Why teachers need to debate Big Tech in the classroom

“Think about a computer that gives you enormously personal, helpful advice. What should I do today? What am I interested in? Where should I go? How should I make these decisions?…We’re on the cusp of an acceleration of the level of impact of that, and it’s almost overwhelming good.”

This quote is from Eric Schmidt, former chairman of Google. What I think is important about this quote is the vision it projects of human wellbeing. It seems, according to Eric, that the more of our lives we hand over to Google, the happier we will be.

And it’s hard not to think that Facebook, Apple and Amazon and more share this vision.

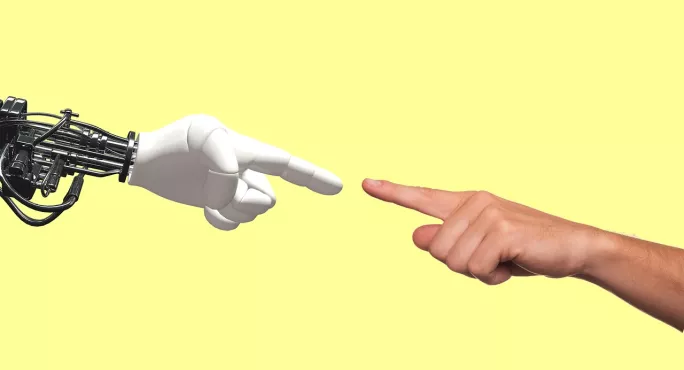

Are Big Tech and AI a risk to humanity?

It’s a vision I find troubling and one that, as teachers who are responsible for the social and personal health of our pupils, we need to talk about - for two reasons.

The first of which is the importance of competence.

Developmental psychologist Erik Erikson developed a framework of psychosocial development way back in the 1950s and 60s that is still seen as highly instructive. Through the school years, successful navigation of these stages involves the child developing a sense of autonomy, initiative and industry.

All of these things point to the need for the child to gradually take charge of their life by trying things out, learning from mistakes, discovering new skills, making a tangible impact on their expanding world - becoming competent.

Take that idea and match it with Eric Schmidt’s vision, where Big Tech will take control. In fact, why look into the future? What about predictive text, where your phone will tell you what you’re going to say? Or Netflix, which will show you what to watch next? Or Google Maps, which will tell you how to get where you’re going?

Convenient - but at what cost?

These things are really convenient. But they’re convenient in the same way that many students like to be spoon-fed information without having to think or really understand what’s being taught. In other words, convenient can sometimes be harmful.

This convenience in technology is irrefutable and almost irresistible, but I have had constructive conversations with students about the disingenuous way in which these conveniences are “sold” to them.

Teenagers, especially, are finely attuned to respect, and to disrespect. An excellent way of talking to them about the downsides of technology is to ask whether tech companies are treating them with respect, when the companies appear to give them things for free and yet manage to make so much money. Where is that money coming from? What product are they selling to get it?

Sharing the wealth?

You can even make it personal and appeal to their sense of injustice. For example, in a world that’s so focused on fighting inequality, how does Jeff Bezos get so little criticism as he heads towards being the world’s first trillionaire?

With these kinds of conversations, it doesn’t take long for students to feel more sceptical about the real intentions behind the technology they’re being given. That isn’t going to stop them using it, but it might make them take a more balanced view about how and when they do.

The second reason why I think it’s important to discuss this in schools has to do with risk.

Whether we like it or not, risk is a key building block of young people’s development. Young people need to test boundaries to work out and expand their world in order to live fully.

Taking decisions away from us, correcting mistakes before we make them, encouraging us to live ever more virtually - all of these things take away the kind of expansive risk-taking that is so vital to young people.

Here is where sports, arts, trips, clubs, challenges of almost any non-virtual kind come into their own. And sometimes school is going to be the only place where a child is going to have a chance at this.

Shouting against the crowd

But it’s hard to argue against the Big Tech vision.

These companies have two powerful weapons. First, it’s the, ”What are you clinging to the past for?” argument. This is especially hard to deal with as a teacher because you are always the older person in a room full of younger ones. ‘The young people get it - just get out of the way.”

But, no, the young people don’t get it, at least not all of it. They don’t usually know that Google, whilst pretending that all it wants is to make life more exciting and fun, is actually just grabbing, packaging and selling our attention to advertisers. Young people need to know that they are not Google’s customers - they’re the product.

Another weapon used to shut down dissenters is inevitability: ”This is going to happen whether you like it or not, so you may as well get on board or be left behind.”

Again, no - it’s not inevitable. They need all of us to make their vision of the future happen. And their future is actually about making money for themselves. It’s really important not to forget that.

A debate we must have

Maybe you think these concerns are over-the-top. There are so many great things about technology, we can take a few downsides.

To that I would say, what I’m talking about here is a direction of travel. It’s not about what technology has or has not done so far, it’s about where Big Tech wants to take us, and the impact that may have on our young people.

And to ensure that we can have that debate, we need to make sure that young people are aware of what is going on, recognise the downsides of this huge push to automation, big data and artificial intelligence and have enough of their own human intelligence to walk away from it.

Aidan Harvey-Craig is a psychology teacher and student counsellor at an international school in Malawi. His book, 18 Wellbeing Hacks for Students: using psychology’s secrets to survive and thrive, is out now. He tweets @psychologyhack

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article