- Home

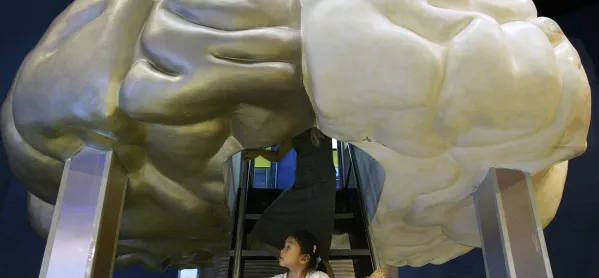

- Behaviour management: it’s all about the brain

Behaviour management: it’s all about the brain

It’s only the second lesson of the day and Connor is hiding under the table again. What do you do? Do you ask him what’s wrong? Try to reason with him? Offer him a reward if he comes out?

The answer is none of these things. Connor’s brain is not in position to engage with these solutions; he is experiencing a fight-or-flight response that cannot be overridden by appeals to logic.

But speaking last week at the 2018 IPEN Festival of Positive Education in Fort Worth, Texas, former school counsellor Lyndsay Morris explained how learning about the brain can help teachers to better understand how to help pupils like Connor.

It all starts with understanding how our brains process stress, she says.

Drawing on a model developed by Dr Dan Siegel, clinical professor of psychiatry at the UCLA School of Medicine, Morris explained that we can think of the brain as being like a house, with three distinct floors that are connected to each other.

At the bottom, you have the “basement brain”. This is the part of the brain that controls basic functions such as breathing, blood pressure and heart beat.

“This is the part of the brain that makes you pull back immediately when you touch a hot stove, without you having to stop think and think about it. It is the oldest part of your brain, your reptilian brain,” says Morris.

Next, comes the “downstairs brain”, where the amygdala is located. This is your “emotional brain”.

“The amygdala is always scanning the world for what’s wrong. When the amygdala senses danger - which thousands of years ago was that a lion was going to eat you, whereas now in middle school might be seeing two people whispering and wondering if they are whispering about you - you go into fight, flight or freeze.”

Finally, we have the “upstairs brain”, including the pre-frontal cortex. This is the part of the brain responsible for executive function, which allows us to reason and to think logically

“It’s the reason why in meetings, we can think, ‘hmm, I might not say that or I could get fired’, or ‘I won’t have any friends left if I say that’,” says Morris.

Behaviour management tools

But what does this have to do with Connor under the table?

Well, Morris says, if pupils do not have the skills to regulate their responses to high-pressure situations - sitting an exam, or having an argument with a friend, for example - their brain will experience the stress of this event as a threat, causing their emotional brain to completely take over, while shutting down their ability to reason.

To counteract this, teachers must help students to re-establish the missing connections between the different parts of their brain.

As for how to do this, Morris says that “when a student is triggered by a stressful event and their amygdala is firing off, the first step is to [help them] regulate.”

This means going back to the basement brain and focusing on the basic functions: regulating the breathing and performing physical movements.

After that, the next step is to “relate”, tapping into the student’s emotional downstairs brain by connecting with them and acknowledging the feelings they are experiencing.

Only then can you appeal to the student’s sense of reason and ask the logical questions, such as “What happened?”, “How do we fix this?” and “Why are you hiding under that table?”

However, a lot of the time, this is the step that teachers start with.

“In a lot of schools, we start with reason,” Morris says.”We are starting with reason when there is no connection and [the child] can’t access the pre-frontal cortex at that time. This is why ‘think sheets’ should never be a first intervention. The first intervention should be breathing, movement, connection, and then getting to the ‘what happened?’”

Instead of waiting until a child is hiding under a table and then trying to talk them through breathing exercises, Morris suggests taking a preventative approach. She recommends teaching children about how their brains work and then creating areas within your classroom where children can go to self-regulate.

By setting up a “green room” space at the back of the classroom and allowing children to visit this area to perform movement or breathing exercises when they are feeling overwhelmed, teachers can help them to take back control.

And, Morris argues, if you help children to understand their own brains better, then this is even better still.

“Teaching kindergarteners about their brain so [they can say], ‘Miss Morris, I’m about to flip my lid, I need to go to the back of the classroom and do some breathing’ - that’s empowering,” she says.

Register with Tes and you can read two free articles every month plus you'll have access to our range of award-winning newsletters.

Keep reading with our special offer!

You’ve reached your limit of free articles this month.

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles

- Unlimited access to all Tes magazine content

- Save your favourite articles and gift them to your colleagues

- Exclusive subscriber-only stories

- Over 200,000 archived articles