GCSEs and A levels 2022: 8 trends to expect on results day

GCSE and A-level results days will take place later this month, marking the first “normal” set of exam outcomes since 2019, after Covid-19 disruptions resulted in the use of centre assessed grades (CAGs) in 2020 and teacher assessed grades (TAGs) 2021.

Specifically, A-level results will come out on Thursday 18 August 2022 and GCSEs on Thursday 25 August 2022.

While exams have been sat as normal, there were some minor tweaks to adjust for the learning loss experienced during lockdown.

So, what will this mean for the disadvantage attainment gap? Or for the uptake of Stem (science, technology, engineering and maths) subjects by female students? And how will attempts to tackle grade inflation impact the final grades?

We take a look at these topics and more in our insider’s guide to the issues that teachers and schools will have on their radar for August and beyond:

1. There will be a significant drop in top grades

The GCSE and A-level results from 2021 were the highest on record, with a particular leap at the top end in terms of the proportion of As and A*s awarded at A level.

In England, nearly 1 in 5 (19.1 per cent) of entries were awarded an A* grade, while more than two in five (44.3 per cent) were awarded an A or A*.

And at GCSE, 28.5 per cent of entries were awarded a grade 7/A or above, while 7.4 per cent scored the top grade of a 9.

We know that Ofqual will be using 2022 as the first in a “two-step return” to 2019 standards and that, in 2022, grading will be pegged to a midpoint between 2021 and 2019 but below 2020.

However, to do this, unlike the disastrous intervention of 2020, this year there will be no algorithm used to try to reduce grade inflation and return the distribution of grades to 2019 levels.

Without an automatic adjustment to the grades to ensure the 2022 cohort aren’t awarded grades that are significantly lower than the past two years, how will they do it? And will it work fairly?

Speaking to Tes earlier this year, Ofqual chief Dr Jo Saxton explained the process, as follows: “There is no quota of grades and we have not predetermined grades. What we have asked the boards to do is mark as normal and then apply the grading process.”

Saxton went on to explain that during the awarding process (where grade boundaries are set), Ofqual will be “lowering the bar” and won’t be expecting students to “meet the same performance standard as in previous years”.

In short, grades will be going down (see points 2 and 3 below for how much).

Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, says schools need to brace themselves for this reality but he fears many are unaware of how hard this will hit.

“I worry about the high proportion of teachers that I speak to who have not yet fully recognised the desire within Ofqual and Whitehall to push back on the Covid-related grade inflation,” he says.

“The plan is to reverse half of the Covid-related grade inflation this year and the rest next year. So we could see a really significant gap between teachers’ expectations and the reality when results land.”

- Grading: GCSEs and A-level Grading: Ofqual explains what you need to know

- GCSEs 2022: Teacher grades ‘bias’ legal battle looms

- Exams 2021: Record high results for GCSE and A level 2021

Research conducted by the Sutton Trust revealed that students are also worried that the mitigations to exams won’t be enough to secure them the grades they need to progress.

Only 52 per cent of Year 13 students felt the arrangements for exams this year had fairly taken into account the impact the pandemic had on their learning.

Jon Andrews, head of analysis at the Education Policy Institute (EPI), says that, overall, Ofqual’s approach this year is “reasonable” but the concerns about fairness that students have outlined also have merit.

“What it does mean is that this year’s students may be competing for places at university against pupils from earlier cohorts with higher results.”

2. A-level grades will see bigger changes than GCSEs

As explained above, in 2021 it was A-level grades, rather than GCSEs, where we saw the most significant inflation.

Therefore, logic follows that when we see this two-step return to the 2019 standard, the stride required for the A-level step is going to be larger than that required for GCSE.

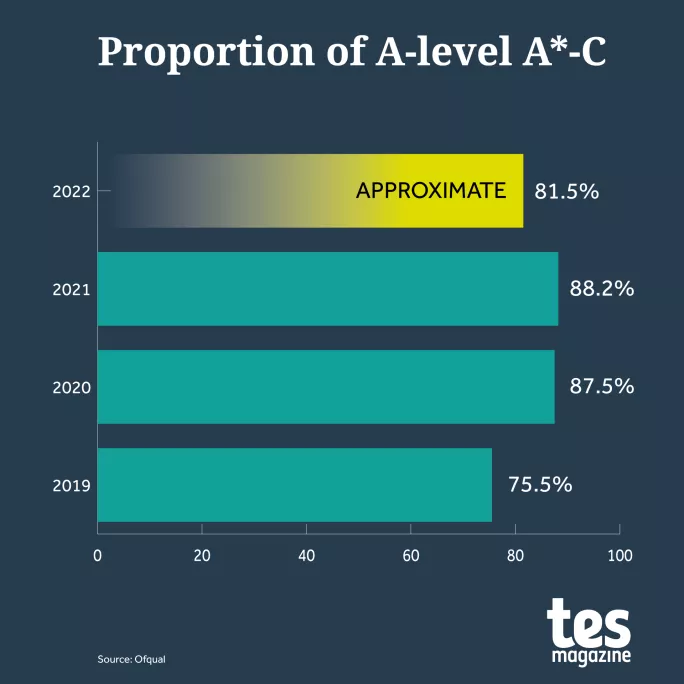

If we look at the A*-C measurement, in the table below, we can see that in order to take two steps down to 2019 levels, we’re looking at a drop of 6.35 percentage points for A-level grades at A*-C.

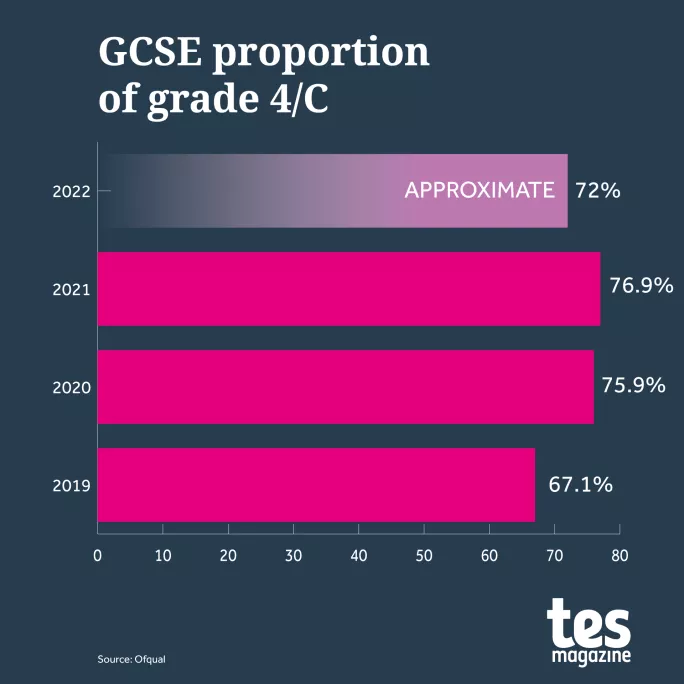

Compare this to GCSE and we see a slightly different story. As the table below shows, we would only need a decrease of 4.9 percentage points to make the first of a two-step drop back to 2019 levels of achieving grade 4 and above.

This point becomes even more pronounced if we look at the top-end of grades. In 2021, A levels saw an increase of A/A* grades to 44.3 per cent from 25.2 per cent in 2019, whereas at GCSE, the number of grade 7/As only rose to 28.5 per cent in 2021, up from 20.7 per cent in 2019.

This means that on results day, we can anticipate a drop in the top grades for A level of 9.55 percentage points compared with just 3.9 percentage points for GCSE.

3. There will be regional differences in results

The regional attendance figures for the past year, revealed by Tes, also expose disparities in absence rates for the current GCSE exam cohort. Year 11 students in the northern regions missed around 15 per cent of school sessions compared with around 11 per cent in the South.

Given this, Dave Thomson, chief statistician at the FFT Education Datalab, says there will “be a [regional] difference because the impact of the pandemic has been uneven”. However he does not think it will be “massive”.

“There are usually differences in regions,” he says. “I predict that when we compare 2022 to 2019, it will look like some regions have been impacted more than others. London will be the least affected as that has been lower than the rest of the country.”

Bill Watkin, chief executive of the Sixth Form Colleges Association, also warns that without the old “value added” context, looking at results at a “local level” - where there are geographical differences - might lead people to draw the wrong conclusions.

“The absence of value-added measures in the next round of performance table means there will be more focus on attainment - and that also could take some explaining at a local level,” Watkin explains.

“One institution might look like it has done very well because of the nature of its student socio-economic and ability profile, while another might seem to have done less well, though they may have achieved remarkable success with a more inclusive population, facing bigger barriers to learning.”

Some schools leaders have already said they will be wary of promoting their overall results too loudly, given the fact that every school will have experienced the pandemic differently.

4. The disadvantage gap will increase

Furthermore, although 2020 saw a “shrinkage” of the disadvantage gap when CAGs were used, last year, the gap widened again when TAGs were used.

The widening has been attributed to the fact that disadvantaged families were more likely to have faced difficulties when trying to learn from home during lockdown.

So, what can we expect this year? Unfortunately, more of the same.

Exam-year cohorts have experienced more disruption to their schooling with disadvantaged pupils have faced adversity for a longer period.

Online learning forms part of that disruption but data shows that disadvantaged pupils have also had higher levels of absence.

In May, data from FFT Education Datalab revealed that since the start of Year 11, pupils missed 11.1 per cent of sessions but it was disadvantaged pupils who were more likely to be absent.

Disadvantaged pupils missed 17.1 per cent of morning and afternoon registration sessions compared with 9.6 per cent of non-disadvantaged.

This equates to approximately 12 extra lost days across the whole year.

It’s a similar story when we look at persistent absence, with a shockingly high 9.9 per cent of disadvantaged pupils missing more school than they attended, compared with 3.7 per cent of their peers.

So, does this mean we can expect the disadvantage gap to widen on results day?

Simon Burgess is a professor of economics at the University of Bristol, and says he believes the gap will grow.

“Comparing this year to pre-pandemic, from what we’re seeing in terms of key stage 2 and primary-age online assessments, it seems likely that the disadvantage gap will increase, possibly quite markedly,” he says.

However, he says we should be comparing 2022 to 2019, rather than using TAGs or CAGs.

“It’s very hard to say how it will be relative to the two intervening years because the basis for those marks has been so different.”

However, there is some caution about how we interpret the 2022 data.

Thomson says that owing to changes to free school meals (FSM) eligibility, the answer isn’t quite as straightforward as you might think.

This is because in the past, only pupils eligible for FSM in Year 6 would continue to be counted in the pupil premium group all through secondary school. If they ceased to be eligible before Year 6, they wouldn’t be counted in the pupil premium group when they were in Year 11.

However, under the new measures, every pupil who was ever eligible for FSM in primary school will continue to be counted in the pupil premium group when in Year 11.

Thomson says that as a result, we need to keep this in mind when looking at the gap.

“If we hadn’t had changes to FSM eligibility, then I would say, yes, the gap will widen,” he explains. “But we have made changes to who qualifies for FSM so that means we have children included in the FSM 6 group who wouldn’t be included before.”

As a consequence, Thomson says working out if the gap is widening or narrowing is no longer “straightforward” and that “the gap could look like it is closing but that would be because we’re not comparing like for like”.

Overall, Andrews says addressing these issues must be a top priority across all of government.

“One of the drivers of geographic differences is the varying prevalence of persistent poverty in these areas and, most worryingly, persistent poverty is on the rise,” he says.

“This isn’t just an issue for schools or the Department for Education. It’s imperative that a cross-government child poverty strategy be introduced if we are serious about reducing inequalities and ‘levelling up’ across the country.”

5. Girls will continue to be entered for more Stem subjects

There has been a continuous push for more girls to join their male counterparts in A-level Stem classrooms for some years now, and the success of this can be seen in the increased numbers of girls taking Stem subjects at A level.

However, analysis of the 2021 results reveals that although broadly looking at all Stem subjects, we seem to be reaching equal entry - with girls accounting for 50.3 per cent of entries in biology, chemistry and physics in 2021 - a closer look at the data tells us we still have some way to go before we can consider that gap to be entirely closed.

The Campaign for Science and Engineering (CaSE) wrote about this gap in its blog on the topic last year, saying that despite girls outnumbering boys in biology, chemistry and physics since 2019, a “subject-by-subject approach reveals a very different picture”.

“Computing (15 per cent), physics (23 per cent) and further maths (29 per cent) have the lowest proportion of female students of all A-level subjects, with psychology (74 per cent) and biology (64 per cent) doing the heavy lifting in rebalancing the divide,” it says.

So, what can we expect in the 2022 results? Daniel Rathbone, assistant director at CaSE, says he isn’t expecting much to change.

”CaSE will take a close look at this year’s A-level results but trends haven’t changed much over the past couple of years,” he explains. “At CaSE we believe high-quality science education is crucial to driving forward the government’s plans to grow and ‘level-up’ the UK economy.”

6. Girls and boys will continue to ‘avoid’ English literature and language A levels

Last year, we reported on the slow decline of entrants to English-based A-level subjects. It looks likely that the trend will continue for 2022.

Sam Tuckett, senior researcher for post-16 education and skills at the Education Policy Institute, said: “Provisional entry data from Ofqual shows another stark decline in entries to English literature compared to last year, marking the continuation of a very worrying trend.”

There are several reasons for this: there is still a big push for Stem subjects and the perception that earnings are lower for those who study humanities remains. The “unpopular” new-style English GCSE is still in place and the same funding rules are in place that result in students being encouraged to do three, instead of four, A levels.

Although the news that several universities will be dropping their English degrees won’t have affected the subject choices for this year’s A-level students, it is an indicator that the study of English is losing popularity.

Tuckett says the government should take action if the data is as bad as feared.

“Ultimately, falling numbers of students pursuing the subject at this level could well result in falling numbers of teachers entering the profession to teach it, threatening the pipeline of English literature teachers for the years ahead.

“The government must examine the reasons for the subject’s declining popularity and, if necessary, take action to prevent future teacher shortages in this area.”

7. Pressure on universities

As noted earlier, A-level students hoping to continue their studies at university this September could find themselves competing with more students than usual.

There has been concern that the combination of a record breaking number of applicants to university, plus the increased number of deferrals in 2021, might mean that competition for places, particularly for popular courses, is particularly fierce.

In The Sutton Trust report, it quoted data released by Ucas that showed not just a drop in the offer rate but that, in competitive subjects like medicine and dentistry, only 16 per cent of applicants received an offer this year compared with 20.4 per cent in 2021.

When it comes to finding a place through clearing, Hillman warns that students might need to be open minded when considering courses.

“Some students may have to be more flexible than they initially planned,” he says. “Uber-selective institutions will remain very hard to get into and may be even harder than in some other recent years.”

Tuckett says schools and pupils should be ready to act on results day.

“As clearing services will likely be busier than usual in the fallout following results day, students going through clearing should act quickly to ensure they don’t miss out.”

Also, if you were counting on Brexit to have reduced the number of international students to make way for domestic places, Hillman says this won’t be the case.

“International student numbers are healthy so there is also a lot of demand from abroad. But, in general, international students do not take places from home students as is commonly believed. In fact, the opposite is often true - in other words, many courses are only viable to put on at all because of the presence of international students and the considerable fees that they pay.”

However, despite this, owing to the way university places are allocated, Hillman isn’t overly worried about university admissions, saying “many institutions have the capacity to grow beyond their current size” because of the dropping of “strict student number caps”.

8. The first year of T-level results will be revealed

This year, the first T-level results will come out but, owing to the staggered roll-out, only 10 courses will be included. T levels are graded “pass”, “merit”, “distinction” and “distinction*”. A distinction* is the equivalent of 3A*s at A level (168 Ucas points).

Lisa Morrison Coulthard, research director at the National Foundation for Educational Research says a recent survey undertaken by her organisation on behalf of the Department for Education shows T-level students have been “very positive” about their experience.

Coulthard adds that the T-level results need to be analysed in the context of the number of pupils studying on the courses.

“When looking at the grades and experiences of the first T-level students, it is important to consider how representative of future intakes they may be,” she says.

“Covid-19 aside, the class sizes were considerably smaller, with less competition for industry placements and considerable focused support from good to exceptional course providers.”

Tuckett says the outcomes will also provide the first proper chance to assess how T levels are being engaged with - and any potential issues that remain.

“The government removed the English and maths ‘exit requirement’ from T levels but, with many providers still requiring level 2 or above English and maths on entry, the extent to which maths and English requirements might prove a barrier to those completing T levels remains uncertain,” he says.

“There have been concerns about the availability of work placements required to complete T levels and, although results-day data is unlikely to shed light on this, this summer’s results season should give the first indication of completion rates as the roll-out in more subject areas continues.”

Given all of the above, it clearly won’t just be students and teachers watching on nervously when the results are revealed. For those shaping the direction of the education sector, there will be much to ponder and dissect.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article