What has gone wrong with catch-up - and can it catch up?

It’s June 2020: England is still in lockdown number one, schools are still delivering remote learning to the majority of pupils, and the ministerial Covid press conferences are a staple of everyday life. Despite the best efforts of teachers to completely transform their way of working overnight, there are widespread concerns about how badly the educational disruption will affect the nation’s pupils. And so, the government decides to act quickly.

The Department for Education and Number 10 announce the “Covid catch-up plan” - and the prime minister calls it a “national priority”. It consists of a £1 billion package, including £350 million for a scheme known as the National Tutoring Programme (NTP) that would enable schools to access “high-quality tutoring for disadvantaged pupils at a substantially reduced cost”.

Close to 700 days later, the NTP is almost all that’s left of the grand ambition of catch-up. And yet, even the NTP is in trouble. After myriad calls for improved catch-up offers (including a reported ask of a £15 billion package from former recovery tsar Sir Kevan Collins), there is also a widely held view that there is nowhere near enough money available to schools to help students make up for lost ground.

The government’s promise of catch-up being a “national priority” appears to be broken. So what went wrong? And can it be fixed?

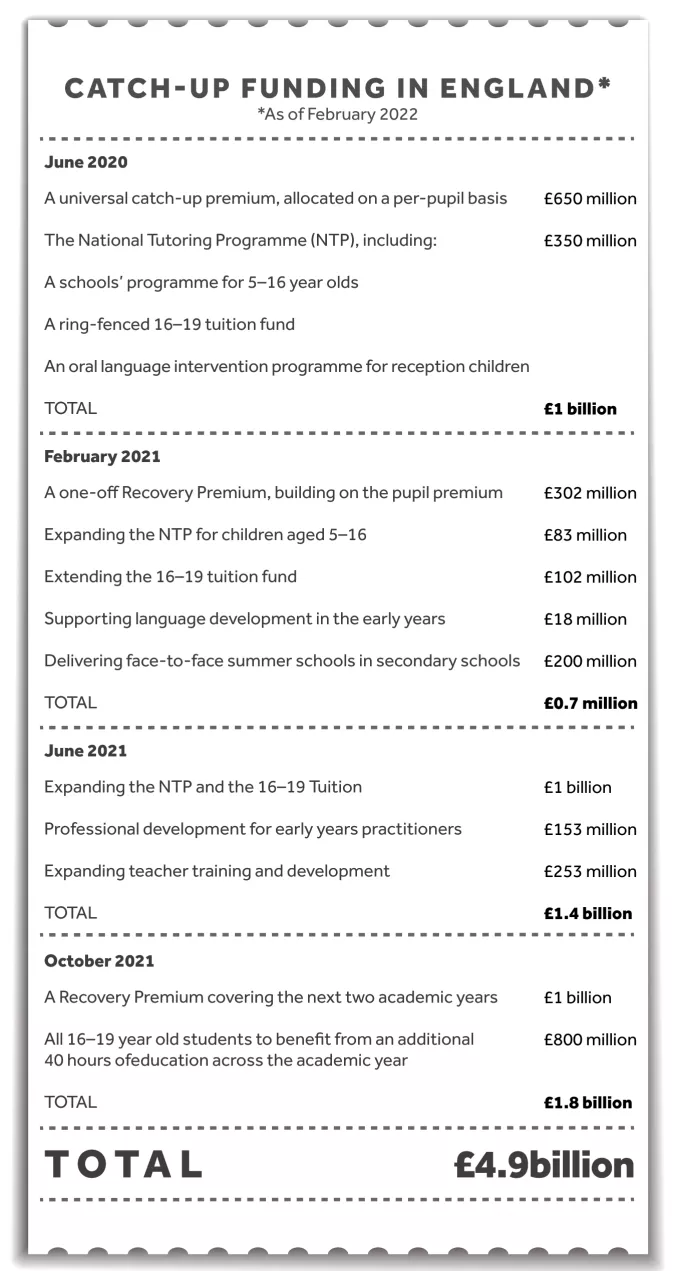

The government would argue it has spent far more than the £1 billion initially earmarked for catch-up back in 2020. The oft-quoted figure it uses is £5 billion. But exactly how this money has been spent is complicated, as cash has come through several funding streams (you can see a more comprehensive breakdown at the bottom of this article).

A total of £1 billion was first announced in June 2020, including £650 million for a catch-up premium and £350 million for the NTP, but this has been slowly added to over the past two years, including NTP expansions in February 2021 and June 2021, of £83 million and £1 billion respectively.

Criticism of the funding has been two-pronged: it’s not enough cash, and the cash that is being spent is being spent badly.

On the first, Natalie Perera, chief executive of the Education Policy Institute, says that the £5 billion “falls short of what the evidence tells us is needed for pupils’ education recovery”.

She says that the think tank’s research has shown that, based on the impact of the pandemic on outcomes, “a recovery package of around £13.5 billion is required to support pupils in England.”

She’s certainly not alone. The government’s education recovery commissioner Sir Kevan Collins infamously quit his post last year after the government refused to fund anything close to the £15 billion catch-up package he’d requested.

Numerous other studies and interested parties (including school leaders and unions) have said the same: the money doesn’t get close to helping enough, particularly with all the other financial pressures schools are under.

On the second point, criticism has been widespread about the government’s understanding of where the money is needed and how it is allowed to be used.

Earlier this year, the Commons Education Select Committee - a cross-party group of MPs - released a damning report calling the overall catch-up process a “spaghetti junction” of funding.

The report said that complications surrounding the funding were “piling more work on teachers and support staff who have needed to navigate multiple funding processes to access different streams of funding”.

Funding to support language development, money for professional development for early years practitioners, and cash for face-to-face summer schools are all initiatives that come under the umbrella of catch-up, but the committee’s report says that schools have found accessing cash to be “complex” and that funding schemes should be “simplified and merged into one pot”.

It’s a view shared by school leaders, with Geoff Barton, general secretary of the Association of School and College Leaders, saying catch-up “lacks a cohesive strategy”.

“There have been various pots of money announced at various times that have made it very fragmented,” he adds.

The trouble with the NTP

The NTP programme is the main funded pillar of catch-up, and this, in particular, has come under intense scrutiny for its confusing nature. Labour shadow schools minister Stephen Morgan says that the programme has “squandered millions of pounds of public money”, citing some of the scheme’s gaffes - such as sessions being run to empty classrooms - and the delay in fixing these issues when flagged.

Meanwhile, heads have told Tes that the confusing nature of the NTP’s different strands has deterred them from properly engaging with the scheme.

This year, there are three different strands of the NTP (see box, below), and the money to cover the sessions on each strand is provided at different levels.

Again, Barton says the funding for each strand isn’t enough, leaving schools “having to find the remainder of the cost from stretched budgets”. But even beyond the sums involved, many heads have found the navigation of the funding off-putting, especially with rapidly changing Covid rules and regulations to get their heads around, too.

Michael Tidd, a headteacher at a three-form-entry junior school in Sussex, says: “I think the different pillars and way the funding works is complicated - it’s not clear, and it’s put me off. I’m someone who regularly reads and re-reads the guidance on this from the DfE, but I’m trying to run a school at the same time as doing this, and there are a lot of other things that have been going on this past year.”

If the NTP managed to deliver the education recovery it was designed to achieve for pupils, then perhaps the problems with access and funding streams could be forgiven.

However, many school leaders feel it has let them and their students down.

“The academic mentor side of things could have been useful for my school, I think we could have benefited from that,” says Tidd. “But sorting it through a third party, the complication of it, did put me off - I’ve heard stories about [current NTP provider] Randstad from others.”

An assistant head at an all-through school in the Midlands, who asked to stay anonymous, says she feels a sense of frustration at how administrative issues have hit her pupils’ experience of the scheme.

“Without a shadow of a doubt, this scheme has made a very hard job a lot harder, for people who are trying to do right by kids,” she says.

On top of the general issues, there have been certain regions harder hit by NTP challenges, argues Chris Zarraga, director of Schools North East. Zarraga says that in the first year of the programme, in particular, schools in the area found tutoring “extremely slow and cumbersome” to set up. “The lack of pre-existing tutoring infrastructure, as well as challenges around recruitment and retention, has made it difficult for North East schools to engage with the scheme,” he explains.

The issues above have meant that many schools - around two in every five - have not used the scheme to date, despite threats of funding having to be returned if not used by the end of August.

Catch-up: not a total bust

So has catch-up been a complete failure? It would be unfair to suggest there were not some schools that have benefited from the packages.

The Nuffield Early Language Intervention (NELI), for example - designed to improve the language ability of children in Reception - has received some praise from school leaders. Simon Kidwell, headteacher at Hartford Manor Primary School in Cheshire, says this has been “really successful” for children at his school.

“Children are turning round to each other and having conversations,” He says. “Children who’ve gone through the programme [are using] full sentences rather than one or two words, and we’ve seen a big improvement in storytelling language as well.”

Over two-thirds of primaries have signed up to the £18 million scheme, which launched in 2020 and is run over 20 weeks by a specially trained teaching assistant.

It’s also undeniable that there has been some joy with the flagship catch-up programme - the NTP - as well, though much of this has been at schools that have primarily engaged with the school-led element of the programme. This does technically fall under the banner of the NTP, but - as the name suggests - involves the schools co-ordinating the tutoring themselves.

Indeed, Zarraga says this has been a blessing, and that the addition of it to the programme has “ensured greater flexibility”.

He adds: “While schools do still face difficulties in accessing the tutors they need, with a complex system to navigate and significant additional workload pressures for teachers and admin teams, the efforts are paying off. Where schools have engaged students it has been an effective tool.”

Chris Dyson, headteacher at Parklands Primary School in Leeds, has also used the school-led tutoring element of the programme and says it has “massively helped” pupils.

“It’s been great for us, and I can’t speak highly enough of the tutors we’ve had,” he says.

Although Dyson’s school has used this strand of the scheme, staff have used it to book tutors from The Tutor Trust - a charity provider that also provides tuition through the NTP’s Tuition Partners strand.

Asked if he would recommend other heads get involved with the NTP, Dyson says: “100 per cent - I’m surprised more schools haven’t.”

The real impact of Covid on learning

While there has been some success in catch-up, it is clearly nowhere near what is required - especially considering recent damning reports that reveal the extent of the pandemic’s impact on children’s education.

Take the Education Endowment Foundation’s finding that three extra early years children per class are not reaching the expected development standards for their age group, for example. Or the National Foundation for Educational Research’s recent study, which concludes that catch-up plans should give equal focus to emotional support amid reports that schools are experiencing an increase in pupils with mental health issues.

The EPI’s Natalie Perera acknowledges that the recovery package as a whole prioritised some “important and evidence-based priorities, including extra funding for tuition, teacher development and early years language support”. But she adds that the package overall “is still unlikely to address the loss in learning caused by the pandemic, let alone start to close the widening gap between disadvantaged pupils and their peers.”

She adds: “It is neither large enough nor does it adequately target funding and support to the pupils who need it the most.”

To give some international context, the EPI has previously published research comparing England’s spend on catch-up with other countries. It found that spending on education catch-up represented about £2,100 per pupil in the Netherlands - around seven times larger than the plans for England.

Even within the UK, there has been variation in spending. Previous research has found Scotland has spent more than England on catch-up, although the nature of this has been vastly different. There has been no equivalent to the NTP, with much of the money going on general spending, such as employing more teachers and organising summer activities.

Indeed, John Swinney, Scotland’s former education secretary, even said he was “nervous about the concept of education catch-up” when asked at a committee meeting in the Scottish Parliament last year.

So how much damage has the perceived low level of funding and the issues with the scheme in England done - and over two years on from the first school closures, can they be rectified?

Answering what position we’d be in if catch-up had been funded to a higher level is somewhat difficult, given it’s a counterfactual situation, but the consensus is that children would be in a lot better position than they are.

Barton says that the “unfathomable” way catch-up - and particularly the NTP - has been run, has “undoubtedly” reduced its effectiveness.

James Bowen, director of policy at the NAHT school leaders’ union, says the scheme so far has been a “massive missed opportunity”, adding: “Had the government been prepared to back its own recovery tsar, we could have had such a more ambitious programme to support schools rather than the partially funded schemes, many of which have failed to properly get off the ground.”

If assessing how much better things could have been with a better programme is difficult, assessing why more resource and money was not put into it is even harder, given that everyone - including the government itself - was at pains to recognise its importance.

Barton says his best guess is that instead of allowing educators to do what is best for children, the DfE has been driven by the desire to have evidence trails “at all stages to demonstrate to the Treasury what the money has been spent on”.

He sums this up by saying that bureaucracy has “trumped common sense”.

Bowen reaches an even simpler conclusion, saying it “just boils down to the Treasury being unwilling to spend the money”.

Where next for catch-up in England?

So what direction should the scheme be taken in now to help catch-up to catch up?

The DfE has previously said its “ambitious recovery plan” has “consistently targeted recovery funding where evidence tells us it will be most effective” - it says this is tutoring, teaching and “direct funding targeted at those that need it most”.

It added that its support is “especially focused on helping the most disadvantaged and vulnerable [students] and those with the least time left in education, wherever they live”.

Others have advocated different approaches. For example, Perera says that an increase to the Early Years Pupil Premium, before- and after-school clubs to support learning and wellbeing, and targeted funding for disadvantaged 16- to 19-year-olds “would help to limit learning losses and improve equity”. However, she says that, to date, these have “not been supported by the government”.

Similar changes have been called for by Labour. Shadow schools minister Stephen Morgan has asked for a plan including not only effective tutoring but also new before- and after-school clubs, a focus on mental health and further targeted learning support.

Looking at the NTP specifically, education leaders have detailed thoughts about what is needed to make the flagship scheme a success.

In the next academic year, one change that many have been calling for with the scheme will be realised. Back in March, the DfE revealed that catch-up tutor cash would go to schools directly in 2022-23, instead of via the three different strands.

Tidd says the move to school-led tutoring will help iron out some of the administrative issues staff have experienced, while John Nichols, president of The Tutoring Association (TTA), says it is a “welcome step” and shows that the “DfE are listening to schools and experts”.

“I think the catch-up scheme can catch up,” he adds.

Julie McCulloch, ASCL’s director of policy, believes the scheme can work if schools are given the autonomy they need.

“Schools need to be trusted by the DfE and given the freedom they need to make tutoring work for their pupils,” she says. “The NTP has the capacity to make a difference for thousands of pupils if the government can resist the urge to meddle.” However, recently announced plans to produce league tables of schools and their tutoring engagement may scupper hopes of this.

Becky Francis, CEO of the Education Endowment Foundation - which was part of a group that ran the scheme in its first year - says that the way the scheme is communicated and accessed is key.

“Teachers face a huge array of complex and different priorities at any given time,” she says. “So making the programme as simple and easy to navigate will help ensure that the NTP helps rather than hinders.”

These words will resonate with heads, who last month slammed “ridiculous” plans for the government to claw back cash for this academic year that remains unspent by the end of August, despite training for non-teachers to deliver the tutoring not being available until two months into the academic year, and schools receiving a huge lump sum of cash less than three months before the school holidays.

So can catch-up catch up, or should it be consigned to failure? Writing it off just two years into a several-year strategy seems harsh, but of course, as McCulloch points out, for some students - those who have finished A levels and are moving out of school education - any future improvements or changes will come too late.

For many, catch-up has been a missed opportunity, and it remains to be seen whether those opportunities can be re-harnessed in the coming years.

The question that comes up repeatedly when you mention the NTP and catch-up to educators is whether it can win the “hearts and minds” of those on the frontline - teachers. After two years of problems, it’s almost a pariah scheme to many. Whether it can catch up depends on whether it can turn this conception around.

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

topics in this article