why is France so good at keeping its teachers?

It’s well known that there is a teacher retention crisis in England. But new data on the state of teaching globally sheds light on just how bad it is.

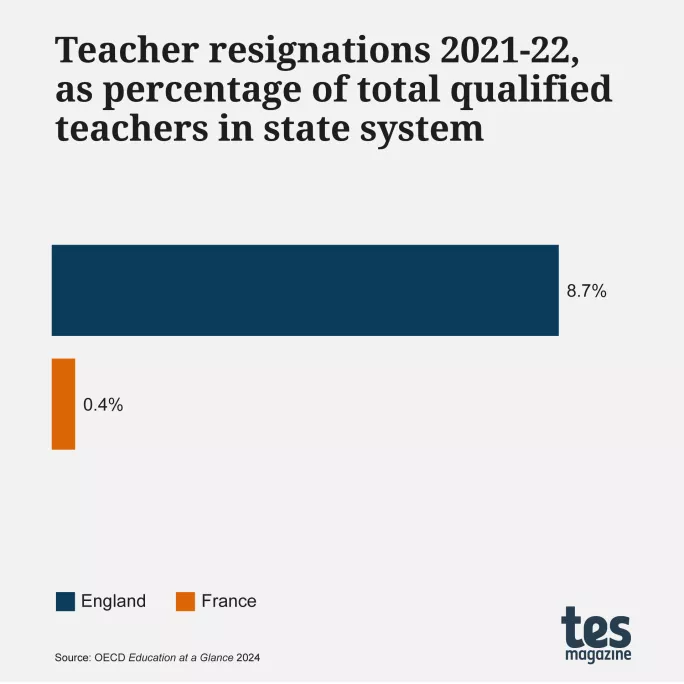

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s latest Education at a Glance report, 8.7 per cent of teachers in England resigned from the profession in 2021-22.

That’s almost double the 4.6 per cent average of the 15 countries surveyed.

And it’s more than 21 times the teacher resignation rate in France, which stood at an impressively low 0.4 per cent in the same academic year.

So, what’s so different about the French school system that makes it better at keeping its teachers, and could England learn something from our colleagues across the Channel?

First things first, the workforces differ by size.

There were 709,435 titulaires - qualified teachers - working in France’s public system in 2021-22. This represents just over 1 per cent of the population.

In England there were 465,526 full-time equivalent teachers in the state sector, representing a little over 0.8 per cent of the population. So already, England is on the back foot.

The concours

Éric Charbonnier, an OECD education analyst who worked on the report, tells Tes the situation in France “is better than England”, but adds a caveat: “The two countries are very different.”

Emilie Caux, who teaches in the French state system, agrees, pointing to the teaching qualification as one major difference.

The content of the concours exam is “not that difficult”, Caux tells Tes. But to pass it you must rank in the top portion of applicants owing to a limited number of available teaching positions.

Caux says that when she took her concours eight years ago, there were 1,500 applicants and just 570 positions. “You have to be at the top if you want to be selected.”

Cyril Guinet, a French teacher at the British School in Paris, adds that the competitiveness of the concours means those who “go for it” typically choose to stay in teaching “for a lifetime”.

Caux adds that once a teacher leaves the state system, “you lose your concours, which makes it very difficult for teachers to contemplate different careers” because returning to education would mean having to take the concours again. “It’s a deterrent.”

The same is true the other way round: once a teacher is in, it’s difficult for the state to remove them owing to the security offered by French public service roles, says Nicholas Hammond, headteacher of the British School of Paris.

“The French teaching population is highly unionised and extraordinarily well protected,” he says. Teaching “is a job for life if you want it”.

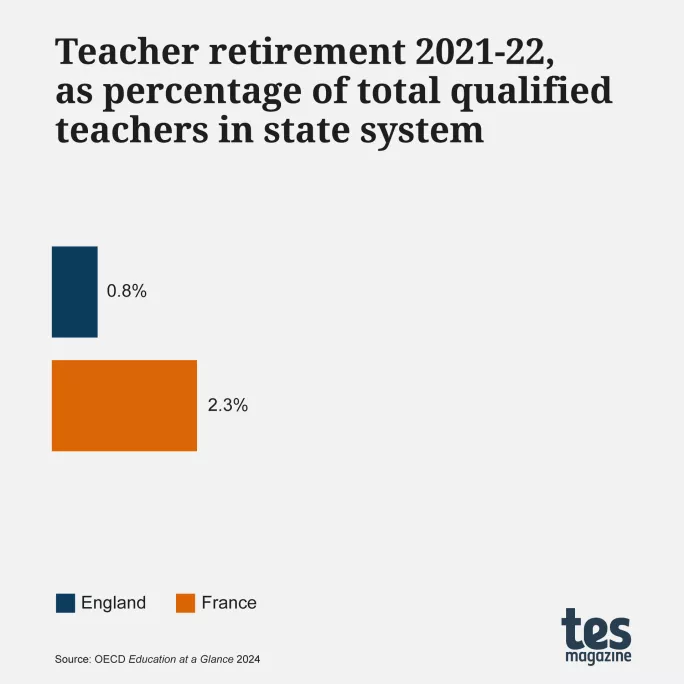

And the data shows that lots do stay for life: 2.3 per cent of France’s teaching workforce retired in 2021-22, compared with 0.8 per cent in England.

The money question

Given the frequent discussion about poor teacher salaries in England, it would be natural to imagine that teachers stay in the profession longer in France because they are paid better.

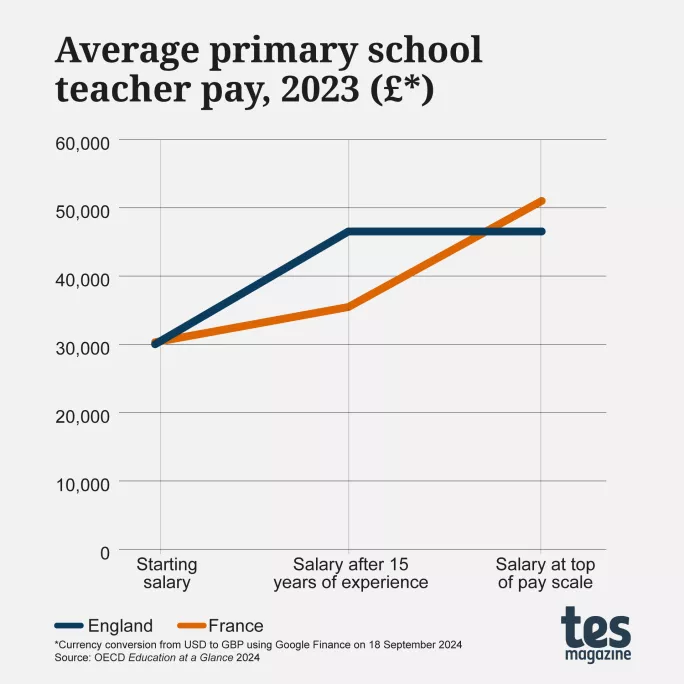

OECD data shows that the picture is more complicated. As Charbonnier explains, “salaries rise very quickly in England, but stagnate after 10 or 15 years in the profession”.

“In France, salaries rise very slowly, but there is a boost at the end of the career, which sometimes motivates people to stay on.”

For example, according to the OECD, the starting salary for primary school teachers is $40,068 (roughly £30,311) in France and $39,677 (roughly £30,015) in England - broadly comparable.

However, after 15 years, a primary teacher in France will be on $46,886 (£35,469), while their contemporary in England will have jumped up to $61,511 (£46,533).

Things change again in the longer term: in France the top end of the pay scale for primary practitioners is $67,423 (£51,006). Meanwhile in England, the top level remains $61,511 (£46,533), so after 15 years, there is no financial incentive to stay longer in the same role.

But on the whole, teacher pay is not deemed “good” in France: “I don’t know how they can justify such low salaries,” says Guinet. So the answer to why retention is far better in France than in England is not simply explained in terms of pay.

- The scale of the teacher retention crisis revealed

- Have new teacher training reforms helped retention?

- Teacher secondments ‘could boost Gen Z recruits’

A different inspection system

Instead, Hammond suggests it has more to do with the comparative lack of stress associated with teaching in France.

Research has shown that 72 per cent of teachers in England have considered leaving the profession because of the “negative impact” of Ofsted. But in France “the inspection culture doesn’t exist in the same way”, Hammond says.

Caux explains that instead of schools being inspected, in France it is teachers who are audited. “They inspect us individually at three points during a career.”

And while she notes that “the pressure is definitely on” on those three occasions, teachers are given a month’s notice ahead of their inspection.

This is far from the “looming Damocles’ sword sort of inspection” that consumes the staff of a whole schools in England as they wait for the dreaded call from Ofsted, Hammond says.

France doesn’t have “a league table culture”, which also lessens pressure on teachers, he adds.

Time well spent

What’s more, Guinet points out that the average secondary teacher in France is required to spend 20 hours teaching and is not expected to be on site outside of those hours.

“I teach 20 hours [in the British School] as well,” he says, “but I’m on site 40 hours a week.”

Compare that with his wife, a teacher in the French system, whose 20 hours are timetabled across four days, leaving one day where she is not required to go into school at all.

This makes it more feasible for teachers to have caring responsibilities at home, he says. “I know my wife was really happy to have a Wednesday to look after the kids.”

Also, teachers in France “don’t mark books”, Guinet says, “they only mark exams” - a practice that, if implemented in England, would almost certainly reduce the “unmanageable workloads” that lead teachers in England to leave the profession.

But according to Caux, the biggest difference between the French and English education systems relates to pastoral care.

“In England, you look at the student as a whole person,” she says. “In France, we are only supposed to look at their brains.”

Guinet concurs. “The word ‘pastoral’ hasn’t made it to France yet.”

Of course, there are many teachers who provide students with care beyond what is expected, he says. But the fact that they are not expected to relieves pressure.

Hammond agrees, adding that this is possible because “the frameworks around schools work more efficiently” than in England. If a teacher feels confident that a child experiencing mental health problems will be seen quickly by their GP, they take on less of the responsibility themselves.

This is in stark contrast to teachers in England, who are increasingly having to take on extra responsibilities almost akin to social workers or child psychiatrists because cuts have seen capacity in those areas significantly reduced.

The grass is always greener

Clearly, there are ways in which France’s system seems more attractive to teachers than England’s. But that hardly makes the French arrangement perfect.

While acknowledging its upsides, Caux says “the system in France is quite broken as well”, and that the country also faces teacher shortages.

Charbonnier adds further context to the resignation numbers, explaining that while “around 3,000 of the 900,000 primary and secondary teachers resigned in 2022 […], there were only 1,000 teachers in this situation in 2016”. Things, therefore, are getting worse.

Teachers in France recently took part in strike action, walking out in protest at the introduction of standardised assessment at primary level.

“Teachers,” Charbonnier explains, “are afraid it will be used to assess them.”

Compare this with the five statutory primary assessments in England, and one thing is clear: in countless ways, the French and English school systems are miles apart.

Ellen Peirson-Hagger is senior writer at Tes

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article