Exams 2024: Why RAAC, P8 and the pandemic can’t be ignored

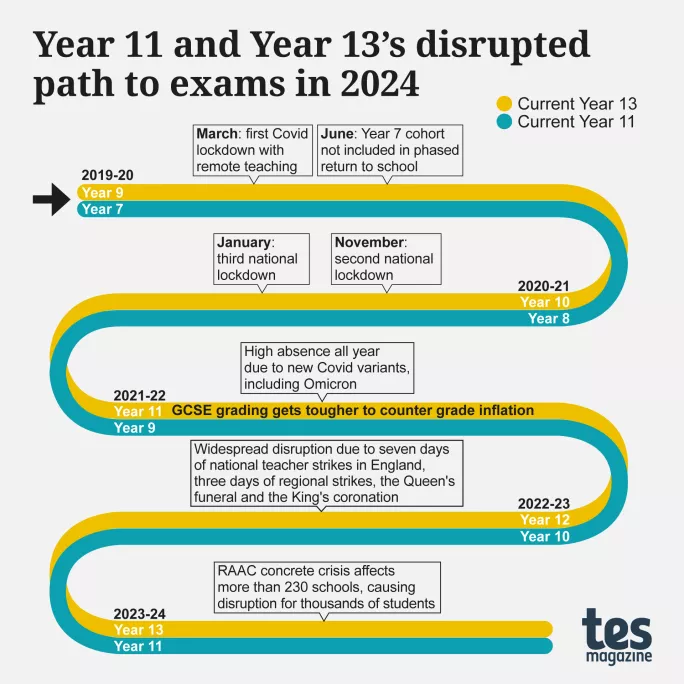

Last year’s GCSE and A-level exam cohorts were dubbed by some as the “unluckiest” ever because of the Covid pandemic’s impact on their studies and the lack of moderation to exam marking as in previous years.

This year’s students may want to stake their claim to that title, though. While they experienced the same pandemic disruption as the cohort before them, thousands more in schools built with reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) had to worry about the roof of their school falling down and the disruption caused by mitigations to prevent this.

For these students, there has not been a single “normal” year at secondary school - yet they have not received any moderation in exam marking either.

Although A-level students did have two normal years at secondary school, they too experienced a lot of upheaval and had their GCSE exams marked under the “glide back” in 2022.

Tom Middlehurst, qualifications specialist at the Association of School and College Leaders (ASCL), says while there had to be a return to standard exams, it is clear this year’s students have “undoubtedly faced significant hardship”.

“It was precisely for these students [that] the government’s own education recovery commissioner suggested a £15 billion investment in recovery and catch-up, which was rejected by the government at the time,” he adds.

Wrong year groups prioritised

Keziah Featherstone, headteacher at Q3 Academy Tipton, says she saw the impact of this first-hand with her GCSE cohort in particular and ponders whether, given the subsequent lack of support, she should have given them greater priority.

“When I was making decisions [during the pandemic] about which bubbles to send to home, we chose Years 7 and 8. So they lost two solid years [of schooling] because we felt we need to prioritise the exam cohorts coming through in Years 10 and 11,” she says.

“With hindsight, with CAGs [computer-assessed grades] and TAGs [teacher-assessed grades], you could say we probably didn’t need to prioritise them - but you just didn’t know what was going to happen.”

- Exam results: A-level results day 2024: all you need to know

- Entries: Maths to dominate exam results days

- Scotland: How did results differ between counties?

Meanwhile, for schools affected by RAAC, the past year saw huge disruption on top of everything that had come before, as Jamie Saunders, headteacher of Honywood School in Essex, recounts.

“We had to delay opening at the start of term and then could only have half the school in,” he says.

“So we had to go back to Covid arrangements and do remote teaching with a rota of a couple of year groups in at a time and the rest at home.”

Saunders says it was evident students in the exams years were affected by this latest disruption, but says there has been no leeway from exam boards - except potentially for coursework elements of certain subjects.

“I managed to make a case for those who had taken a [food preparation and nutrition GCSE] and the exam boards said they would modify there, but it has been very restrictive,” he says.

The primary-to-P8 conundrum

While all this means students may well feel aggrieved that they received no exam moderation, schools could also feel frustrated that their exam results will inform Progress 8 scores that measure outcomes between key stage 2 Sats and GCSEs.

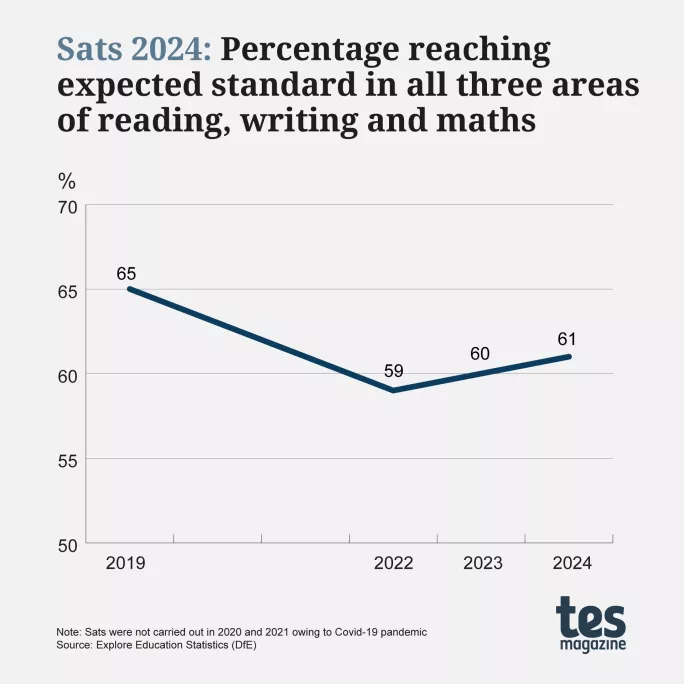

That’s because while GCSE students faced untold upheaval before sitting their exams, they took their Sats in the summer of 2019 after an entirely uneventful six years and scored far higher than pandemic cohorts - underlying the benefit of no disruption.

As such, for secondary schools having to build on this to GCSEs that then inform P8 scores is something that Featherstone says “feels like a kick in the teeth after everything we’ve done to try and rescue [their] education”.

She adds that because “in some areas pupils were in and out of schools a lot, while other schools were barely touched”, the impact will not be evenly distributed.

“There are schools that were better staffed or had better attendance, and then there are schools with historical, contextual factors, like high numbers of special educational needs or a substantial deprivation index,” she notes.

Katie Benyon, a statistician with FFT Datalab, agrees that the situation means there should be a “health warning” with P8 scores to remind people of the disruption faced by schools.

“Many people probably have it in their minds things are more normal now, so I think to highlight the journey the cohort has gone through [is important],” she says.

A cohort beset by problems

She says that for schools with RAAC, the impact will be particularly severe and need quantifying. “The young people who went to those schools and had to be doing online learning again and all that disruption is an important thing to highlight,” she says.

As the head of a school affected by RAAC, Saunders agrees that the impact must be recognised: “While obviously Covid had a bigger impact on a national level and all schools were affected to some degree, with RAAC you had some schools that were totally affected and some not at all.”

As if this wasn’t enough, attendance issues for Year 11 students have also been a real concern, with a report by Teacher Tapp noting a quarter (26 per cent) of secondary leaders were more concerned about Year 11 absence than they were at this time last year.

This echoes analysis by FFT Education Datalab that 28 per cent of Year 11 students were persistently absent during the autumn and spring terms, compared with 15 per cent over the autumn and spring terms in 2018-19, before the Covid pandemic lockdown.

A further study by the Nuffield Foundation also says the uneven impact of the pandemic meant children from low-income backgrounds experienced as much as two extra months of lost learning - meaning the disadvantage gap in assessment outcomes will widen further from 2024.

Despite all this, all schools will receive a “normal” P8 score that ignores the (uneven) impact of the pandemic, strikes, RAAC, absences or the fact that pupils arrived at secondary school with Sats scores achieved after an entirely uneventful primary education.

A three-year problem

This may all sound dispiriting enough, but here is the coup de grâce - schools will be stuck with this P8 score until 2027.

This is because there will be no P8 scores for the next two years owing to the fact no Sats were taken in 2020 or 2021, and so there is no data to track the progress of GCSE cohorts in 2025 and 2026.

“[Our P8 score is] going to inform people’s judgement of the school and it doesn’t matter if I do a really good job the following years, because there will be no data,” says Saunders.

Mindful of this, the previous government said in April it would publish the last two years’ P8 scores (2022-23 and 2023-24) achieved by schools before returning to P8 in 2027.

However, ASCL’s Middlehurst says that this is less than ideal, as it means schools are still being held accountable against scores achieved during some of the “most challenging” years in history.

“That is clearly invidious and the incoming government has to look again at assessment and accountability measures that are fit for the future,” he added.

John Jerrim, a professor at UCL Institute of Education, says the situation shows why he believes the P8 measure needs to move to a three-year average to factor in any disruption schools may face.

“This is probably one of those examples where this wouldn’t be such an issue if you were using three-year average measures,” he says.

“Things will always crop up that will impact a school’s performance in any given year outside of its control - you lose your great head of maths that you can’t replace quickly, for example.”

Meanwhile, Benyon at FFT acknowledges that the situation facing schools will no doubt contribute to the way P8 has been “maligned” in recent years - but says it is important we have a measure that “takes pupils’ starting points into account” to help track progress in the system.

Time for change

For Middlehurst, though, the fact that P8 has survived unscathed from the pandemic should never have come to pass.

“For two years during the pandemic, Progress 8 and other performance measures weren’t published, with no harm to the system - this was a real opportunity to rethink what intelligent accountability looks like and it has been missed.”

Jerrim agrees that change may now have to come. “The lesson here is how do we evolve the measures we have so they are robust to these potential issues,” he says.

The government seems to agree, with a DfE spokesperson saying that its curriculum and assessment review will “look at the current range of accountability metrics, including Progress 8, and how we can ensure the measures support a reformed curriculum and assessment system”.

Any changes will come too late for this year’s results, though - which means for heads such as Saunders, the task ahead is to ensure students, parents and the wider community understand the context within which the results were achieved.

“We’ll find our own way to communicate this to our community and share that context,” he says, before adding ruefully: “But we know many people just look at an overall number and say ‘that’s good’ or ‘that’s bad’…That’s something I am going into summer worrying about.”

For the latest education news and analysis delivered directly to your inbox every weekday morning, sign up to the Tes Daily newsletter

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article