What will the pay rise mean for teachers in real terms?

Teachers will receive a pay rise of 5.5 per cent for 2024-25, across all grades, the Department for Education confirmed this week.

It means that, from September, the starting salary for newly qualified teachers in England (excluding London, where rates are higher) will be £31,650, up from £30,000 in 2023-24.

The pay announcement was welcomed by the sector. But where do the new rates sit in the context of new-teacher pay over the past couple of decades?

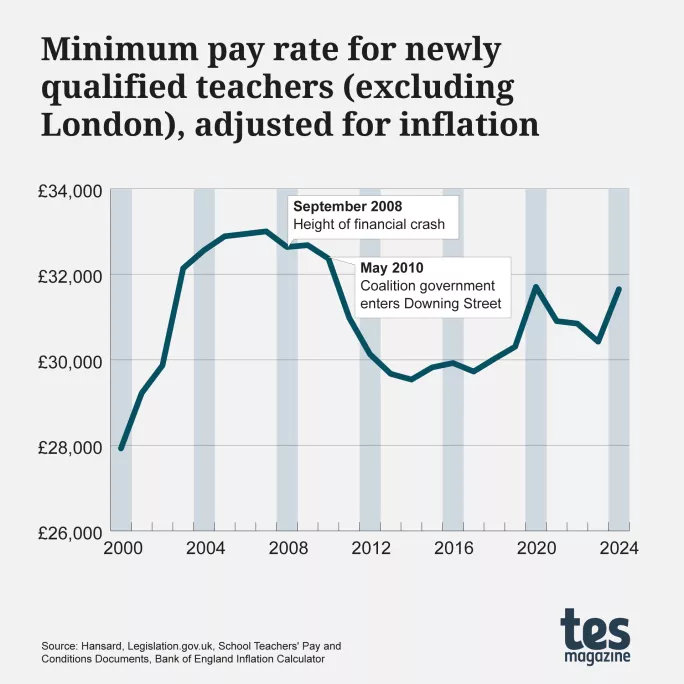

By comparing minimum starting salaries for newly qualified teachers in England between 2000 and 2024, and adjusting these rates for inflation, Tes analysis shows the context of the latest rise in real terms.

As shown by the graph above, the 2024-25 starting salary is a real-terms increase on the previous three years. The 5.5 per cent rise is above inflation, which was at 2 per cent in the year to July 2024.

So, unlike previous pay rises - such as in 2022 and 2023, when teachers experienced real-terms pay cuts - this one really is a boost.

But in real terms, the September pay rate for newly qualified teachers is actually below the 2020 level, when new teachers started on the equivalent of £31,705 today (then the salary was £25,714).

How teacher pay has changed in reality

Looking further back, the 2024-25 rate is below, when inflation is taken into account, salaries between 2003 and 2010, when for eight years the entry salary was above £32,000 in today’s money, reaching a high of £33,003 (in 2024 terms) in 2007.

This means that a new teacher’s purchasing power was higher in 2003 than it is today.

As the graph shows, real-terms new teacher salaries were already falling before the 2008 financial crash, and the decline in pay accelerated once the coalition government took office in 2010. New teacher pay was frozen in 2011 and 2012 under austerity measures.

When newly qualified teachers did receive a pay rise in 2013 (in cash terms, starting salaries increased from £21,588 to £21,804) even that meant a real-terms cut. The lowest real-terms entry-level salary since 2001 was in 2014, when new teachers earned £29,538 in today’s money.

- Teacher pay scales 2024-25: what will your salary look like?

- Pepe Di’Iasio: Why now is the time for teacher pay parity

- Teacher appraisals update: what you need to know

The previous government pledged a starting salary of £30,000 to aid teacher recruitment in 2019. But by the time it was introduced in 2023, the cost-of-living crisis and rising inflation had eroded its competitiveness, and it did not improve take-up for initial teacher training.

It is worth noting that the picture is more varied for different types of new teachers. In 2018 the government introduced early-career payments to boost recruitment of teachers of maths, physics, chemistry and languages, where there are shortages, and this was later shown to have improved recruitment.

Christine Farquharson, associate director at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, referring to the average pay of all teachers, says: “Average teacher pay is no higher in real terms today than it was in 2001-02. By contrast, the average worker in the economy has seen a real-terms pay rise of 18 per cent over this period.”

By comparison, the annual median real salary for graduates in England decreased by 13.3 per cent between 2007 and 2023, according to the earliest available official data.

In addition, Farquharson points out that since 2010 teacher salaries at the bottom end of the pay scale have been better protected than those at the top.

So while Tes has taken entry-level pay as a benchmark for a year-on-year comparison, the real-terms losses for mid- and senior-level teachers are worse. This is detailed in the 2024 report of the School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB), which shows that the real-terms change in median gross earnings for all teachers was a drop of 18 per cent compared with 2010.

Comparisons with the wider economy

As well as looking at the numbers in real terms, teacher pay should be considered within the context of the wider earning economy, Farquharson suggests.

“A 5.5 per cent pay rise next year will match private sector earnings growth, preventing teachers from falling further behind,” she says. “But pressures on recruitment and retention will remain.”

Jack Worth, lead economist at the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER), agrees. The pay rise “is a good first step”, he tells Tes. “But it’s only a first step because over the last decade and a half teachers’ pay has deteriorated.”

NFER research shows that in 2010-11 teachers’ starting salaries were at the 37th percentile of earnings for all full-time workers in England (including those outside the teaching profession), meaning that 37 per cent of full-time workers earned less.

But by 2022-23 teachers’ starting salaries had fallen to the 29th percentile.

The STRB puts this data into more specific context, measuring new teachers against comparable roles in other sectors (as opposed to all full-time workers). Here the minimum starting salary for teachers is between the lower quartile and median.

Worth says that while the deterioration of teacher pay in real terms has “reduced the purchasing power of teachers”, at the same time “average earnings have grown much faster in the wider economy, which makes teaching less competitive”.

In real terms and in comparison with the wider economy, a 5.5 per cent increase in teacher starting salaries may not be enough to boost recruitment.

Ellen Peirson-Hagger is senior writer at Tes

For the latest education news and analysis delivered directly to your inbox every weekday morning, sign up to the Tes Daily newsletter

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

topics in this article