- Home

- Analysis

- Specialist Sector

- Why the government must do more for international schools

Why the government must do more for international schools

After the trials and tribulations of the pandemic, it would be understandable if the international school sector had stood still and taken stock over the past 12 months.

Yet, as the latest Council of British International Schools (COBIS) annual survey reveals, the very opposite has happened, with British international schools continuing to grow and innovate during 2022 as they adapt to the new educational world that has sprung up.

Nowhere was this clearer than with 62 per cent of schools reporting increased pupil admission numbers - showing that the “flight to quality” that we saw in last year’s survey (where growth was reported by 51 per cent of schools) has only got stronger.

Innovation on the up

Talking to leaders across the sector, it seems a raft of factors are driving this - from a recognition that international schools offer high-quality teaching and learning, often with smaller class sizes, to the extracurricular activities international schools promote as part of a holistic educational offering.

We know too that a lot of this growth is coming from in-country families, rather than expats, continuing the trend that has grown up over the past decade as the emerging middle class seek the best school experience for their children as possible.

What’s more, the sector is clearly looking at further innovation and growth, with 25 per cent of respondents reporting that they are looking at how they could offer a full online offering of their school experience, no doubt buoyed by the positive experience many had adopting this way of learning and working during the pandemic.

Indeed, improved personalisation of learning and being able to use more platforms and resources to guide learning were two more positives that the report uncovered.

Wellbeing and academic concerns

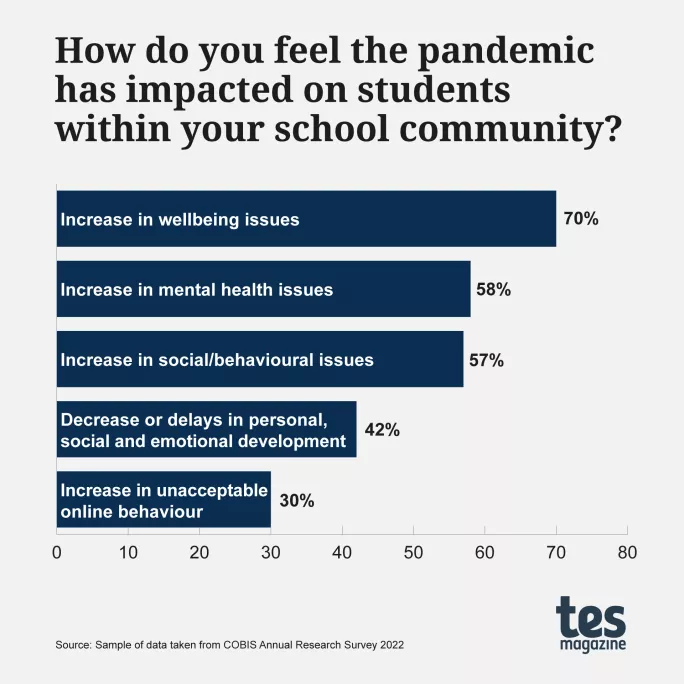

However, not everything schools reported was positive, with responses revealing that wellbeing and developmental issues remain a concern in both primary and secondary settings.

This is unsurprising when we consider the impact that the pandemic will have had on pupils of all ages - and it may even be the case that international schools are dealing with more pupils requiring support in part due to parents knowing they will get high-quality help, support and intervention at an international school.

In response, it is clear that many schools are taking this seriously, with many schools reporting for the first time this year that they have dedicated staff focused purely on wellbeing issues.

We are also seeing much of the same networking and information sharing that sprung up from the pandemic remain as a result of this, both organically and through in-person and online events hosted by COBIS, as those in the sector continue to share and learn from one another.

University challenges

Another area of concern - this time for the UK government - is that the number of pupils choosing a UK university for their onward destination was 44 per cent this year.

While this was an increase on last year’s 42 per cent, it is lower than in 2020 (50 per cent) and 2019 (53 per cent).

Clearly, policymakers need to take note of the reasons for this - which range from the cost of living to the cost of university courses themselves to the appeal of nations such as the USA, Netherlands and Switzerland as alternative destinations - to ensure this percentage does not fall any further.

The government should also look at how it can ensure it truly utilises the asset it has in the British international school sector and its esteem around the world.

It’s a flag of quality that should be flown as far and wide as possible - and yet sometimes there is a sense they do not appreciate it as much as they could and that there are opportunities to be seized and barriers to be broken down.

The accreditation issue

Not least - and this is an issue I’ve raised before - is the lack of formal recognition of alternative quality assurance schemes, such as the rigorous COBIS Patron’s Accreditation scheme, beyond the Department for Education’s British schools overseas (BSO) inspection framework.

Limiting it to just this means that many schools worldwide without BSO accreditation are unable to offer the Early Career Framework. A clear and surmountable barrier.

This, in turn, may put many new trainees off from working at certain schools, even if they are high achieving academically and regarded highly in their host country. It is an issue we will continue to raise.

Overall, though, our report makes it clear that, while pandemic-related issues around pupil wellbeing and academic development persist for British international schools, on a macro level the sector has weathered the pandemic and is looking to innovate to drive yet more growth.

With a deep commitment to school improvement and a clear purpose, our job now at COBIS is to ensure that we use these insights to hone our strategic direction for the years ahead and, with enormous positive energy, continue to help schools and students thrive.

Colin Bell is the chief executive of the Council of British International Schools

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles