What schools need to know about the KS4 performance data

Key stage 4 performance data and school league tables have fully returned after a three-year hiatus, albeit with a caution against comparing schools given the ongoing disruptions caused by the pandemic.

The data holds a raft of insights, trends and revelations that schools should be aware of. So, what can we learn from it? Tes has picked through the important statistics to give you the information you need.

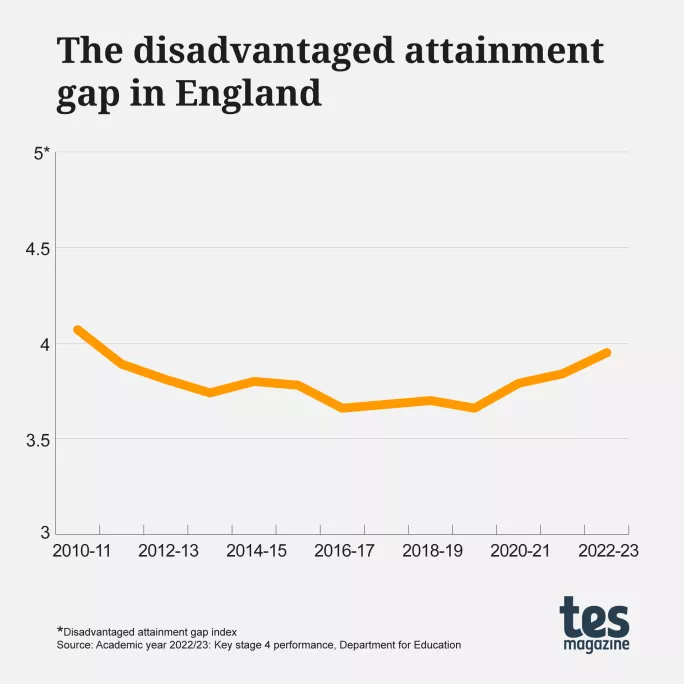

Disadvantage gap widens

The KS4 disadvantage gap index has widened to 3.95. This means the gap between disadvantaged and advantaged students is now at its widest since 2011.

The index is calculated using the average grades achieved in English and maths GCSEs between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged students.

Disadvantaged students are classed as being eligible for free school meals at any point in the past six years (from Year 6 to Year 11), looked after for at least one day or recorded as having been adopted from care.

To see how that gap translates into grades, we can look at the difference in percentages of students achieving a pass - grade 4 or above - in both English and maths GCSEs.

Before the pandemic, 44.7 per cent of disadvantaged students achieved grade 4 in English and maths, compared with 71.8 per cent of non-disadvantaged students.

This year, despite students having “generosity” built into the awarding process and a national pass rate above 2019 levels, disadvantaged students actually saw their pass rate decrease by 1.6 per cent to 43.1 per cent.

Their non-disadvantaged peers, on the other hand, saw their pass rate in English and maths at grade 4 increase to 72.6 per cent.

‘Bolder action’

The widening gap was met with dismay by sector leaders, with the Association of School and College Leaders’ Geoff Barton saying it was “heading squarely in the wrong direction” and required urgent action.

Emily Hunt, associate director for social mobility and vulnerable learners at the Education Policy Institute, agreed that ministerial action must be taken to stop educational inequalities due to poverty getting even worse.

“Any incoming or returning government needs to take bolder action to tackle deep-seated educational inequalities,” says Hunt.

“Our analysis shows that [educational inequalities are] evident - and indeed widening - even for the youngest children who have only just started school.”

Meanwhile, James Bowen, assistant general secretary of the NAHT school leaders’ union, said support for other social services that support children in poverty must also improve.

“This isn’t just about schools alone. Services like social care and mental health support have suffered from chronic underfunding over the past decade and this has an impact on students too.”

EBacc entries stagnate

The English Baccalaureate (EBacc) is a combination of subjects including English, maths, science, history, geography and modern foreign languages.

The Department for Education has set a target of 75 per cent of students entering exams in EBacc subjects in 2024, and 90 per cent in 2027.

However, today’s figures reveal that schools are no closer to meeting that target, with 39.3 per cent of students taking an EBacc combination of subjects this year - a figure just 0.6 percentage points higher than last year’s and down on 2019’s peak of 40 per cent.

Languages continue to be the stumbling block, with 88.9 per cent of students missing the language component in 2023, an increase of 1.4 percentage points on last year and 2.9 percentage points on 2019.

George Leckie, senior lecturer in social statistics at the University of Bristol, says the language data shows that a new direction may be needed if EBacc uptake is to reach the government’s goal.

“Scrapping the EBacc is one possibility, but less dramatic changes would also shift the system in a better direction,” he says, “most obviously by increasing the range of eligible qualifications.”

Regional differences remain stark

When comparing performances between regions, it’s clear the North-South divide continues to persist. Comparing the North East, whose average Progress 8 score is the lowest in the country at -0.27, and Outer London, which has the highest at 0.30, we find a gap of 0.57.

This is a problem that has grown since the pandemic. In 2019, the gap was smaller at 0.48, with the North East (-0.24) and Outer London (0.24) also the lowest- and highest-performing regions, respectively.

When we break this data down by local authority, we see even more variation in performance.

When looking at those achieving a grade 5 or above in both English and maths, there is a 49.8 percentage point difference between the lowest-performing (in the North) and highest-performing (in the South) authorities.

Not the full picture

However, academics have previously warned against basing too much on the P8 scores achieved, with Stephen Gorard writing on Tes earlier this year that the data tells only part of the story.

“The best evidence, which compares like with like, suggests that schools in the North produce comparable outcomes to schools in the South, for equivalent students,” he wrote.

Gorard’s research looked at 14 school cohorts and followed them over 11 years at school, using their 8 million records in the National Pupil Database.

“Once student background (and prior attainment, where available) is factored in, there is no difference in attainment between schools in the North and the South,” he continued.

Nevertheless, the fact that the gap between regions has widened during the pandemic and remains so wide between some areas will likely be of note to policymakers.

EAL students’ progress

Students with English as an additional language continue to make more progress than their non-EAL counterparts.

This year, the average P8 score for EAL students was 0.51, whereas non-EAL students averaged -0.12.

In GCSE grade terms, this means that, on average, EAL students progressed half a grade more than expected when compared with students with similar prior attainment.

Non-EAL students achieved a tenth of a grade less than students with similar prior attainment.

The progress achieved for these students can be explained in part by the progress of their language acquisition, and the difference in their language skills at KS2 and KS4.

However, as this FFT Education Datalab blog post explains, there are other complexities that should be taken into consideration - for example, the number of EAL students for whom there is no KS2 data as they arrived in the country in Year 7 or later and therefore are not included in the P8 data.

Difference in progress for boys and girls

Once again, there is a performance gap between girls and boys.

The average P8 score was 0.12 for girls but -0.17 for boys.

This means that, when compared to students with similar prior attainment, girls achieved a tenth of a grade more than expected, and boys nearly a fifth of a grade less.

This broadly mirrors the performance in exam outcomes, where girls generally outperformed boys across most subjects.

Attainment 8 drop explained

As expected, this year’s exam results were lower than the previous three years’ owing to Ofqual’s “soft landing” approach to returning exams to normal following the disruption of Covid.

This meant the average Attainment 8 score (calculated by taking an average of a student’s top eight GCSE grades) dropped to 46.2 - far lower than the average scores achieved in the pandemic years.

However, this is lower than pre-pandemic levels, too - in fact, it’s the lowest average A8 score since data was made available from the DfE in 2014-15.

However, Dave Thomson from FFT Education Datalab says that comparisons cannot be fairly made owing to the way grading was run before the pandemic.

“The A8 scores in 2017-19 were still subject to a phased introduction of 9-1 grades,” he explains. “Therefore, it isn’t really comparable [with what we have now].”

And, of course, in the pandemic years, grades were widely different owing to the use of centre-assessed grades and then teacher-assessed grades. As such, the only really fair comparison is with 2019, when the A8 score was 46.7 - only 0.5 higher than this year’s.

Nonetheless, keeping tabs on this data point in the coming years will become more important to track student progress over time.

League table wording

A notable difference to the way the league table data has been presented this year is the change in wording on the website when accessing school exam results.

The previous warning actively discouraged people from comparing schools because of the impact of the pandemic, with a large red box containing the below warning appearing during any search of schools or trusts:

Now, though, a slightly softer warning appears, in a black box:

Despite still providing this caveat to website visitors, the government has reverted to calling the service “Compare school performance” rather than “Find school performance data”, which it had switched to in a further effort to discourage comparisons.

Whether or not the new caution dissuades people from drawing comparisons between schools remains to be seen.

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article