Primary testing and SEND: the ghost pupils in our system

When the results from the new multiplication tables check (MTC), taken by 625,688 Year 4 children in September, were published for the first time in November, the headline statistic was encouraging for the government: 25/25 was the most common score, achieved by 27 per cent of pupils.

What’s more, for children who are classed as receiving special educational needs (SEN) support, a full score was also the most common outcome - with 11 per cent securing this mark. And for pupils with an education, health and care plan (EHCP), top marks were the second most common outcome - with 6 per cent achieving this score.

At last, statutory assessment that is truly inclusive?

Unfortunately not. The more eye-catching stat is actually how many pupils with SEND and those with EHCPs did not take the test - 17 per cent and 54 per cent respectively. That equates to 26,692 children not sitting a test that the Department for Education claims will “determine whether pupils can recall their times tables fluently, which is essential for future success in mathematics” and also “help schools to identify pupils who have not yet mastered their times tables, so that additional support can be provided”.

So, what’s going on?

DfE data shows that the most common reason given for pupils with EHCPs not sitting the assessment was them working below the national curriculum standard (39 per cent), while other reasons included being unable to participate, having only just arrived at their school or simply being absent.

However, a further 3,000 pupils did not take the test with no reason given at all.

Conversely, though, when we look at data for children not receiving SEN support and those without an EHCP, just 1 per cent did not sit the test.

For Alex Grady, head of education and whole-school special educational needs and disability (SEND) at the National Association of Special Educational Needs (Nasen), the lack of participation in the MTC is sadly not a surprise.

“It isn’t particularly inclusive,” she says. “The tests are not a particularly helpful or successful way of finding out what this group of children is actually able to do.”

Can we make primary assessment more inclusive?

Laura Slinn, executive headteacher of two SEND primary schools in the academy trust Endeavour MAT, agrees. She says some features of the test make it “really challenging” for their pupils.

“Even with the adaptations you can make for the MTC, the processing time is still not long enough for our pupils with SEN,” she says. “If we were allowed to give them the amount of time recommended in their individualised plans, our children would score more highly.”

In the administration guidance for the MTC issued to schools, the instructions on page 8 make it clear that it is the headteacher’s decision if a child is not entered for the test, but that they “must” record a reason.

In addition to the reasons given above, a head can make this decision if the pupil is unable to take the test even with adjustments made according to the access arrangements.

By not giving a reason for a pupil’s non-participation, schools are failing to record and therefore risk a malpractice investigation by the Standards and Testing Agency.

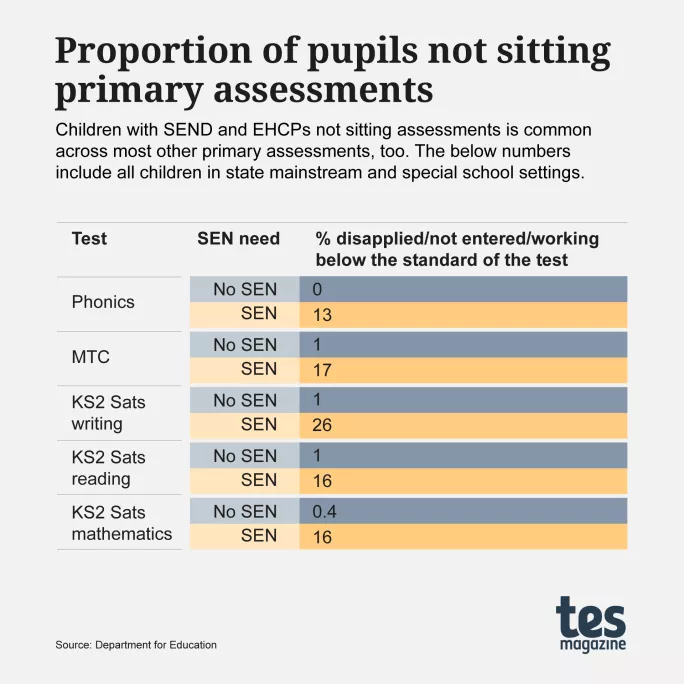

Children with SEND and those with EHCPs not sitting tests is common across most other primary assessments, too (see the table below):

Should it be expected that these proportions of pupils with SEND should not sit standard assessments in mainstream schools?

Grady says that not every child will take every test. “The fact that some children with SEND don’t take the tests is exactly what you would expect - for example, some of those with significant cognitive needs and complex learning difficulties,” she explains.

However, she argues that high non-participation in assessment only serves to limit pupils with SEND: “The problem is the assessments are not designed to show what all children can do and instead they’re a ‘hurdle’ to show what some can do and what some can’t.”

Considering this in terms of the central data, these children are essentially ghosts in the system. This is a problem for tracking progress and making schools accountable, but it is also a failure to acknowledge the impact that schools are having on children who do not sit the standardised tests.

Debbie Nice is a Sendco at St Gregory’s Church of England School in Suffolk, which delivers an alternative curriculum in a separate specialist unit for its pupils with high levels of SEND. This curriculum is predominantly focused on safety and social skills.

“The best progress can’t necessarily be expressed on paper,” she explains. “The milestones [our pupils] are hitting are often intangible and highly individualised.”

Not only that, but Nice also points out that for many of these children, the idea of tracking performance can be very complex, as what happens on a Monday can’t be reliably replicated on a Tuesday.

“For children in our unit, their performance can be really varied from day to day, so it’s much harder to measure progress,” she explains.

‘The best progress can’t necessarily be expressed on paper’

So, do we need standardised tests to be more inclusive and to incorporate some of these elements, or do we need to change them to be more broadly accessible? Or do we need a separate set of assessments for those who are not accessing the national curriculum?

Some argue that the statutory tests we have are as inclusive as they can be. Liz Twist is head of assessment research at the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) and an expert in primary assessments. She was involved in the development of the key stage 2 English tests and the development of non-statutory tests used nationally in KS2 and KS3, and claims all tests are already designed to be as accessible as possible for all children.

“The principle of ‘universal design’ is used to design tests,” she explains. “That’s why we have access arrangements such as enlarging text, extra time and the option to add breaks.”

For her, the ability to make these adaptations means that all children who are able to access the national curriculum can have a fair chance on the test.

“The fact that we can eliminate the irrelevant factors that may affect performance means that we can level the playing field,” she says. “The assessment focuses on the construct it is designed to assess (such as reading or maths). This is why it is permissible to have a reader for a maths test but not a reading test.”

Twist argues that the number of children not sitting the tests, therefore, is an indication of the number of children who are not accessing the national curriculum, as well as those for whom access arrangements were not possible, and this could be for a variety of reasons, including inadequate space or insufficient staffing.

Cathie Paine, the CEO of REAch2 Academy Trust, which is the largest primary-only academy trust in the country with 60 primary schools, believes access arrangements will not mitigate the challenges for many children with SEND and that the number of these children is rising.

“If access arrangements are understood and used to fully support a child, then some pupils with SEND are able to access the tests, but, of course, access arrangements may not support the full spectrum of need,” she says. “There are children with persistent or complex difficulties where, even with access arrangements, it’s very difficult to see how it can be a level playing field for every child with additional needs.”

Paine says the situation for these pupils is worsening because with more content in the national curriculum that they have to learn, the subsequent assessments “become more challenging for pupils with SEND than had previously been the case”.

Grady agrees, and says this is affecting some pupils with less challenging needs, who are being left disillusioned when they sit the assessments.

“The experience of the statutory tests for children who have a low level of SEN may have a greater negative impact as they’re more aware of what they can’t do, and are consequently demotivated,” she says.

So, do we need a new set of tests for those who are not accessing the curriculum, so that the progress these children are making is acknowledged in accountability frameworks?

An alternative approach to testing

There is actually evidence that a different type of assessment for all could be more inclusive: adaptive assessments.

This assessment model is already being used in the recently introduced Reception baseline assessment. This assessment generates questions in response to answers already given, so the level of challenge adjusts to the child’s current performance.

So, for example, you start with everyone taking the same set of questions, and those who answer them all correctly will then be asked a harder set of questions. Those who get some wrong will get five easier questions, and the process continues, filtering each student through a “pathway” of questions that should match their level - and then stopping once enough questions have been answered to ascertain the attainment level of the student.

This should mean the test is much more inclusive - and useful.

Given what senior primary school leaders in both the mainstream and specialist SEND sectors have said about their experience of this new assessment, this might be a preferable way forward.

“Anything like the RBA that allows visual and aural responses is more suitable for children with SEND,” says Nice.

Olamide Ola-Said, who oversaw the RBA rollout when working as a headteacher in a London primary school with an above-average percentage of children with SEND, is also positive about the RBA as an assessment system due to the more inclusive role of the teacher.

“The RBA needs to be carried out with one-to-one supervision, and the child is guided through the test,” he explains. “Therefore, it will always be more inclusive than a paper test, such as the KS1 Sats.”

‘Computer adaptive testing will enable a much more targeted assessment of students’

Grady is also a fan, noting that it is “more inclusive as it looks at what children can do” and that it also has “the potential to possibly identify needs earlier”.

Furthermore, she says that this assessment model has other benefits over a paper test, because “a test that is responsive and is designed to present questions of a difficulty that provides realistic challenge to the pupil is preferable to a paper-based test that poses many questions they can’t answer”.

The number of questions that children with SEND are asked is important, adds Slinn.

“In any standardised test used in school, the guidance will instruct the teacher to stop the test after a set number of incorrect answers,” she explains. “But this isn’t the same in the government tests.”

However, because the RBA does do this, she says it’s not only a better test of pupils’ abilities but also a “less damaging experience for the child - for their self-esteem and their self-perception [of their abilities]”.

Although it’s still early days for the RBA after its rollout in September 2021, figures suggest take-up has been very good, with only 0.99 per cent of all pupils being disapplied.

That said, some special school heads have told Tes that none of their pupils has sat the test. And it’s clear the test has not been universally well received. Ola-Said and Nice share concerns expressed across the sector about the timing of the test and the age of the children taking it.

Despite these concerns, the idea of adaptive testing clearly has some promise as a basis for more inclusive standardised assessment. Twist believes adaptive testing could definitely be used more widely to help tackle some of the issues that tests can pose for pupils receiving SEN support.

“In the future, computer adaptive testing will enable a much more targeted assessment of students,” she says.

“With a good algorithm and enough questions in your ‘pool of items’, it would be a much shorter and more targeted assessment, and students would see more items (or questions) at their ability level.”

The algorithm matters, says Twist, in order to allow trust in the test. Without it, she says, learners could end up being cut short before demonstrating their full range of ability.

Education think tank EDSK agrees, having suggested the introduction of adaptive testing as a key way of reforming primary assessments in a paper entitled Making Progress: the future of assessment and accountability in primary schools, published last year.

“From 2026, assessments for reading, numeracy and spelling, punctuation and grammar (SPG) should be delivered through online adaptive tests,” it says.

EDSK founder Tom Richmond says he believes such an approach is needed because the current system is “very piecemeal” for pupils, and the assessments need to be redesigned.

“One of the weaknesses that our reports picked up on was the one-size-fits-all nature of the current assessments,” he tells Tes.

“The computer assessments in the RBA are exciting and if we used the same technology to create a new assessment system, we can reduce teacher workload as well as generating important information.”

Richmond says there would be an “enormous benefit” for all pupils but “particularly those with additional learning needs”.

“Students with SEND would benefit from shorter and lower-stakes assessments and the move to a more logical, sequential set of tests spread over the course of their primary education,” he says.

“This would put an end to the current scattered approach that pulls a teacher’s focus in too many directions, depending on which year group they happen to be teaching.”

Richmond points out that this system has already been adopted in other countries, such as Australia and Finland - and closer to home in Wales and Scotland.

“We don’t have to look far for a solution,” he says.

Computer adaptive testing was introduced in Wales and Scotland in 2018 when changes to their curricula meant a new progression monitoring model needed to be introduced.

In both countries, the tests occur three times during a child’s time at primary school, and computer adaptive testing is used to assess reading, writing and numeracy.

So, how has adaptive testing worked when rolled out across a whole country? As you might expect, there have been benefits and drawbacks.

For example, a review of the first year of adaptive testing for Scottish National Standardised Assessments (SNSAs), based on feedback from 460 teachers, noted that moving to computer-based tests meant that in some cases “children need[ed] additional adult support to take part in the assessments”.

However, by removing limits on how long children had to take the test, and introducing audio versions of the questions and the chance to take breaks during the test, the consensus was that for pupils with SEND, the new version of testing was an improvement.

“Feedback is clear that the SNSAs are an improvement on the existing standardised assessments for children with additional support needs [the Scottish equivalent of SEND], and the accessibility features are really valued by the teachers and children,” the report said.

‘Students with SEND would benefit from shorter and lower-stakes assessments’

Headteacher James Cook echoes these sentiments: “In our school we have had positive engagement with all of our children, including those with additional support needs, accessing the [assessments],” he says.

In Wales, meanwhile, Eithne Hughes, director of the Association of School and College Leaders Cymru, says that the rollout of adaptative assessments is “generally regarded as a positive step forward”.

She says she is not aware of “any formal national evaluation of these assessments” but adds that it would be “useful in providing evidence about their impact”.

Teachers, too, may welcome this, with one primary head in Wales, Owen Clarke, telling Tes he is yet to be convinced that the new style of assessment is as “clever” as it needs to be.

“Depending on how the children answer the first few questions, it can lead to the next questions being either way too easy or way too hard. Whereas on an old-fashioned paper, it didn’t really change the rest of the test if you got the first one or two wrong or right,” he says.

What’s more - and perhaps more crucially - he says that the tests can actually be harder for some children with SEND, as they involve using a computer.

“Some of our children with learning difficulties already struggle with using computers, and therefore the test is harder as it favours children who are computer literate,” he points out.

Although adaptations have been made to allow these children to jot things down on paper, this then “impacts on time taken to do the test and also space needed for the test”, Clarke adds.

Is change on the horizon?

So, given these examples and the problem of ghost pupils in the accountability system that we have currently, is the DfE looking at expanding adaptive assessment beyond the RBA? It doesn’t appear so.

“Primary assessments are intended to assess pupils’ abilities in a fair and comparable way,” says a DfE spokesperson. “Tests and checks are designed and developed with the input of SEND experts and, additionally, modified materials and access arrangements are available to support pupils.”

The DfE doesn’t see a problem with the current numbers of pupils with SEND not taking part, saying the “overwhelming majority of pupils manage to complete these assessments, including those with SEND”.

The story behind these numbers seems to be one we hear too often in education: prioritising easy data over effective assessment.

It’s clear the potential exists for creating more sophisticated assessments, but a move to a new system would mean we will lose the ability to track standards over time. The desire to maintain that comes at the cost of all of those pupils who are unable to access current assessments.

This is a problem that isn’t going away. Instead, it will grow with the increasing number of children presenting with SEND in schools. Until it is addressed, those learners will be unable to fully engage with our current standardised assessment system.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article