It now looks like we will - touch wood - get through the Omicron wave without national school closures.

While a relief for parents, who now live in fear of another round of homeschooling, the burden on schools has been considerable.

Not far off 10 per cent of staff were missing when term started last week, and there were 80 times more staff missing than brave ex-teachers who volunteered for the Department for Education’s hastily arranged returners scheme.

And hundreds of thousands of pupils were missing too.

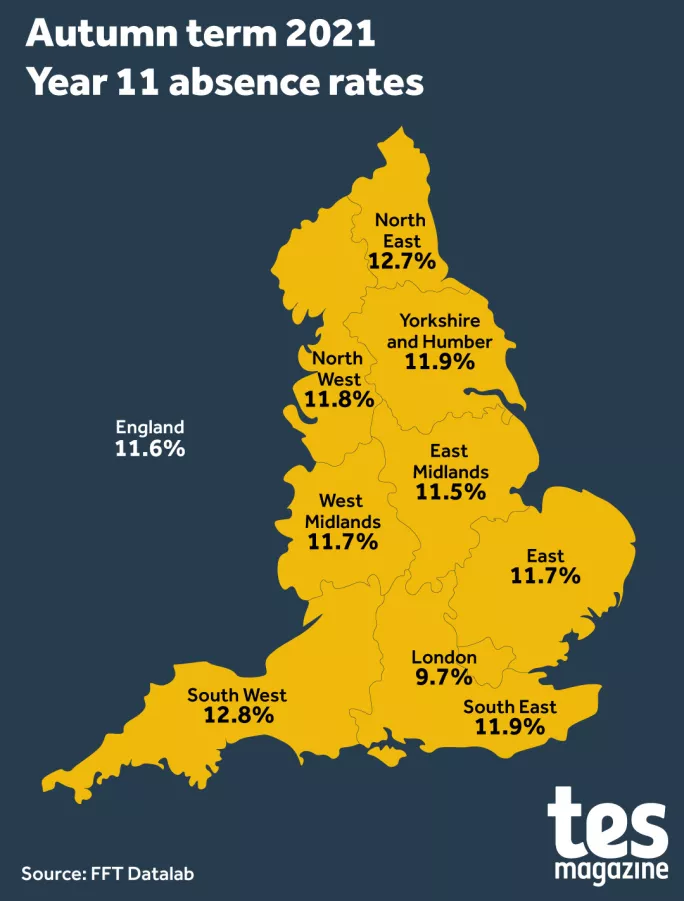

This is on top of an unsettled autumn term: figures released in the last few days showed Year 11s missed an average of 11.5 per cent of sessions last term, largely due to illness and isolation.

Sticking with exams

Given this, schools are, unsurprisingly, particularly worried about the exam years.

Students in Years 11 and 13 are in their third disrupted year of schooling with GCSEs and A levels just a few months away.

So far, education secretary Nadhim Zahawi is adamant that, barring further unknowns like a more dangerous new variant, proper externally assessed exams are going ahead this year.

Indeed, there is much regret in the DfE and No 10 at what is now seen as an over-hasty decision to cancel last year’s tests, causing long-term problems for the assessment system.

As such, it is surely the right decision to try and sit exams as normal this year.

The teacher assessment system last year was not just unfair but added a huge amount of workload to already exhausted staff.

More unfairness ahead

However, ministers and Ofqual may want to take this opportunity to rethink exactly how this year’s exams will work, given this further wave of disruption.

At the moment, Ofqual’s plan is to make the exam boards fix grades roughly halfway between last year’s inflated levels and results in 2019, the last time we had “normal” exams.

This will mean by far the biggest year-on-year drop in results we’ve ever seen, regardless of how students perform, particularly for A levels where the award of top grades almost doubled.

Moreover, this drop in grades will not be evenly distributed across centres.

Those that were more generous last year will see a bigger fall. At the same time, some schools and colleges have been more adversely affected by Covid than others - regional disparities alone for absence rates underline this.

There is no way to untangle these different distributional impacts. Inevitably centres that are the most negatively affected will prefer to blame the unfairness of the situation and the harshness of the government.

Ditch plans to tackle grade inflation this year

At the best of times, the media, the general public and even, if we’re honest, many school leaders, struggle to understand the complexities of assessment.

The chances that a narrative emerges that accurately reflects all these different moving parts is minimal at best.

Given this, if I were advising ministers, I would be strongly recommending that results be held at the same level as last year to reduce confusion as much as possible.

This would not remove distributional effects but it would significantly reduce the impact of any drops at centre level.

Ofqual did leave themselves the wiggle room to do this by saying they could change the grading plans if the circumstances changed.

If they’re going to make a change they will need to do so soon, before most universities make their offers to students, as admissions officers would have to adjust the numbers they hand out.

Act fast

If they go ahead with current plans the risk of another summer exam crisis feels substantial.

It may be that school leaders, and the wider public, are understanding of the disruption and are expecting drops this year, and the plan works.

But having witnessed first-hand how distributional changes caused uproar when new English GCSEs were introduced in 2012, I wouldn’t bank on that.

The other measures Ofqual put in place are sensible: students will be given additional information and choice in exams to acknowledge the disruption they’ve faced.

But this extra help won’t change the distribution of grades and that, ultimately, is what matters to student life chances.

If ministers want to avoid an August spent responding to footage of crying teenagers, they should ask Ofqual to reconsider - and fast.