GCSE and A-level results days: 8 trends to watch for

A-level and GCSE results days fall on 17 and 24 August respectively, and students all over England, Wales and Northern Ireland will pick up their envelopes or open their emails to discover what grades they have earned from their summer exams.

This year, the national pass rate of grade 4 and above for GCSE will “return to 2019 standards” - an objective set by Ofqual following the increased number of higher grades that were awarded during the two years of cancelled exams in 2020 and 2021. This unavoidable “grade inflation” occurred when teacher assessments were used in place of in-person exams.

- Results 2023: Top A-level grades up in private schools but down in North East

- GCSEs and A levels 2023: How will grading be different this year?

- Exams 2023: Results loom but is a return to 2019 standards fair?

To undo the grade inflation and return to pre-pandemic standards, Ofqual created a two-step plan.

The first step happened last year in 2022 when grade boundaries were more generous and resulted in national pass rates for GCSE and A-level that sat at a “midpoint between 2019 and 2021”.

Now, to close the gap completely, 2023 results will mark the second and final step back to pre-Covid grade distributions, with national pass rates of around 67 per cent expected for GCSE and 75.5 per cent for A level.

Speaking to Tes in May, Ofqual chief executive Jo Saxton explained that we will see results pass rates “as similar as possible” to 2019 and it will be achieved because exam boards will “take into consideration the disruption students have suffered” when setting grade boundaries.

Saxton explained that “even if the quality of student work is slightly weaker at a national level within a subject”, results will be “as similar as possible to those of 2019”.

In short: even though student performance in 2023 will be below what happened in 2019, the grade boundaries will be set to ensure the number of students passing their exams and the distribution of grades will be very similar.

So, what might all this mean for the latest summer series? We pick out eight trends to look out for on results days:

1. Fewer top grades at GCSE

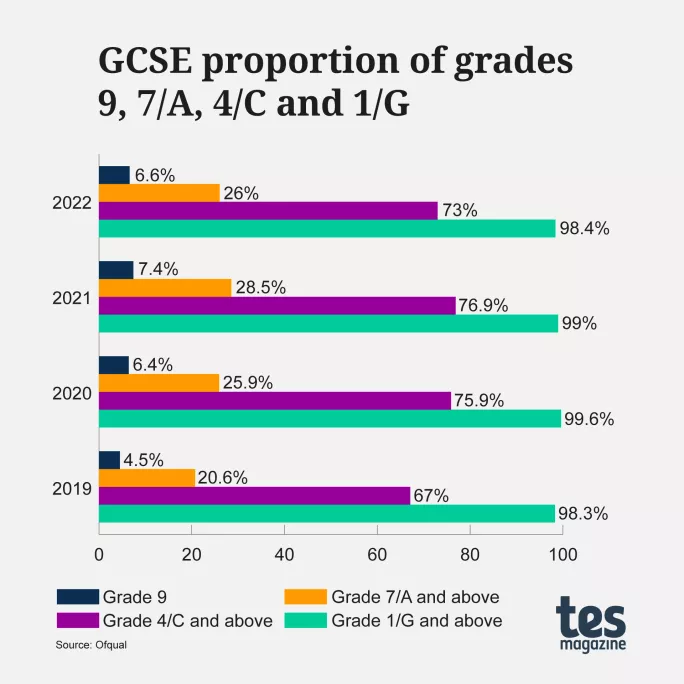

As the chart below shows, when using teacher-assessed grades (TAGs) in 2021, the pass rate for grade 4 and above was 76.9 per cent, 9.9 percentage points higher than the pre-pandemic standard of 2019 to which Ofqual says grades need to return to.

Looking at the average for all GCSE subjects, the gap between the 2019 and 2021 averages for grade 9s was 2.9 percentage points.

Last summer, the gap was closed by just 0.8 percentage points, when 6.6 per cent of all grades were awarded grade 9.

This means that, in 2023, the number of grade 9s being awarded needs to drop by 2.1 percentage points to bring it to 2019 levels.

So, what might this look like on results day?

Well, for schools whose cohort is of a similar ability to the previous year’s, they know that their percentage of students achieving grade 9s is likely to be lower.

For schools that have more students on course to achieve top grades this time around, the 2.1 percentage point drop is likely to be felt even more sharply.

2. Top grades at A level will be harder to achieve

In a similar pattern to GCSE, A-level grades will also have to see a proportionally larger reduction at the top end in order to achieve Ofqual’s target of 2019 grade distribution.

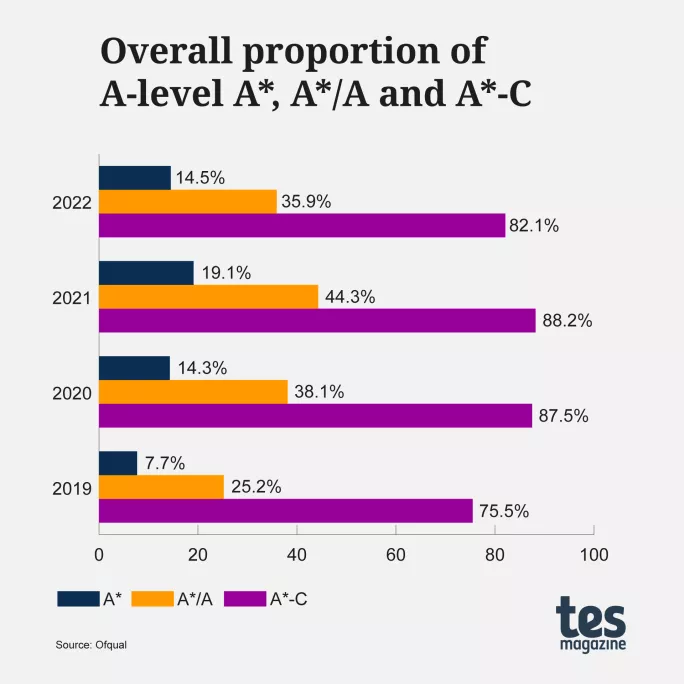

As the chart below shows, in 2019, only 7.7 per cent of grades awarded were A*, and this is the standard expected to return this summer.

In 2021, it had jumped by 11.4 percentage points to 19.1 per cent.

In the first step of the return to pre-pandemic standards in 2022, there was a 4.6 percentage points drop, taking the number of A*s awarded to 14.5 per cent.

However, this means that this year, there will need to be a greater drop of 6.8 percentage points to achieve the 2019 proportion of A*s.

Similarly, the number of grade As is also expected to see a greater drop in 2023 compared with 2022 in order to return to the 2019 distribution of grades.

However, this doesn’t mean that students are being “downgraded”; instead, if necessary, students are being given more generosity in the grade boundaries.

Ofqual explains using an example of a student whom you would normally expect to be a B-grade candidate.

”This means that a student who typically would have achieved a grade B in their A-level geography before the pandemic will be just as likely to get a B this summer, even if their performance in the assessments is a little weaker,” a spokesperson says.

“The return to pre-pandemic grading means that national results will be lower than in 2022.”

3. A drop in top GCSE grades by subject

For some subjects, the move back to 2019 standards will require a bigger jump than others.

Ofqual says that “results for individual subjects will vary, as they do in any year” and that grade distribution “depends on the cohort of students taking the qualification and how they perform in the assessments”.

This year, as with every year, there is no set quota of grades, nor a cap on the number of students who can get a particular grade in any subject.

However, when we look at the results from last year, if the ambition of returning to the grade distribution standards of 2019 is to be realised, then it’s clear some subjects have further to move than others.

GCSE English language, modern foreign languages and computing will all require fewer students to achieve the top grades than did so last year in order to achieve the aim of the 2019 grade distribution.

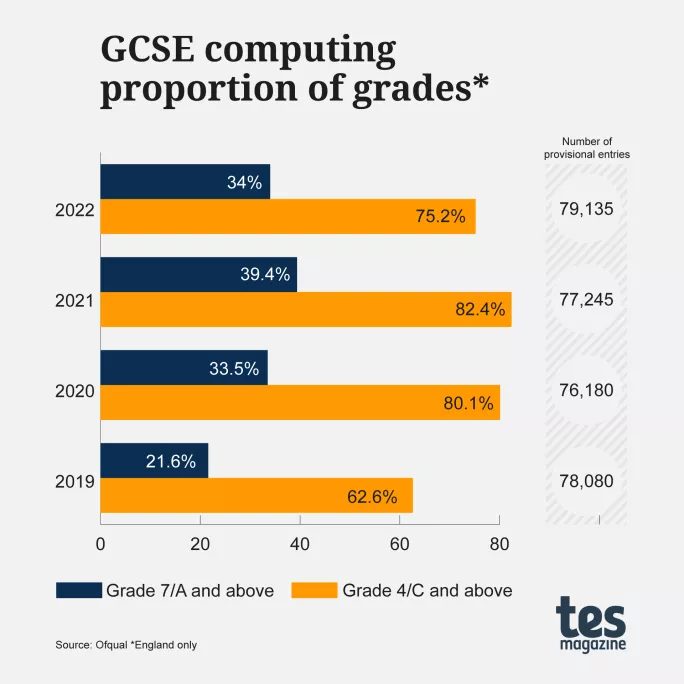

The subject with the most significant gap to close is computing.

In 2019, the percentage of students scoring grade 7 and above in computing across England, Wales and Northern Ireland was 21.7 per cent.

When TAGs were used, this grew to 39.7 per cent, leaving an 18 percentage point gap.

In the last summer series, this gap was only closed by 5.6 percentage points, resulting in a 12.4 percentage point gap to close in 2023.

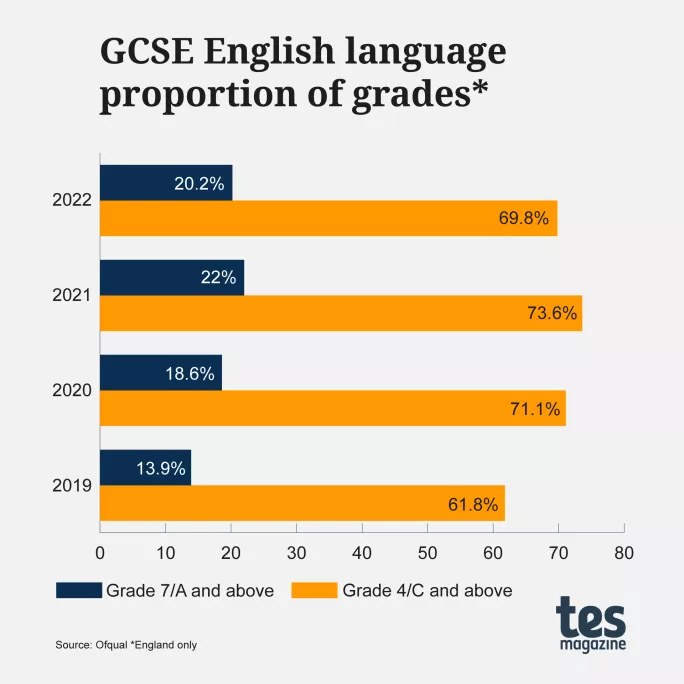

In the case of English language GCSE across the UK, a drop of 8.2 percentage points will be required to bring the grade 4 and above percentage down, and 6.4 percentage points to do the same for grade 7 and above.

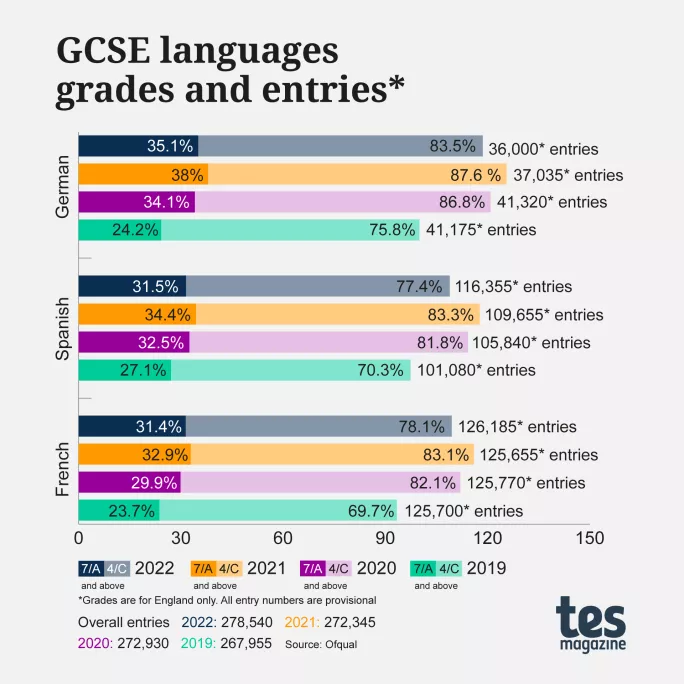

German GCSE requires a 10.9 percentage point drop to close the gap for grade 7s in all three nations. This follows a far smaller drop in 2022 of just 3 percentage points.

However, it is important to note this may be affected by the changes made to the awarding of grades in MFL to bring French and German in line with Spanish.

4. The disadvantage gap will widen at GCSE

In 2022, the GCSE performance gap between students on free school meals and those not widened when the key stage 4 disadvantage gap index rose from the previous year (from 3.79 to 3.84).

Data revealed that the gap between the poorest students and their wealthier contemporaries was now at its highest level since 2012.

This year, following higher rates of absence among FSM pupils, that gap is expected to widen further.

In 2021-22, 37.2 per cent of disadvantaged pupils were persistently absent across the year, compared with 17.5 per cent of pupils who were not eligible for FSM.

However, the size of this gap will not be revealed on results day itself. Although schools will be able to see how their own FSM students performed, the full picture will only be seen when national data is released in the autumn.

5. The divide between North and South is likely to grow

In 2022, the gap between the GCSE performance of students in the North of England and students in the South widened.

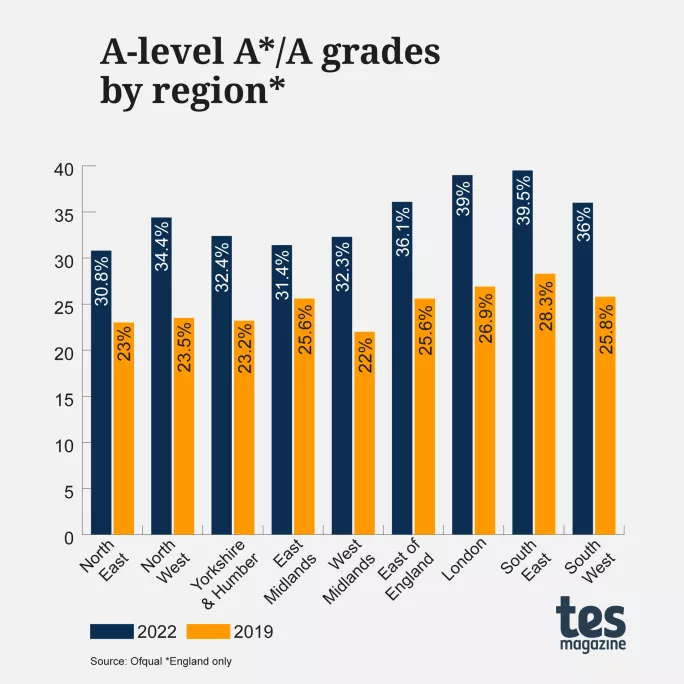

A-level results also revealed significant regional differences in student performance, particularly at the top end of grades.

Looking specifically at A/A* grades, we can see that in the North East, the proportion of students achieving these top grades was 30.8 per cent, compared with 39.5 per cent in the South East, a difference of 8.7 percentage points.

This gap had grown by 3.4 percentage points since 2019, when the figures were 23 per cent for the North East and 28.3 per cent for the South East.

Tes detailed the challenges facing schools in the North of England in our piece exploring the reasons behind the attainment gap. Since this was written, no significant policy changes have addressed the root causes of the problems exposed here - and consequently, the performance gap is expected to widen.

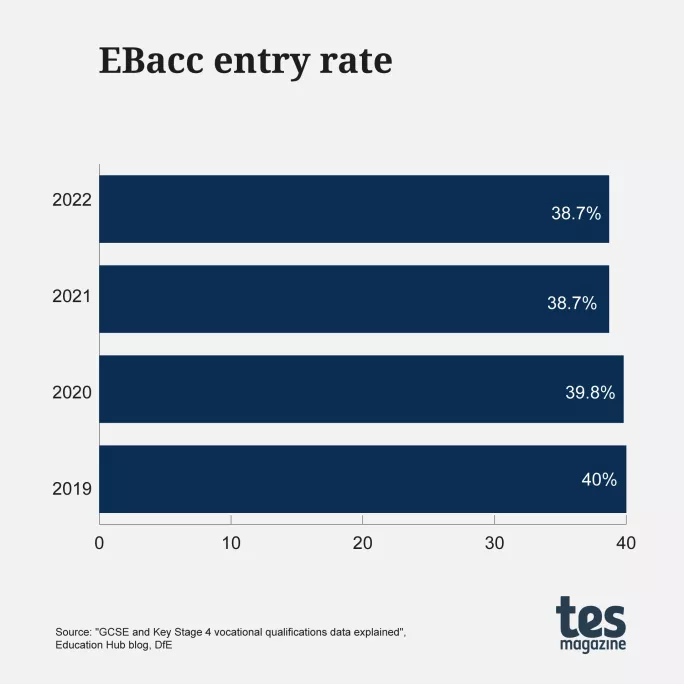

6. Entries in EBacc subjects are up - will this help the EBacc measure?

The number of students being entered for the English Baccalaureate combination of subjects has been declining since 2019 - an issue that has not been helped by the declining number of MFL teachers.

This year, there has been a 3.6 per cent increase in the number of students taking GCSEs, and also a 4 per cent rise in the number of EBacc subjects being studied.

Will this convert into a higher number of students studying the EBacc combination? We will have to wait and see.

7. Spanish, computing and home languages continue to grow in popularity at GCSE

While German entries are down by 5.7 per cent and French saw a marginal increase in entries of 0.3 per cent, Spanish continues to attract more students with a rise in entries of 4.6 per cent, and continues to be the most popular MFL to study.

However, last year’s provisional entries did not convert into actual examinations completed.

The reason behind this gap was not clear. However, one explanation could be an increase in the number of students dropping a subject in the run-up to taking the exams in order to prioritise other subjects. We wait to see if that trend continues this year.

Computing and home languages have also seen considerable rises in the number of students entered for exams, with computing rising by 11.9 per cent and home languages by 8.1 per cent.

8. The National Reference Test will reveal the impact of home learning

The year group currently waiting for GCSE results had only one full year of secondary education before the first national lockdown disrupted the schooling of children across the country.

Last year, the National Reference Test results revealed that although maths had a statistically significant decline, the performance in the English test was comparable to the last cohort who took the tests in 2020 (before lockdown moved learning online).

This year, because this cohort spent less time in their secondary schools before the first lockdown, we might see something different in the results.

The current cohort has lost proportionately more time while preparing for their GCSEs owing to the disruption of home learning and higher rates of absence, so it’s possible we’ll see more of a decline compared with pre-pandemic levels.

The National Reference Test was taken by selected students in February and March 2023 and the results will be published on GCSE results day (24 August). Tes explains the test’s purpose and how it’s used to set grade boundaries here.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article