- Home

- Analysis

- Specialist Sector

- The pandemic changed ITT, but is it for the better?

The pandemic changed ITT, but is it for the better?

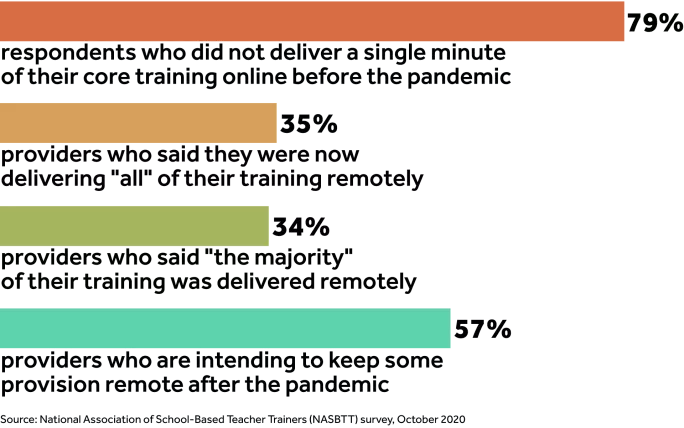

In October 2020, a survey of 141 initial teacher training (ITT) providers revealed that 79 per cent did not deliver any of their core training online before the pandemic.

However, just seven months into the pandemic, when the National Association of School-Based Teacher Trainers (NASBTT) conducted this survey, 35 per cent of providers said they were now delivering “all” of their training remotely and 34 per cent said “the majority” was delivered remotely.

“Our members tell us that they learned a lot through the pandemic,” says Emma Hollis, executive director of NASBTT.

For higher education institutions (HEIs), the shift to online teaching was equally rapid and Professor Samantha Twiselton, director of Sheffield Institute of Education at Sheffield Hallam University, says it led to a huge shift in perspective.

“I think we all found that, actually, the taught content can be delivered pretty effectively online,” she tells Tes.

This ranged from modelling teaching remotely to trainees and arranging for them to teach small online lessons, to asking trainees to plan lessons that considered how they could be delivered in person or online and running mentor sessions online, too.

And then the new delivery method began to have a wider impact on what was being taught, too.

An Ofsted report in May 2021, which looked at how ITT providers had adapted to the pandemic, explained that “while Covid-19 has been an immense challenge for partnerships and their trainees, the move to remote training and remote teaching has, in some cases, stimulated deeper and more connected thinking about the initial teacher education curriculum”.

So, what was once thought impossible has now not just proved possible but perhaps preferable in some areas. This raises the question of how far things will - or should - return to “normal” now Covid restrictions have lifted.

How ITT providers adapted to remote provision over the pandemic

Twiselton and Hollis believe the innovation and experimentation of the past two years are here to stay.

“In the future, where possible, we will want to keep a bit of a blend… because it’s so much more effective for tutors and for trainees,” says Twisleton.

Hollis concurs. There are aspects of online delivery, she says “that proved to be much more efficient to do remotely and they [providers] will continue to do [that] remotely”.

The 2020 survey backs this up, with 57 per cent of providers intending, at that point, to keep some provision remote after the pandemic.

But in many ways, blended provision will be as much of a challenge to define and roll out as online-only provision. And with the ITT re-accreditation underway, choices about delivery are going to be crucial. So, is there a consensus emerging about the best way forward?

Hollis says she believes there will be elements of “online” courses that most, if not all, providers will maintain.

Post-pandemic innovations

For example, asking trainees to pre-record themselves delivering a lesson. This enables the trainee to focus solely on their delivery, explaining a key concept and the resources they would use that could then be critiqued, rather than the multiple other factors a teacher may have to consider in a live situation, such as behaviour or pastoral management.

While Hollis acknowledges that aspects such as behaviour management go hand in hand with lesson delivery, she argues that, as part of a training programme, being able to “strip away” those issues, “home in on the quality of explanations” and explain “things in a very clear and concise way” have real benefits to trainees.

Another example where new adaptations have proved successful and that may remain post-pandemic is the ability for key stage 1 teachers to practise the correct sounds for phonics and be assessed on it.

“When schools were operating bubble systems and teachers couldn’t cross between bubbles, it became very difficult to go and observe the teaching of phonics,” says Hollis.

This was an issue that Ofsted noted in its report, too, saying that “many primary trainees did not have as many opportunities to teach early reading, including systematic synthetic phonics in key stage 1”.

Even pre-pandemic, Hollis says expert feedback on phonics required a lot of planning.

But having trainees deliver the phonics teaching online gets over the logistical challenges and ensures that every trainee gets the best possible feedback, she argues: “It allows somebody with expert levels of systematic synthetic phonics to view all of the trainees and give feedback whereas, in the past, they might have needed to have to travel to multiple schools to do that, which, obviously, is logistically much more complicated.”

Katrin Sredzki-Seamer, director of the National Modern Languages School Centred Initial Teacher Training (SCITT), offers another example. She says hosting lectures online means they could be recorded so trainees could listen to a key point again or, if anyone misses it live, it’s available whenever required. She adds that it can also make it easier for trainers to check understanding among trainees.

“You wouldn’t be able to necessarily see everyone’s answers in a room but on Zoom, you can [use polls and chat questions] to save and evaluate later.”

Twiselton agrees and says online lectures can help make life easier for trainees from a practical point of view, too: “[Trainees] often complained before Covid about timetables that sometimes would be quite messy in terms of having to come in for just one session.” So hosting that session remotely “may make more sense now”.

Sredzki-Seamer adds that with people now comfortable being taught online, a wider array of expert speakers is available for current trainees - and they can reach a far greater audience.

“I can invite multiple cohorts, previous trainees and mentors to attend, so it gives you multiple opportunities to make more out of an expert speaker you have,” she says.

Reaching the masses

Hollis says NASBTT has seen this, too, in terms of how it delivers events - something pre-pandemic, she admits, she was not convinced would work.

“We’d been talking for a long time about taking our events online and I was reticent to do that because I didn’t think the members would want that,” she says.

However, after shifting to this delivery during the pandemic, NASBTT is now hosting subject-expert speaker events attended by 10,000 people - something that would never be possible pre-pandemic.

“We couldn’t have run face-to-face events that would have been suitable for trainees simply because of location, [but] we’re now at a point where they’re quite reluctant to let go of online [events].

“They want us to keep things online because of all the savings in terms of cost and travel and time,” she says.

This benefit was noted in Ofsted’s report: “Visiting speakers have been easier to attract because there is no travel time, meaning that more partnerships have the opportunity to learn from those with specific expertise.”

Not only this but Claire Harnden, deputy chief executive of the South Farnham Educational Trust (SFET) and director of SFET Teaching School Hub and SCITT, says running these sessions online can often be more efficient for trainees and saves money.

“We had a big question here about how much of our professional studies were structured around the day - what time they arrive, when do we stop for a break, then for lunch, then thinking, ‘well we’ve got the venue so we may as well keep them for the afternoon’,” she notes.

“With online learning, it challenges you to think about how you deliver sessions, what is really important and how it is best delivered - is it in person, or is it through a school-based task or professional development task that the trainee can complete in school with guidance.”

Given all this, she says, they are definitely planning on keeping a “blended learning approach” for its 170 trainees this year and into next year, too.

Benefits to mentors

It’s not just trainees who benefit from all this. For school-based mentors working with trainees, switching to remote working over the pandemic has had many benefits, as Sredzki-Seamer outlines.

“For our mentors, we run some of our training online and that’s actually made it easier for some of them to attend because they can’t always get out of school,” she says.

Similarly, positive views on remote mentoring are held by Hollis, who says SCITTs have seen attendance and engagement with mentor training increase, as sessions can be accessed on demand for those that missed them, and it reduces the time and hassle of attending sessions.

“The vast majority of providers, if not all of them, will keep the majority of their mentor training online,” she says.

Several school-based mentors told Tes that they hope this will be the case.

“It is a great, time-efficient way to deliver training that takes into account the busy working lives of mentors and the difficult balance of ‘fitting it all in’,” says mentor Charlotte Tighe.

Another, Ollie Witchell, explains: “I have found the mentor training remotely highly beneficial and easier. Covid has allowed our profession to use more technology to our advantage, enabling us to reduce travel time and use our time more effectively.”

Will examples like these tip the balance for provision to be more online than offline? Hollis doesn’t think so.

“The process of learning to be a teacher is a physical one. You need to be in the classroom,” she says.

The limitations of remote learning?

Indeed, Sredzki-Seamer and Harnden say the return of face-to-face teaching for delivery of ITT courses is something almost all trainees have welcomed, and that means there is a point at which remote ITT can only go so far.

“We have found people have really missed the face-to-face elements, the opportunities before a session over coffee to be able to speak to one of our staff and pastoral support team, or just each other, to share those experiences in that informal way,” says Harnden.

It’s a sentiment Sredzki-Seamer shares: “They really hated the bit where we had no face to face at all and they were absolutely delighted when we were starting to be able to be back, even with masks and social distancing. It’s reassured me that the face-to-face element still needs to be there.”

And it’s not just the social side. Twiselton says that, for all the innovation brought about by the pandemic, there are certain elements of teacher training that need to take place in person.

“There’s a big practical element to teacher training and, for more practical subjects - such as science - you need to be there on campus, so I think that will remain.”

Hollis concurs: “In secondary science, for example, [trainers] are modelling experiments, or in primary art, they’ll be modelling what it means to get the clay out and actually work with the children creating sculpture, so there’s an awful lot that is quite difficult to translate online.”

Looking to the future

While not contesting these views directly, there are those in the ITT market who believe training can be more dramatically shaken up than the examples given.

Since September 2020, the National Institute of Teaching & Education’ (NITE) at Coventry University has offered an ITT course that delivers all of the taught content remotely via online platforms to trainees situated anywhere in the country, meaning there are very few times across the course when the trainee needs to attend the university itself.

The course was started because Professor Geraint Jones, executive director and associate pro-vice-chancellor at NITE, believed there was scope to “offer a different way to attract new teachers to the profession” who may otherwise have been unable to do so.

All the professional study element of the course takes place remotely, via video lectures, webinars and catch-up with academic staff. The rest of the time - usually four days a week, although sometimes five, or if on a part-time option, just two days - trainees are in schools. Overall, trainees are only actually required at the university four times in any academic year.

To make this work across the country, rather than partnering with the same schools each year for placements, the university proactively finds schools near to trainees, depending on their location.

Jones says to do this, the university undertakes a “rigorous assessment process” of the school in the locale of the trainee to ensure they have the “capacity, experience and expertise” to deliver the school-based training programme students are following.

“There’s a lot of work going on prior to the training starting to see that the school has that capacity to be part of our programme,” adds Jones.

Rising demand

Early indications are that his hunch that this would broaden ITT appeal was correct, with 500 trainees applying for the 2020 cohort - and 121 offered places. There were more than 1,500 applications for the second year, leading to 357 offers. The trajectory is clear: “We will likely be training around 1,000 ITT trainees per year by 2023-24,” says Jones.

For him, the fact that trainees spend so much of their time in school implementing what they are learning in their lessons negates concerns raised earlier around the fact that trainees won’t have hands-on practical training sessions with their providers.

“Trainees have access in their schools to everything that they practically require,” he says.

“[They] acquire knowledge online, reflect and discuss with their mentors, observe modelling in their schools, practise in their schools, and receive feedback and goals to improve. This sequence matters most and is more important than bringing people together to one location to learn.”

He says this model not only supports the trainees but is appreciated by schools, too, as it opens up a pipeline to new potential hires.

“More schools are seeing the recruitment of teachers as a priority and, where they can involve themselves in either growing their own staff or be part of something like our course, that gives them the chance of accessing more trainee teachers. That’s really beneficial,” he says.

“It doesn’t stop them from partnering with their local providers but it means they are getting more people interested in training or working in their schools.”

An additional way in which he says this online model works particularly well is that it does not have to adhere to the traditional academic calendar of starting in September but can instead start at several points in the year.

For example, in 2021, cohorts started their courses in January, February, April, July and September, and this is something he also says can be key to enticing new teachers.

“If someone, say, is changing their career and they’re out of work, and that happens in October, they can’t really wait until the following September to start training, [but what] we’re able to do is offer those multiple start dates in the year,” he says.

An added bonus, says Jones, is that, in theory at least, there are no ITT cold spots, where there are no options for people to engage with ITT owing to lack of provision. Jones argues that this could help broaden access to teaching for those who may otherwise be unable to move to study.

“For people in hard-to-recruit areas of the country, you are offering a model that can work for them and it means we are attracting people to the profession who may not have otherwise been able to [study],” he says.

A life-changing opportunity

This is exactly what trainee Fiona Brittan, who is based in Cumbria, says made the course viable for her when she was looking to train to be a teacher while continuing her current role as a teaching assistant.

“I’d been trying to become a teacher for years [but] every course I found involved me giving up work to become a student full-time or move to university and give up the job I love. So, for a long time, I just thought, ‘this is madness, I’ll stay as a TA’.”

However, with the Coventry course, she is able to stay working in her job and attend the session remotely - such as a weekly tutoring meeting on a Monday at 6:30pm - and is on track to qualify in July.

It’s a similar story for Kevin Lawrence, a teacher studying for his PGCE while working full-time at a special school in Lytham St Annes, who is in the final stages of gaining his teaching degree while he works.

“This has given me an opportunity that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise, to take the next step of my career,” he explains.

Prior to this, any option he investigated involved having to leave his job and move away - neither of which he wanted to do.

This does mean Lawrence has to study on top of his full-time job - mostly in the evenings - which he says can be tough but the flexibility is key.

Additionally, the fact that the course was proactively designed to be delivered remotely was a selling point: “I was quite hesitant to do something that wasn’t designed for distance because, if another lockdown happened, I didn’t think that support would be in place.”

This proved prescient when, in December, Lawrence caught Covid. But because the course was designed to be run remotely, he was able to continue it without interruption.

“I didn’t feel unwell, I just had to isolate, but I was still able to attend my lectures, to work remotely, do my lesson planning and send it into school, so that was a real positive.”

Confidence to overcome challenges

None of this is to suggest that there aren’t hurdles in running this sort of course. The main one that Jones acknowledges is finding partner schools: “Our biggest challenge is finding schools to place [students] in - that’s really our only restrictive element.”

However, as more schools link up with the course, it should, in the future, broaden the scope of settings it can use as and when new trainees can sign-up in different parts of the country.

What about the fact that working this way means that face-to-face engagement with trainers and other trainees is lost?

For Brittan, this has not really been an issue: “We’ve got a really good WhatsApp group going on, where we moan and groan about everything together,” she says, adding: “But it’s slightly odd that we’ll probably never actually meet.”

Meanwhile, Lawrence says he talks to his tutor “probably four or five times a week as a regular back and forth”, to ensure the work is being engaged with and completed as required.

“Our lecturers are always in contact and supporting us through to make sure we are keeping up, and not falling behind and getting stressed.”

However, other ITT providers highlight some potential dangers of the approach.

Sredzki-Seamer says she would worry if too much of ITT courses were remote, as it would require more supervision of trainees to ensure they didn’t slip behind.

“If you don’t have a catch-up every now and then face to face, and hear what they say, you could miss those who might be trailing off and not making as much progress as you would like, especially if the [school] mentor is kind and doesn’t necessarily share all the information because they don’t want to drop their trainee in it.”

Despite the reservations, Jones’ point about bringing new people into the profession that would not have been able to access it otherwise is an important one, however, ITT providers try to do it.

Reaching new teachers

For many years, the overall trend for ITT take-up has been to fall short of the overall targets being set by the government - with the latest data revealing the perilous state of teacher recruitment.

Some of this decline is because of the huge boost the pandemic gave to ITT numbers in 2020 and 2021. But it underlines that the sector is still struggling to entice enough teachers to the market.

So, could a model such as NITE’s spread and help broaden the ability for more individuals to consider training to become teachers and potentially tackle the shortfall?

Economist Jack Worth, from the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER), says moving to offer more remote courses would ensure ITT kept pace with “trends in the wider workforce, where many more jobs are being advertised as remote-only” and could be especially appealing to career changers.

The benefit of remote learning for ITT trainees was also cited by Ofsted’s report last year, when it noted the switch to online learning had improved “equality of access to the ITE curriculum” by allowing many trainees to “keep learning despite having additional caring commitments, such as childcare”.

Given that this has all happened during a major market review of ITT providers, could this be something the government looks to build on to help tackle the teacher shortage?

If it is, the government is keeping quiet about it with no reference to this model in its 70-page response to the ITT market review report, published in December.

However, Twiselton, who has been on the government’s steering group of the ITT market review, admits that more focus is needed because there has been little “pressure or incentive” for providers to deliver other types of courses.

“If you’re recruiting enough people and you’re managing to keep your courses running, it’s easier to just default to what you know, but that means you are just tapping into the same kind of people that you always tapped into,” she says.

Furthermore, she says the pandemic and the market review offer a perfect opportunity for the ITT sector to think about how it can support other people who want to train to be teachers, not least by making courses more flexible for part-time training.

“Schools need to be good at helping people who want to work part-time but we need to think about this for initial teacher training as well.”

Hollis agrees that SCITTs, too, need to think about this as, currently, options for part-time study are few and far between.

“There are part-time programmes but they’re not particularly common, they’re not particularly easy to find and they’re not very well geographically spread,” she says.

Remote ITT, she says “has the potential to support that part-time approach, so it could be that you find a local school that you go to a couple of days a week but, because you don’t have to travel very far, you can do your online learning in your own time around another paid job, for example”.

Innovation begets innovation

As such, Twiselton says she hopes the DfE might step in over the market review to help encourage providers to think about new models, and get them up and running.

“To be honest, I wish DfE were pushing providers to think about this because I do feel like there’s untapped potential in terms of people who could make really good teachers but for whom, at the moment, it just feels like a step too far because of the full-time commitment.”

Everybody is having to rethink their courses “from scratch” she says, “so if the DfE found levers to get more [ITT providers] doing this, that would be good”.

Tes asked the DfE if it was considering this within the market review but it declined to comment.

However, as cited earlier, Ofsted has noted the benefits that a mix of online and in-person training can bring to ITT - especially around training for mentors - and the ITT market response does at least allude several times to wanting providers to think flexibility about their courses.

And perhaps this is the key point. Where that suggestion may have fallen on deaf ears in the past, the pandemic has shown providers how they can be flexible and use technology to harness the best of remote teaching within ITT courses for the benefit of trainees and mentors.

So, as innovation in this space continues to mature from the learnings of the past two years, it could well be the case that those involved in the vital business of teacher training continue to evolve in a manner that suits the needs of their cohorts best.

“I would say it’s probably the most rapid and successful change I’ve seen in education for a very long time,” concludes Harnden.

Dan Worth is senior editor at Tes

You need a Tes subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

Already a subscriber? Log in

You need a subscription to read this article

Subscribe now to read this article and get other subscriber-only content, including:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters

topics in this article