Exams 2023: Results loom but is a return to 2019 standards fair?

As GCSE and A-level exam results days loom, it’s worth reflecting on the journey these cohorts have faced to reach the big day over the past four years.

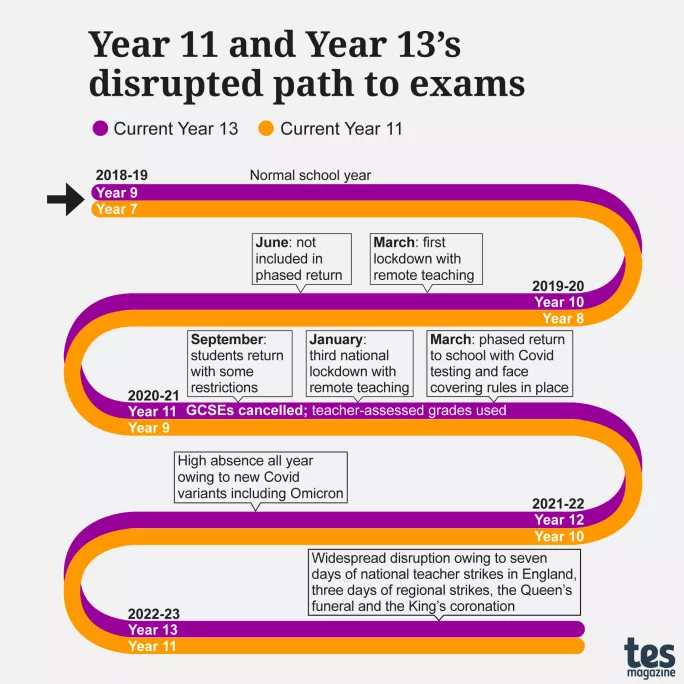

Rewind the clock to the start of March 2020 and this year’s GCSE students were young Year 8s, with just one full year of school under their belts. Meanwhile, this year’s A-level students were in Year 10, preparing for the onset of GCSEs and all that entails - including vital exam-hall experience.

Then the pandemic hit and they experienced three years of unprecedented disruption to their education - national lockdowns and remote teaching, bubbles, social distancing, rotas, bubbles and the loss of many of the usual social aspects of school that are vital to a rounded education.

- 2023 results: Attainment gap widens after GCSE grading reset

- GCSEs and A levels 2023: How will grading be different this year?

- Exam process: How 9 million exams are prepared for marking

This year, they also missed out on as many as nine days of school owing to industrial action and an extra bank holiday for both the Queen’s funeral and the coronation of King Charles.

Yet these students are the ones who face their exam grades being returned to the 2019 standard as part of the Department for Education’s desire to reduce the grade inflation that occurred because of centre-assessed grades (CAGs) in 2020 and teacher-assessed grades (TAGs) in 2021.

With predictions saying almost 100,000 fewer A and A* grades are expected to be awarded at A level, it’s no wonder some have dubbed these students the “unluckiest” of the post-pandemic generations.

Hoping for the best

Dame Alison Peacock, chief executive officer of the Chartered College of Teaching, says the situation certainly feels as if many people are simply hoping for the best in spite of all that has happened.

“In terms of exam preparation and hoping for results that are equitable and fair, I feel as though people are crossing their fingers and wanting the best for their students,” she tells Tes.

She adds that while teachers have worked hard to provide the best education possible, there is no question of the impact of the pandemic on students’ learning: “Everybody wants the world to get back to normal but the reality is it isn’t normal - children haven’t had normal experiences.”

Rob McDonough, CEO of the East Midlands Education Trust, is also worried by the narrative that exam results are back to normal this year. “Certainly the approach is [that this year] is normal because grade boundaries are returned, [but] we’re a long way from what I recognise as normal from 2019,” he says.

Indeed, as recent Tes analysis has shown, areas such as absence and behaviour are clearly suffering from a long-tail effect of the pandemic - something that makes Evelyn Forde, president of the Association of School and College Leaders, worried about exam outcomes.

“We are far from normal…[but ] with the grading going back to normal I am anxious because of all those factors that might impact the outcomes for young people,” she says.

Discussing these concerns on Radio 4 last week, Dr Jo Saxton, Ofqual’s chief regulator, said that senior examiners have been “instructed to bear in mind the context of this exam series [and] the disruptions students have suffered” in an effort to ensure results are deemed fair for all students.

‘Uncertainties at every level’

While this may help to one degree, Pepe Di’Iasio, headteacher at Wales High School in Sheffield, notes that another impact of the pandemic disruption is that it has been hard for teachers to predict student results with any accuracy - not least because the disruption had hit them so differently.

“Normally, you can predict quite well how exams are going to fall out in the summer and where your strengths will be, where students will fall short,” he says. “This year is full of uncertainties at every level in every different cohort.”

For example, he says GCSE students have seemed unmoved by the exams because they have been so disillusioned by their experiences over the past few years.

“Our Year 11s just seem less bothered about their examinations,” he explains. “They feel like they’ve been let down over a number of years and…what’s the point.

“We’ve had poor attendance in Year 11 in the run-up to the exams this year and that is mainly as a result of the impact of the pandemic.”

For A-level students, he says the opposite is true - they found exams “really traumatic”, not least because they had no prior experience from their GCSEs (because they received TAGs in 2021), and they are concerned about how the return to 2019 grading will affect their results.

“[They] are hyper-anxious about how they’re going to perform and the implications for them,” he adds.

Lee Elliot Major, professor of social mobility at the University of Exeter, says this anxiety is understandable as it will have been very hard for teachers to have predicted grades accurately for students on which they then made their university applications.

“I think there’s more uncertainty around predictions this year [and] there will be more students who miss out on their first choices if they slip a grade,” he says.

“It will be one of the toughest admissions rounds for years.”

In response to this concern, a spokeswoman for Universities UK says that while applying to university is “always a competitive process”, those who are administrating places understand the reality faced by different student cohorts.

“Admissions teams are experts at contextualising an applicant’s achievements and understanding what grading arrangements were in place when they were studying,” they add.

The DfE also says it is confident that universities will ensure a “fair process” takes place this year for all students.

Nevertheless, it could well be that come Thursday morning, schools will have to support many students in working out their next steps through clearing, appeals or resits if they don’t receive their anticipated grades.

Fears for the disadvantage gap

Of particular concern will be the impact of all this on disadvantaged students, with Elliot Major saying he fears the impact of the pandemic will show a widening of the attainment gap in terms of exam outcomes and onward study opportunities.

“Children from disadvantaged backgrounds suffered disproportionate learning loss during the pandemic,” he says. “I think it’s going to be stark for many years to come.”

Professor Becky Francis, chief executive officer of the Education Endowment Foundation, shares this concern, telling Tes that she expects exams to show “the attainment gap between pupils from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds and their classmates will have grown again”.

“This has serious implications for individual students’ life chances, as well as the fairness of our society as a whole,” she says.

The government should be aware of this, with DfE data last year revealing the gap in average A-level grades between poorer students and their peers in summer 2022 was the widest since 2016-17.

And there was a similar picture for key stage 4, as government data revealed that the disadvantage gap at GCSE had risen to its highest level in 10 years.

In acknowledgement of this, Dr Saxton also said last week that grading arrangements “have been made absolutely with disadvantaged students in mind”.

The DfE spokesperson says the department is confident this will ensure that access will remain open to all students, adding that last year saw “the highest number of disadvantaged 18-year-olds in England get into university on record”.

The spokesperson also says that Ofqual’s overall approach should ensure confidence in the results achieved this year for all students.

“This year, GCSEs, AS and A levels are returning to pre-pandemic grading arrangements, with protection built into the grading process to recognise the disruption students have faced,” they say. “This means a student will be just as likely to achieve a particular grade this year as they would have been in 2019, the year before the pandemic.”

A more nuanced approach

This stance also has a notable potential impact on schools and teachers as they know that the grades they help students achieve are now considered open for fair comparison to the 2019 outcomes, despite all the upheavals this cohort has suffered since 2020.

Given this, Sarah Hannafin, head of policy at the NAHT school leaders’ union, says that leaders across the sector should be mindful of this when analysing results data.

“The lower grades expected this year will be no reflection on the hard work of school staff and pupils, but simply a result of the government’s decision to return to pre-pandemic levels,” she says.

Mohsen Ojja, chief executive of Anthem Schools Trust (a trust with 16 schools, including five secondaries), says he agrees that the return to 2019 grading is right, but that he will be avoiding direct comparisons owing to the upheavals of the past few years.

“When looking at performance internally, we won’t be making hard comparisons between year groups but taking a more nuanced reading of the data,” he says.

Nick Soar, executive principal of Harris Academy Tottenham and Harris Academy St John’s Wood, has a similar view, noting that attendance issues alone will have affected many students across the past few years.

“The wider effects of lockdown, such as massive uplifts in persistent absence, remain and students with attendance lower than 94 per cent will perform poorly,” he warned.

As such, he said “any analysis of what the results mean in terms of how a teacher or department has done” will have to be “very provisional” and leaders should be “cagey” about reading too much into outcomes on exam result days.

EMET CEO McDonough also says he will “certainly” bear this in mind when analysing school results - but questions whether the accountability system around schools will do the same: “I don’t think those who externally assess school performance will take this into account.”

In response, an Ofsted spokesperson says: “We do not base our judgements on exam results, test scores or other data. We only use performance data as a starting point on inspection to inform discussion with schools about pupil outcomes.”

Ultimately, while the hope across the sector is that this year’s results days mark the first truly normal results days in several years, it seems clear that the pandemic’s impact on exams is very much here to stay. As ASCL president Forde says: “We are not past the legacy of Covid - I don’t think that can be underestimated.”

Additional reporting by Dan Worth

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article