Why does the DfE think we need fewer maths teachers?

When the latest initial teacher training (ITT) data dropped last month, it made for sobering reading.

Secondary trainees were sitting at 40 per cent below the government target, and a number of subjects, such as physics and computing, reported serious shortages.

However, among all the disappointing figures, one subject seemed to be doing surprisingly well, at 91 per cent of its target: maths.

But a closer look at the 2022-23 ITT targets subtracts some of the mystery from the surprising performance: the Department for Education (DfE) has reduced its quota for maths trainees by 27 per cent, from 2,800 to 2,040

It wasn’t the only subject to see a decrease - business studies and art did, too - but maths was the largest.

This is perhaps strange when you consider that in 2020-21 and 2021-22, the DfE targets for maths were not met, with a combined shortfall of 631 over the two years.

So, why change this year to reduce the target by another 760?

Show your working

The reasoning behind this move, says the DfE, is the increase of existing maths teachers joining the workforce through various channels.

“While the 2020-21 and 2021-22 PG (post-graduate) ITT targets for mathematics were not met, the impact of this under-recruitment was more than offset by increases in the numbers of PGITT trainees, returners and teachers that are new to the state-funded sector being recruited. Furthermore, there was an increase in the proportion of mathematics trainees entering the workforce immediately after ITT.”

It seems likely too that the increase is also partly driven by the higher numbers of deferred entrants caused by the pandemic as teachers who delayed entering work now do so.

However, while this may sound like the case closed, not everyone thinks the rationale adds up.

Jack Worth is the school workforce lead at the National Foundation for Educational Research. He says this “brief explanation” does not make it clear “which of these factors are the biggest drivers of this change” making it hard to know if the scale of the drop is realistic against the apparent gains.

Worth also highlights that it was October 2019 when the DfE last published its underlying modelling of the post-graduate ITT targets and, given the notable drop in the target this year, says the DfE should publish the full Teacher Workforce Model so the rationale behind these decisions can be better understood.

He’s not the only one with concerns. Pinky Jain is a committee member for the Association of Maths Education Teachers, a body for those working in the maths ITT sector. She also queries the decrease in the target.

“Though we have recruited better this year, there is still an overall shortage of maths teachers,” says Jain.

This is a problem that is “likely to be compounded in the coming years”, she says, pointing to the outcomes of the market review, which saw huge cuts in the overall number of places for teachers to train.

However, Professor Geraint Jones, executive director and associate pro vice-chancellor of the National Institute of Teaching and Education (NITE), is more bullish on the situation, noting that maths is the institute’s second most popular subject after PE.

He says, too, that the lower target won’t make a difference for NITE and it will continue to push to recruit as much as possible.

“As long as there is no cap on numbers for maths ITT recruitment, then the reduction in target makes no real difference [to us],” says Jones.

Adding up the job vacancies

Nevertheless, while the government may be confident that it has enough maths teachers and some in ITT are seeing demand, the frontline reality of schools looking to hire them makes for a different story, as data from SchoolDash makes clear.

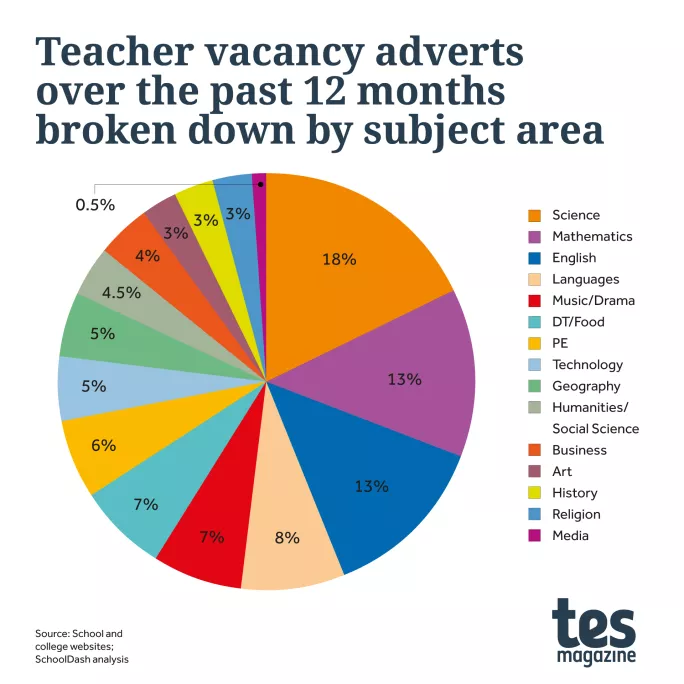

For example, when looking at data across the past 12 months, maths is the joint-second most advertised subject - along with English - underlining how much demand there is for these teachers. Yet English has seen an increase in its trainee target of a further 120 teachers.

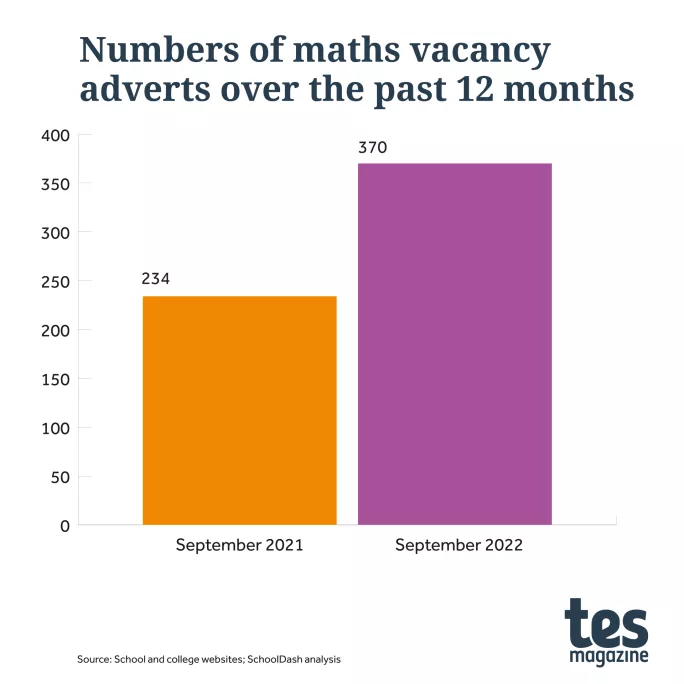

The DfE could again point to its rationale above for this, but perhaps harder to explain is that the SchoolDash data also shows there were 370 unfilled vacancies advertised in September 2022 - a point in the academic year when most schools should have a full component of staff, and before the start of the new recruitment window.

Furthermore, as the graph below shows, when we compare this year’s vacancies in September to last year, there has been a 58 per cent rise compared to 2021.

The situation is also clearly not improving, with October shaping up to be another busy month: already 201 vacancies have been posted.

Solving the recruitment equation

For frontline leaders, this data translates into very real and challenging recruitment problems on the ground.

Vic Goddard is co-principal of Passmores Academy in Harlow, Essex. He spoke to Tes earlier this year about the struggle to recruit, and when asked about the change in maths target numbers for ITT, expressed his dismay that there had been a drop.

“[There aren’t enough maths teachers] from our experience of the market,” he says. “There has been no change in the availability.”

The situation is so bad, says Goddard, that he has “zero expectations” when he puts out an advert, and “the retention of maths teachers remains [his] focus”.

What is really worrying, says Goddard, is the number of schools seeking maths teachers in the autumn term.

“To see vacancies in any subject in September is a major indication of there being something wrong,” he explains. “Our average has been four repeated adverts to get one application in maths, science and computer science.”

Marc Doyle, director of assurance and development at Consilium Academies, concurs with these concerns: “Recruiting the highest quality teachers in maths is a challenge for us and across the sector,” he tells Tes.

It is trying to tackle this by “making every effort to make up for the recruitment gaps we are experiencing by supporting as many mathematicians into the profession as we can.”

Another multi-academy trust (MAT) leader making similar efforts is Vince Green, at Summit Learning Trust.

Of the three secondary schools in his MAT, he says he is “lucky” to be fully staffed in maths at present but worries that, with the reduction in maths IT trainees, he can foresee problems if he has to go to market for a new member of staff.

“If there were fewer mathematics teachers in the pool, recruitment will become even more difficult for schools and colleges,” he explains. “As a trust, we would potentially need to be even more creative in terms of our approach to training and recruiting mathematics practitioners to ensure that we can maintain our high standard of delivery.”

Green’s point that we must maintain a “high standard of delivery” is something Worth worries about, too, noting that the target for maths ITT is based on maintaining current staffing levels, which he says is actually already backfilled by a number of non-specialists currently teaching maths.

“Twelve per cent of all secondary maths teaching hours in England are delivered by a teacher without a relevant post A-level qualification in the subject,” he says.

As such, even if the targets are hit and all appears well, the reality is that more than 10 per cent of teachers in maths classrooms are not dedicated maths specialists.

“There are likely to be some significant gaps in teaching quality within the current workforce,” he adds.

Finally, and perhaps confusingly, despite dropping the target for ITT maths recruitment, the DfE is making moves to entice more maths teachers by increasing the bursary offered to trainee maths teachers by £3,000, to £27,000, making it the highest financial remuneration available for ITT.

At the time, schools minister Jonathan Gullis said these “generous bursaries” would help shore up “the talent pipeline” for some of the hardest-to-recruit subjects.

Put this all together and it’s hard to work out exactly what the reality is for the sector’s maths teacher needs.

Until the DfE shows us its working out, it’s very hard to know what mark to give.

Gráinne Hallahan is senior analyst at Tes

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article