Is this the way to get teachers into rural schools?

“Loons” and “quines”. Loons and quines. Loons and quines?

Teacher Caroline McFarlane was staring back and forth at a café’s two toilet doors - and had no idea which one to open.

If you’re from the North East of Scotland, and au fait with the Doric form of the Scots language, you’d have no problem. But if you’ve barely seen Scotland beyond the Central Belt and aren’t able to pronounce “Moray” - it’s like Andy Murray’s surname, in case you’re wondering - let alone place it on a map, you might just have to take your chances when nature calls.

This was the dilemma that McFarlane, who teaches design and technology, faced back during her probation year in 2011-12: she had no idea that “loons” and “quines” was Doric for “boys” and “girls” in this part of Scotland that she’d never been to before - and which was now her home, at least for the next year.

McFarlane found herself in this pickle after becoming one of thousands of teachers to take the plunge with the “preference waiver” - a bold, ingenious and long-established piece of policy in Scotland, but one that is little heralded outside education circles.

Here’s what it proposes.

Imagine agreeing, after years of study for your chosen profession, to work absolutely anywhere in the country for your first job - to be sent where you’re most needed rather than where you’d choose to go. This will include places that take five buses to get to, or small islands where you could quite easily end up on your own for Christmas because all the ferry crossings have been cancelled.

New teachers, remote schools

Each year, hundreds of teachers at the start of their careers do exactly that in Scotland, and have done so for nearly two decades now. Some 5,827 teachers have taken the plunge and - in the lingo of student teachers across Scotland - “ticked the box”. With that simple click of a button, they give up any say over where they are placed, hence “preference waiver”.

How the preference waiver works is simple to explain. Since 2004-05, teaching students entering their probation year (when they continue their studies while being guaranteed a 0.8 full-time equivalent post in a school, or 0.7 as it was originally) can choose to tick a box that means they agree to work anywhere in Scotland. In return, on top of the standard probationer salary of £27,498 (which could rise soon if long-running teacher pay negotiations are concluded), they receive an extra preference-waiver payment, currently set at £6,000 for primary teachers and £8,000 for secondary teachers, before tax and national insurance deductions.

In recent years, more than 10 per cent of teachers entering their probation year - officially known as the induction year - have usually ticked the box. Some embrace the adventure of it all, the throwing of dice that could result in them being sent to a tiny island school - or, sometimes, to a big secondary just down the road. They may find themselves helping to plug staffing gaps and being landed with way more responsibility than if they hadn’t ticked the box - the scheme can offer an amazing opportunity to display their potential as a teacher. Some thrive so much that they never leave, putting down roots in their new home.

- Teacher shortages: Teach First to send recruits into poor rural areas

- Smaller schools: What does the future hold for small schools?

- Challenges: ‘They’re small, but don’t sell rural schools short’

But there are downsides, too. Loneliness can hit hard when you find yourself far from home, and being landed with too much responsibility may put you off teaching rather than kickstart your career. And there are rumblings of change: details are scarce, but a group quietly convened by the Scottish government is looking at potential reform of the Teacher Induction Scheme, including the preference waiver, which some local authority leaders say is overdue a revamp.

Whatever happens, the preference waiver is one of the most inventive yet underappreciated pieces of education policy since Scottish devolution in 1999. Yet its rather dull-sounding name has perhaps prevented it from piercing the consciousness of the wider public in any meaningful way, and it barely registers on Google.

Even so, it is not hyperbolic to say that it has transformed lives. For many teachers, ticking the preference-waiver box has been a true sliding doors moment, taking them to places they’d never heard of, giving them experiences and insight they’d never had before, and - in some cases - beguiling them so much that they never leave. For schools in remote areas, it has brought fresh staff and ideas, as well as freeing up existing staff and even helping to keep certain subjects alive in schools where they may have withered away otherwise.

With many of the same problems as Scotland faces - struggles to recruit new teachers into the profession, difficulty getting graduates to choose smaller, remote schools - existing elsewhere, certainly in the rest of the UK, could this be the answer that those other countries are seeking? Well, it’s first important to understand quite how well it is working in Scotland.

‘I was 287 miles and six hours’ drive from family and friends’

Emma Cooper personifies what many would see as the archetypal preference-waiver teacher: a bold young practitioner seeking opportunity and adventure, who fell in love with her new home. The history and modern studies teacher from Glasgow works at Farr High School, one of Scotland’s smallest secondaries with a roll of 87, on the north coast of Scotland.

When Tes Scotland ran a competition in the days before Christmas to find Scotland’s most scenic school - ultimately won by Lochaber High in Fort William, after 20,000 votes were cast - Cooper was perhaps more enthusiastic in her championing of her school than any other teacher in the country. She says herself that she represents the community of Bettyhill with “fierce loyalty”.

It was “so obvious” from the start that Cooper would tick the box in 2017, she says: another £8,000 to work in her chosen occupation seemed daft to turn down. And agreeing to work anywhere in Scotland did not seem a daunting prospect, having started her postgraduate teaching degree after a year in China teaching English.

Now, having never left Farr High, there is no stressful commute for Cooper - “the most I must contend with is deer and camper vans” - although the school’s catchment area for students does stretch as far as 40 miles.

“It is a much calmer experience, and I am not stressed out by the time I walk in the school gates - the Highlands truly are beautiful and special,” says Cooper, who, since taking up her post, has become engaged to an Orcadian (the Orkney Isles are a few dozen miles away, as the crow flies).

In the first couple of years after arriving at Farr High in August 2017, however, she “really struggled”. Being accustomed to living in Scotland’s biggest city and having never travelled further north than the winter-sports resort of Aviemore - a three-hour drive south from Farr High - it was “a world completely alien to me”.

“I was 287 miles and six hours’ drive from family and friends. Video calls helped but, as we have all learned from years of Zoom, it isn’t the same. I constantly felt like I was missing out on nights out or Saturday lunches. In group chats, my friends might comment about what was going on in Glasgow and frequently I would feel put out,” she says.

Cooper found it hard in school, too, where, right at the start of her career, she essentially was the history department.

“In a solo department, it really hits you when you realise, ‘I am the one responsible for this cohort’s grades’. It can be stressful, feeling like it is all down to you.”

But she also highlights the upsides of having so much responsibility and autonomy as a probationer, and of having to take students through a subject at every level.

“It gave me space to try creative projects and tailor a curriculum that worked for the students in my class and for me. In a solo department, I had the opportunity to write prelims [mocks], teach Advanced Higher, look at Insight data [an online benchmarking system in Scotland], develop department plans and more,” Cooper says.

Being a preference-waiver teacher can be a culture shock. We heard tales of a teacher suddenly finding that two-thirds of the class were missing because they were taking their family cows to the Royal Highland Show, and of a postman thinking nothing of letting himself in by the front door to leave a parcel on a table. Cooper, previously accustomed to suburban students asking what football team she supported, was now being badgered to reveal her favourite tractor (initially dumbstruck by such enquiries, she has since pledged allegiance to the Massey Ferguson). She also now knows that student attendance is likely to be down during lambing season.

But if it all sounds like a cosy Ealing comedy, the experience of a preference-waiver year can also have the bleakness of a Ken Loach kitchen-sink drama - it can feel grim up north. While Cooper may have overcome initial feelings of loneliness and isolation, not everyone does so. And local authorities such as Aberdeenshire, as we will see later, often have to contend with probationers dropping out when they find the preference waiver has not worked to their liking.

The need for the waiver scheme is driven largely by the peculiarly imbalanced physical geography and demographics of Scotland. Around 80 per cent of the population lives in what education journalist and lecturer James McEnaney recently quipped should be called “Glasburgh” - a huge conurbation comprising Glasgow, Edinburgh and the many towns and suburbs within easy reach of them. This is many Scots’ only experience of Scotland: a surprising number of people in Scotland have never been to Aberdeen, the country’s third-biggest city, let alone the wilds of the north-west Highlands.

Plugging the teaching gaps

In researching this article, I have heard about misconceptions that abound - about the Arctic extremity of weather in the North East, for example, or the frequent absence of electricity and store-cupboard staples in the Highlands. The barriers to relocating to another part of Scotland can be psychological as well as logistical.

Inverness High is one school to have benefited from the preference waiver, and the experience has largely been positive, partly thanks to the actions of the school.

The scheme “almost always” results in the arrival of “young and enthusiastic teachers who are, perhaps, slightly more adventurous and have fewer ties to their home areas”, says headteacher John Rutter.

“The knock-on effect of this is that they are normally keen to stay if we have jobs available for them at the end of their probationary year. Without the waiver, it would make recruitment even more problematic than it already is. There are very few people who put Highland in their top choices of places to spend their first year of teaching, unless they were brought up here and are looking for a return home after university,” he explains.

Inverness High staff keep a “close eye” on teachers who arrive at school through the waiver, as “the potential for feelings of homesickness and isolation is high”.

“We are lucky in having many younger members of staff already, some of whom have come through the waiver system themselves, who can mentor the newcomers from a pastoral point of view,” says Rutter. “We help them to find a place to live, if this is needed, and make sure they are involved in the social life of the school. We do encourage them to talk openly about any worries they have and help them come to terms with their move.

“It doesn’t always work and there are always some who go home at the end of their probation year - but others fall in love with the Highland way and go on to long careers in the region.”

‘There are always some who go home at the end of their probation year - but others fall in love with the Highland way’

Inverness High has seen both the ups and the downs of the scheme, then, but how common is it to have a mix: for some schools, is it all false hope and ultimate disappointment or does it genuinely provide recruitment lifelines for schools? Does the scheme have a significant impact on retention of teachers or supply to remote areas?

Surprisingly, the General Teaching Council for Scotland (GTCS), which oversees the allocation of preference-waiver teachers, says there has never been a comprehensive evaluation of the scheme.

The main evaluation we found was a 2008 report for the Scottish government by the national Teacher Employment Working Group. It noted that in the scheme’s first two years, when it was still a pilot whose long-term existence was not certain, “a significant number of teaching posts” - around 150 - were still unfilled after waiver teachers were allocated. However, that initial batch of box tickers only received £4,000 each, so this was increased to £6,000 (it remains at that level today for primary teachers, but particularly stubborn recruitment difficulties in secondary schools soon saw the payment for teachers in that sector raised to £8,000 - as recommended in the 2008 report - where it has remained to this day).

The 2008 report found that the waiver scheme had been “highly beneficial” to authorities that were not usually favoured destinations for student teachers. More than 70 per cent of soon-to-be probationers who ticked the box had been allocated across just eight local authorities - although some of those authorities will be surprising to anyone harbouring the misconception that every waiver teacher ends up in a rural idyll. The eight were: Aberdeenshire, Angus, Argyll and Bute, Dundee, Dumfries and Galloway, Fife, Highland, Moray and Scottish Borders. The three island councils of Orkney, Shetland and the Western Isles also “benefited significantly” although, given their size, the actual numbers of teachers were “very small”.

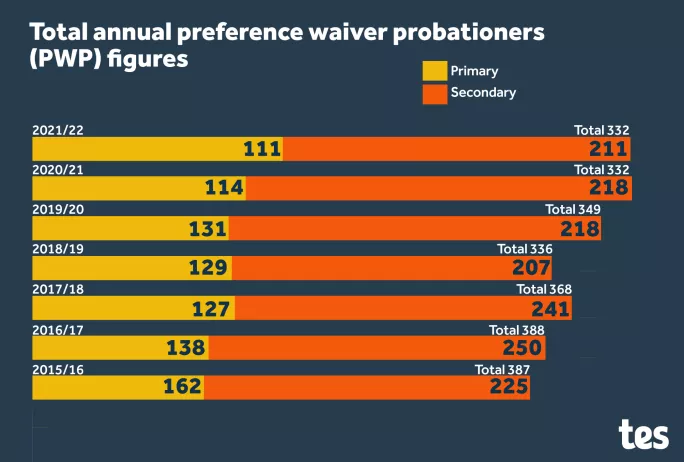

What proportion of the total graduates did these groups represent? Only 3 per cent of probationers (34 in all) ticked the box in the first year, 2004-05, although that had risen to 8 per cent by 2008-09 (281 teachers); in the past five years, the high point was 12.7 per cent, in 2017-18, and the largest number of waiver probationers in any single year was 481 in 2010-11.

Leslie Manson, as Orkney’s education director from 1998 to 2014, saw first-hand the impact of the preference waiver. Manson, who cut short his retirement to become an elected councillor and is now the authority’s deputy leader, says the scheme was “enormously helpful”.

“Recruitment for us was a real problem,” he says, casting his mind back to the days before the preference-waiver scheme appeared in 2004. Its formation not only helped in a practical sense but also on a symbolic level: Scotland’s new devolved government, only in existence since 1999, was showing that it “understood and sympathised…with the needs of the isles”. This gave education officials in Orkney “a real sense of parity”.

Previously, there were times when Orkney could not attract teachers in certain subjects for “love or money” - Manson remembers geography being particularly problematic. Students taking their crucial Higher exams were, in several subjects, frequently being taught by teachers who did not have expertise in that subject, with predictable drops in attainment. The preference-waiver scheme did not eliminate all recruitment problems “but it certainly helped on a number of occasions”.

The glut of new teachers that the waiver scheme brought to Orkney also boosted school staff who were already there, says Manson. It freed up aspiring school leaders to pursue professional development they previously could not find time for. This breathing space to try new things proved to be a “launchpad” for a number of exceptional educators.

However, there can also be downsides if a school becomes too reliant on probationer to fill vacant posts. As a number of experienced secondary teachers have pointed out to us, having a new probationer every year can result in lack of consistency - adding to the strain for principal teachers and faculty heads rather than easing it.

Caroline McFarlane - she who was flummoxed by the Doric toilet-door signs - should be a standard bearer for the waiver scheme. Having overcome the initial linguistic challenges and fears about settling in a place she couldn’t previously place on a map, she never left. More than a decade on, she remains in the North East of Scotland, now in Aberdeenshire as a faculty head facing recruitment difficulties herself.

Yet, while she extols the benefits of the waiver scheme in principle, in practice she is not currently finding that it helps all that much. She is dismayed at the lack of fellow design and technology (DT) teachers reaching her corner of Scotland. She points to about 30 unfilled DT posts in the North East, and around half a dozen schools where there is no DT department at the moment. The Northern Alliance - the regional grouping of eight local authorities covering a vast expanse of the country - received only three DT probationers in total this year, all from the University of the Highlands and Islands. Most new teachers in the subject train in Central Belt universities and do not tend to stray far from there.

In each of her five years at Banff Academy, McFarlane has had to advertise a job vacancy at least once, but on most occasions there are no applicants. Without the waiver scheme, “we would really, really struggle”, she says - which was why it was “so frustrating” not to have any waiver teachers this year. And she fears that Covid has made people even more inclined to stay close to home, after two years in which people have repeatedly been forced to stay apart from their nearest and dearest - a view backed up by GTCS figures (see the box below).

“We’ve got these amazing facilities and we just can’t staff them,” McFarlane says. The preference waiver worked wonderfully for her - she just wishes it was leading to more stories like hers.

Would it make any difference if the money was increased even further? Those who had ticked the box generally saw no shame in admitting that the money was a big motivating factor. Elaine McKay, a history teacher sent to Wick High School on the north coast of Scotland in 2015-16, bought her first car with her £8,000 (before deductions).

But all who do it say it is not the money that keeps them there (the financial incentive is only for that first probationary year, after all): it is the communities they are sent to and the challenges and inspiration they find there.

So, if money alone isn’t the answer to getting more teachers to the schools that need them, does the idea of the preference waiver itself need to be revamped?

In need of reform?

Laurence Findlay thinks so. While Findlay, Aberdeenshire Council’s education director and a former secondary head, stresses that his area has “benefited hugely from the preference waiver” over the years, concerns have emerged in recent times. In the past two years, for example, no primary teachers have arrived in Aberdeenshire through the waiver scheme.

Even some of the waiver teachers who are allocated to Aberdeenshire do not last long, if they arrive at all. For that, Findlay blames romanticism about - and ignorance of - the area. Aberdeenshire may be famed for the tourist trail of Royal Deeside, including Balmoral Castle, but also has plenty of farming and fishing towns and communities that have felt isolated from the rest of Scotland ever since the Beeching rail cuts of the 1960s.

In the past few years, says Findlay, a number of probationers have made a decision that goes against the very spirit of the preference-waiver scheme. Probationers in towns such as Laurencekirk, Portlethen and Stonehaven - to the south of Aberdeen, so closer to the Central Belt - are “quite happy” and tend to stick around, as do those in commuter towns a short drive from the big smoke of Aberdeen. Send them further north, to towns where there may be more social problems and you could be looking at a three-hour round trip to Aberdeen, however, and it is often a different story.

“They’re quite happy - but if we put them in Fraserburgh or Peterhead or Banff, they just go: ‘forget it’,” says Findlay, who has been struck by how many probationers have been unwilling to go the towns in the north of Aberdeenshire.

“I think the scheme’s got great merits, and we’ve benefited from it - but nearly 20 years on, I just wonder if it needs a bit of a review,” he adds.

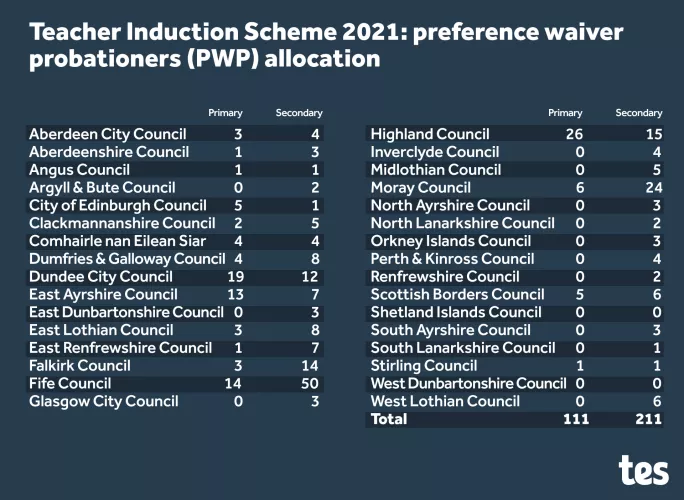

The GTCS, in allocating waiver probationer teachers around Scotland, uses an algorithm that is guided by the level of need for a certain type of teacher in schools throughout the country. It is in need of adjustment, suggest some officials in more northern local authorities who look on in dismay when bands of waiver probationers remain in the Central Belt (see the 2021-22 allocation of waiver teachers in the table below).

Findlay would like to see the waiver scheme fine-tuned to take more account of where the need is greatest, to remove anomalies where it appears that certain areas are benefiting despite not typically having the same level of long-term recruitment problems. He suggests that allocation criteria could be amended each year or every two years, in a way that might “rank the authorities so that those that really have the greatest need benefit the most”.

He also suggests that more should be done to communicate to student teachers what they are committing to when they tick the box, and to ensure that they are aware of the wide-ranging types of places they could end up in - although the GTCS says that this does largely happen already.

There is good news for the likes of Findlay, however: change may be afoot for the preference-waiver scheme.

With zero fanfare, in papers published two days before Christmas, the Scottish government recorded that it had set up a Teacher Induction Scheme Ongoing Review Group, or TISORG for short.

And one dry-sounding yet revealing bullet point revealed that the reform sought by the likes of Laurence Findlay in Aberdeenshire may be on the cards: “The operation of the preference-waiver scheme in the Teacher Induction Scheme in allocating probationers to more remote areas should be reviewed and is being considered by Teacher Induction Scheme Ongoing Review Group (TISORG).”

When we contacted the Scottish government for more details about the review and what it meant for the preference-waiver scheme, it would only say that any changes would be made in time for box-ticking teachers entering their probation year in 2023-24.

Nearly two decades since this inventive piece of education policy was thought up, the preference waiver still has legs - it looks capable of easing schools’ recruitment woes and transforming teachers’ careers for many years to come. Schools just need to ensure that new recruits are aware of local quirks in toilet signage…

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles