- Home

- Are your naughty pupils predestined to be anti-social?

Are your naughty pupils predestined to be anti-social?

Children who behave badly at a young age should be shown more compassion by their teachers, new research suggests.

A blanket policy on “heavy-handed” punishments, such as exclusions, is not necessarily the most effective approach for tackling bad behaviour in the long term - as people persistently acting in an anti-social manner may require greater support at an early age, according to an expert in educational psychology.

Christina Carlisi, from University College London, co-authored the research published today in the Lancet Psychiatry Journal, which discusses patterns in anti-social behaviour and how they might relate to brain structure.

Related: Use more praise than punishment, study tells teachers

Behaviour: Are we putting the pupils’ needs first?

Advice: Six tips for improving behaviour in school

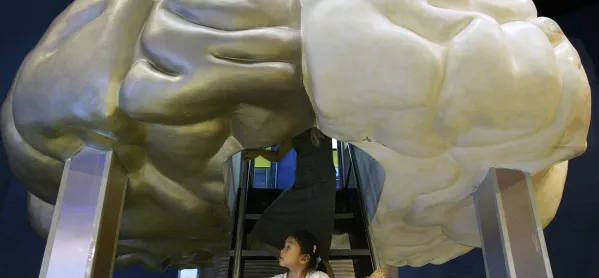

The article suggests that the brains of people who engage in lifelong anti-social behaviour may be smaller and structured differently to other people’s brains.

“From a school’s perspective, our study showed that there’s a select group of individuals who display persistent patterns of anti-social behaviour, that typically arise relatively early on in childhood and that persist right through into adulthood,” Dr Carlisi said.

Behaviour support

“A lot of these kids are often written off quite early - they’re just classed as the ‘naughty kids’, and they’re rarely given the support that they need.

“So I think what our study speaks to, from that regard, is the idea that it’s good to have a little bit of compassion for these individuals...and focus our resources on this group of individuals who are in need of a little bit of extra support.”

She added: “From the teacher’s point of view, having an awareness of what that challenging behaviour looks like, and being able to identify that and react to that in a way that is supportive and consistent - rather than just saying: ‘Well that is a naughty kid, we’ll put them in time out or detention’ - [is useful].

“That is to say, rather than only punishing bad behaviour and never rewarding good behaviour, both aspects of behaviour should be responded to and supported - with similar (ie, consistent) consequences each time the behaviour occurs. ”

Dr Carlisi said that, while “there is a place for exclusions and we live in a society in which actions have consequences”, teachers should avoid excluding children “right off the bat...with no chance of reform”.

“Heavy-handed approaches might not necessarily be the most effective in the long term,” she added.

“Our research shows that blanket policies are often not helpful as there is heterogeneity among anti-social individuals. An awareness of, and subsequent support structure for, those individuals whose behaviour might follow a different pattern (eg, arise very early in life) would be very helpful.”

Dr Carlisi said this “also has implications at a more structural level”, in terms of the support that is needed in schools and health services.

“If we can identify people early on, and give them the support that they need, then perhaps that would mitigate some of the problems later on,” she said.

“So it’s not saying that anyone who displays anti-social behaviour as a child is destined to do that for the rest of their lives. It’s more about saying that there is this group of individuals that do develop this behaviour earlier, and that they might be the ones that are in need of that little bit of extra support.”

Dr Carlisi acknowledged that the study had some limitations as, while behaviours were assessed throughout childhood and into early adulthood, brain scans were not taken until the subjects were 45 years old.

“So we don’t know whether they looked different at a brain level from birth or from early childhood, and that has given rise to the behaviours, or...that a persistently anti-social lifestyle, which is often co-occuring with things like prolonged substance abuse and mental health problems, has shaped the brain development across the lifespan,” she said.

“But what we did show is that, based on these repeated assessments of anti-social behaviour across the lifespan, those individuals who had the earlier onset childhood anti-social behaviour that continued across the lifespan were uniquely characterised by reduced brain structure in certain regions.”

In the study, researchers from the UK, US and New Zealand analysed the brain structures of 672 adults aged 45.

Eighty had lifelong anti-social behaviour, 151 had shown anti-social behaviour only in adolescence and the remainder, 441, had no history of persistent anti-social behaviour.

The first group had a smaller mean corticol surface area and lower mean corticol thickness - which indicate grey matter size - than those who had never engaged in anti-social behaviour.

And the group had reduced surface area in 282 of 360 brain regions, and a thinner cortex in 11, most of which play a part in goal-directed behaviour, regulating emotions and motivation.

Keep reading for just £1 per month

You've reached your limit of free articles this month. Subscribe for £1 per month for three months and get:

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Award-winning email newsletters