Teacher training data: Regions, race and missing teachers

Last week, the Department for Education (DfE) released the latest data on the 2020-21 cohort of individuals on initial teacher training (ITT) courses.

This was the cohort that was boosted by the impact of the pandemic, as thousands more people than usual saw teaching as a viable career route amid the uncertainty of Covid-19.

But has this boost helped offset concerns about teacher shortages or does a shortfall remain? And what other interesting insights can we glean from the data?

13,000 shortfall from original trainee cohort

Overall, in September 2020, 35,371 postgraduate students started their ITT courses - an increase of 6,057 on the previous year.

Of these, 16,675 attended a course at universities and 18,696 attended school-centred ITT (SCITT) courses.

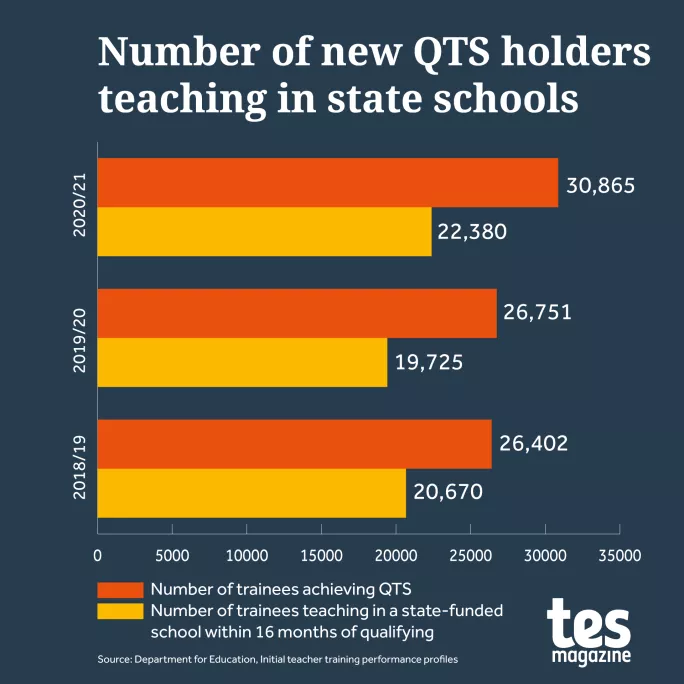

However, by July 2022 - a year after their course had ended in the 2021 academic year - the DfE data showed only 30,865 had achieved qualified teaching status (QTS), meaning 4,506 trainees were still to complete their course.

Of these, the DfE tells us five per cent (1,597) failed to complete a course, while eight per cent (2,909) had yet to complete it.

Furthermore, of the 30,865 who did achieve QTS, only 22,380 were known to be teaching in a state-funded school within 16 months of graduating.

So, between September 2020 and July 2022, based on the DfE’s own data, the state-school sector has lost out on just shy of 13,000 potential new teachers - either because they failed their course, didn’t complete their course or didn’t go on to work in a state school.

Given that there is a huge teacher recruitment crisis taking place, those extra teachers would have been handy.

So, why do they fail, pause or end up not in a state school?

In some cases, the answer is easy: of those yet to gain QTS, some simply had not completed their courses at the time the data was gathered. This is perhaps unsurprising when the disruption caused by the pandemic is taken into account.

“Due to the disruption to training caused by Covid-19, a small proportion of 2019-20 and 2020-21 trainees were offered course extensions into the following academic year to enable them to gain adequate evidence of meeting the Teachers’ Standards,” the DfE noted.

Furthermore, some trainees may have paused their courses or may be awarded QTS at a later date and so will not be included in the official figures.

“Trainees who are yet to complete the course will either go on to be awarded QTS, leave the course before the end or complete without being awarded QTS in a later academic year.”

This itself is not new - every year, some trainees fail to finish QTS (rather than actively failing the course) - five per cent in 2019-20 and four per cent in 2018-19. So it is clear that not all of these lost teachers are the result of the pandemic.

However, Emma Hollis, executive director of the National Association of School-Based Teacher Trainers, says one likely reason for the higher number this time around is simply because more people signed-up to ITT during the uncertainty of the pandemic.

“I suspect there were a number of people who thought they would undertake teacher training because they were concerned about the future,” she tells Tes.

However, as the economic situation improved, it may be that many then started to move towards areas they had been more interested in originally.

“There is always a proportion of people who decide it’s not for them - who either don’t complete because they’re not able to meet the teacher standards or because they think, ‘this isn’t what I thought it was’,” she notes.

“That has probably increased because there were more people taking it as a reaction to what was going on rather than it being what they’d always wanted to do.”

Katrin Sredzki-Seamer, director of the National Modern Languages school-centred initial teacher training, adds weight to this theory by noting that some trainees have found the course very hard and not necessarily what they were expecting.

“I know that some of our [trainees] have really doubted their choice to become teachers when confronted with the challenges in schools.

“They find it difficult to adjust to the immense pressure of the training year and the pressures in school.”

Professor Geraint Jones, executive director and associate pro vice-chancellor of the National Institute of Teaching & Education, concurs.

”The figures include more people who chose to give teaching a go - whereas they perhaps would not have in ‘normal’ times - but discovered it to be more challenging than they realised, and that it was not for them”, he says.

However, even for those who were set on a teaching career may, in many cases, have been put off by the workload and intensity of the courses, he says, arguing that the fact a sizeable portion fail to finish in most years shows the need for two-year courses.

“Workload during a one-year postgraduate ITT course is one of the main reasons trainees drop out, and so a two-year course would certainly go some way in helping this,” he says.

“Our two-year part-time route is growing in popularity and is now the only route one school group is choosing for its trainees, for this reason.”

This may also account for why some fail - perhaps with more time they would reach the required standards.

However, Jones says the fact some students do not achieve QTS should be seen as a good thing as it shows providers are upholding standards to ensure only those ready to teach are reaching the classroom.

“For school leaders, there is nothing more frustrating than taking on a newly qualified teacher who is not up to the job and should not have passed QTS,” he notes.

“ITT providers should take the lead, act as the gatekeepers to quality and stand by their decisions to fail trainees as a sign that they care about standards of teaching.”

As such, it seems that although the figure is greater than previously, there is a mix of long-standing and pandemic-specific reasons that have driven it higher than for past cohorts.

North v south: disparity in regional outcomes

Meanwhile, the DfE data also showed some notable disparities in the regional breakdown of the data about the number of trainees who passed and now have jobs.

For example, in the East of England, 92 per cent of trainees received QTS while in the South East, it was 91 per cent.

Conversely, in the North West, just 83 per cent achieved QTS and, in the North East, 84 per cent.

Furthermore, the North West and North East have the highest percentage of trainees yet to complete, at 13 and 10 per cent respectively, and the lowest numbers of trainees now working in state schools, both at 62 per cent.

This is more pronounced than the previous year’s data for 2018-19, where all regions had 90 per cent or more QTS success rates, although the highest rates were still in the South East (92 per cent) and East of England (94 per cent) compared with the North East (91 per cent) and North West (90 per cent).

However, even then, the North West and North East had the lowest take-up of teachers in secondary schools, at 69 and 68 per cent respectively.

The maps below shows the full data for each region from the past year.

So what might the reasons for these differences be?

Hollis’ supposition is that several things may be occurring here that incorporate some of the earlier issues.

“We know it’s easier to recruit in the north and there are fewer jobs, so it may be too many people are being trained in the north.”

This is not because providers are deliberately over-recruiting, though, but is rather down to a mix of the increase driven by the pandemic and wider concerns about a shortage of teachers.

However, the regional difference in where teachers are needed means this does not have the positive effect it could have, as is made clear by the lower numbers in some regions of teachers failing to take up jobs in state schools.

Hollis, though, says the regional data could be made more useful to help focus retention in the areas where it is needed most.

“One of the things we’ve been saying to the DfE for a long time is that the teacher supply model isn’t regional enough; it doesn’t tell us where the teachers are needed in the country,” she notes.

“We know teachers don’t travel - the DfE’s own research says teachers don’t migrate away from where they live and where they train. So, it’s no good training in the North East of England when the jobs are needed in Kent, or the Norfolk coast, or wherever it might be.”

Jones notes, too, that if trainees cannot find a job close to home, it can be a barrier to working in the sector.

“Teaching is tough and it’s understandable, given their workload, that trainees want to limit commute times,” he notes.

“This can be an issue and is likely to be a greater barrier in areas where public transport is less readily available.”

Concerns over the diversity of those receiving QTS

Another area of interest - and concern - comes when looking at the characteristics of trainees and those who achieve QTS.

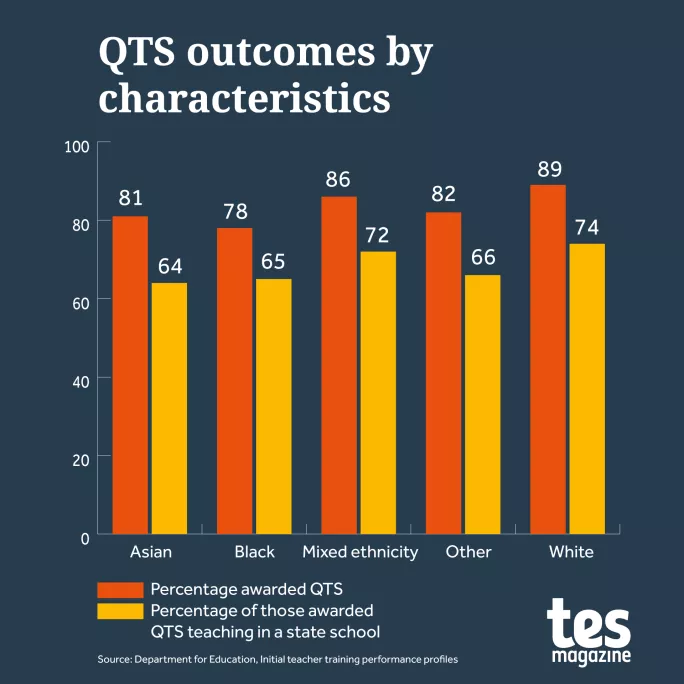

For example, 89 per cent of White trainees achieved QTS compared with 78 per cent of Black trainees.

Meanwhile, 81 per cent of Asian trainees, 86 per cent of mixed ethnic group and 82 per cent of those who fall into the “Other” ethnic category achieved QTS.

There is also a notable variation in the number of trainees by characteristic and whether they end up working for a state school once they qualify, as the table below shows.

Concerns around the number of Black, Asian and minority ethnic teachers in the school workforce were reported on in detail by Tes earlier this year, with many providers striving to improve initial recruitment and the subsequent experience on course for these trainees.

The issue was also detailed in a major recent report by the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER), titled Racial Equality in the Teacher Workforce, which highlighted these issues.

“By the time applicants have enrolled, completed their training and achieved qualified teacher status, Asian, Black, mixed and other ethnic minority groups are under-represented compared to the wider population,” the report said at the time.

Jack Worth, school workforce lead at NFER, said that the DfE data suggests these are issues within ITT and they continue to impact the rest of the sector.

“The ethnic disparities in QTS completion and entry that we identified in our recent research on racial equality are still very much evident,” he told Tes.

Hollis said the data should “shock” the sector and deserved further investigation, as it echoed similar reports that have shown acceptance rates to ITT courses is often lower for Black trainees.

“There is a real need to understand what’s happening. Because that doesn’t feel right in any way. Something is going wrong, and what is that thing that’s going wrong?” she asked.

“The honest answer is, we don’t know what it is - and we need to find out because I know those numbers should shock the sector. Something needs to change. It’s not right.”

Why are state schools missing out?

When combined, this shortfall between those who achieve QTS and those found working in state schools 16 months later throws up, perhaps, the most eye-catching figure of all: the state sector is missing out on 8,485 newly qualified teachers.

This is not a new phenomenon caused by the pandemic. For example, in 2019-2020, 26,751 trainees achieved QTS but only 19,725 were in state schools 16 months later, so 6,000 were missing from the data. The year before that was almost identical, as the table below shows.

It should be made clear that these figures are not definitive - the DfE notes that data for teachers working in state schools is provisional and revised figures are due in November 2022 as part of wider school workforce data.

These may show an increase - or maybe a decrease - but it is hardly likely to move the needle much. So, where are these 8,000 (or so) missing teachers?

Why are people completing QTS but then seemingly never entering a classroom? Where do they go?

It seems reasonable to assume some will have gone into the independent sector - something that Sredzki-Seamer says she sees from her cohorts, with around a quarter usually ending up in independent settings.

She says one reason for this can be that independent schools move faster to snap up new teachers.

“Independent schools advertise much earlier than state schools. One of ours got a job offer in an independent school last November when most of the others didn’t start having interviews until March.”

Jones also says independent schools can be attractive to new teachers owing to a raft of perceived benefits, such as “smaller classes, more narrow ability ranges, potentially fewer behavioural issues, less pressure from Ofsted”.

However, it is unlikely this huge gap is entirely due to the independent sector.

In fact, Sredzki-Seamer says part of the gap might simply be down to some trainees deciding a career in teaching is not for them and so they never enter the sector, despite achieving QTS.

“Many of our trainees also find the clash between what pedagogy says and what they are realistically able to try out in the classroom really tough,” she says.

“Schools are under pressure with the recovery curriculum and Ofsted deep dives almost pushing them to opt for formulaic approaches, with prescribed lesson plans, resources and activities, and throw creativity and teachers’ individuality out of the window.”

Jones notes that if someone achieves QTS but decides not to teach, it does not mean they may not end up a teacher eventually.

“Those who are not teaching have chosen not to because it’s not for them, they find it too difficult, or were unhappy with pay or conditions, but finished their course because having a QTS is a good thing and something they can fall back on later in life.”

Hollis meanwhile says it may also be the case that some people with QTS still go on to work in schools but in roles that are not picked up in the DfE data.

“I’ve trained people before who decided what they want to be is an educational psychologist but they feel that having QTS is a really good stepping stone towards that and being able to spend time in schools,” she says.

As such, these people may not be counted in the teacher data but are still in the system performing important roles.

Furthermore, anyone who ends up working in early years education outside of the state system will not be counted, while some may have moved to teach internationally - although that is likely to be a very small proportion of the overall number.

Put all of these reasons together and it is clear that the headline of 8,000 lost teachers is not the whole picture. And, as noted, this years figures may yet be revised and paint a more healthy picture.

Nevertheless, it shows that there remains a leaky pipeline between achieving QTS and going on to work in the classroom, which needs to be properly understood and fixed. Otherwise, the sector risks continuing to miss out on hundreds - if not thousands - of potential new recruits each year.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article